Richard Wright escaped poverty and the South by taking the northbound to Chicago in 1927. He wrote about it his semi-autobiographical, Black Boy.

A Catholic had loaned Wright his library card, which Wright used to read H. L. Mencken essays and other leading writers of the 1920s.

His reading gave him “vague glimpses of life’s possibilities.”

“Rosary Ntz.” That’s what Baltimore’s violent junkie turned do-gooder Rafael Alvarez keeps on the radiator where he says his Rosary. It’s a notebook where he writes down what comes to him during the meditation.

“Wait!” I thought when I read that, “You can do that? That’s legal? You can stop mid-chain and jot down thoughts?”

It passed approval with the editorial lights of The Lamp, so I guess it’s okay. I’m gonna start doing that. In fact, I’ve already started, using my commonplace book.

Richard Wright taking the northbound. Me jotting down Rosary notes.

Two doors opened by reading.

“I wish it need not have happened in my time,” said Frodo.

Few things are more degrading than being a child of the modern age.

“Prison wife” comes closest.

Its not our fault that we were born into modernity, but we can emancipate ourselves from it.

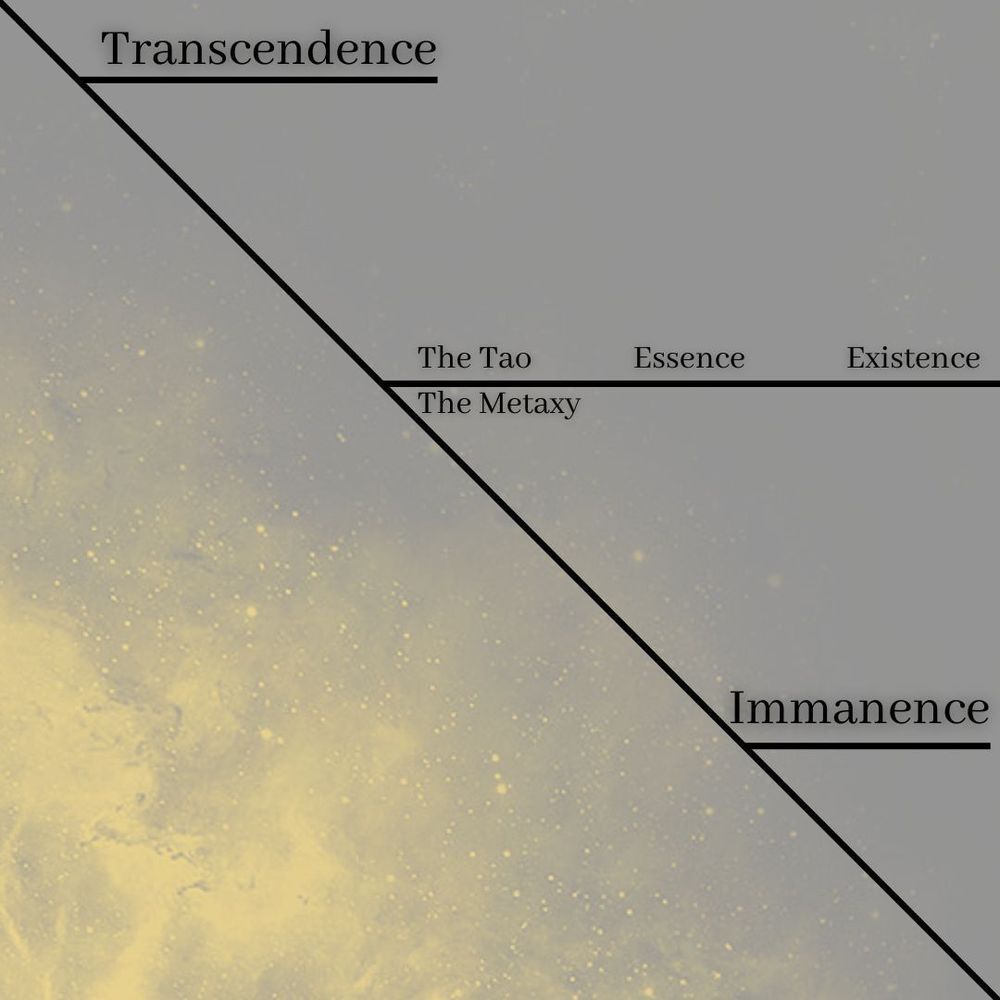

Modernity is the Great Rejection: the rejection of the Tao. So we were born into an era that rejects the Tao. Therefore, anything we can do to contact the Tao is an act of emancipation.

And things like meditation and prayer are practically acts of existential rebellion.

But there are many other means of emancipation. Some good; some bad.

We can Borden ourselves to emancipation. You remember Lizzy Borden:

Lizzie Borden took an axe,

And gave her mother forty whacks.

When she saw what she had done,

She gave her father forty-one.

We can take this approach to emancipation: going off the grid or hitting the road, doing drugs, looking for kicks in a non-stop quest to escape modernity.

Or we can try something less vigorous.

Like reading.

Patient reading without purpose is meditative. We read, something strikes us, we look up and think, then we read some more.

I’m not even sure the content is important. It’s the medium itself: our interaction with the printed page.

“Even Harlequin novels, Scheske!?”

I guess, though I’ve never benighted myself with one, so I can’t say for sure, but before you pursue porn prose, try writers who stand outside modernity: either by happenstance of time (Seneca) or in their style (anyone before Hemingway), ideas (Iain McGilchrist), temperament (Henry Adams), or disposition (Russell Kirk).

You then get the double whammy: absorbing non-modern beverages (the writers) through a non-modern straw (reading).

“One of the inadequately recognized functions of literature is to show how reality always eludes too firmly drawn ideas.” Joseph Epstein

Also, I wouldn’t dismiss good fiction.

Fiction, even modern fiction, is a stance against modernity.

Modernity wants us to believe we can use logic and purpose to determine our course of action.

That’s not true. Things are never clear. Things are never logical. Things always escape our willful grasp.

It’s because there’s more to reality than we can perceive, much less understand or control.

Fiction is a window to that greater reality.

“The novel’s spirit is the spirit of complexity. The novelist says to the reader: things are not as simple as you think.” Milan Kundera