Essay Excerpt

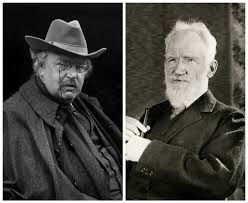

Chesterton and Shaw

Atheist/Christian. Aquabib/wine drinker. Thin/fat. Vegetarian/meat eater. Socialist/Distributist.

Shaw/Chesterton. They fought it out in print, they fought it out verbally.

It would've been great to see those debates. But what made them so good? Chesterton's early biographer, Maisie Ward, explains it better than anyone. She starts by pointing out that Shaw was asking the questions that infuriated the British conventional class, but so did Chesterton:

They hated Shaw's questions before they began to hate his answers. And that is probably why so many linked Chesterton with Shaw -- he gave different answers, but he was asking man of the same questions. He questioned everything as Shaw did -- only he pushed his questions further: they were deeper and more searching. Shaw would not accept the old Scriptural orthodoxy; G.K. refused to accept the new Agnostic orthodoxy; neither man would accept he orthodoxy of the scientists . . .

They attacked first by the mere process of asking questions; and the world thus questioned grew uneasy and seemed to care curiously little for the fact that the two questioners were answering their old questions in an opposite fashion. Where Shaw said: 'Give up pretending you believe in God, for you don't,' Chesterton said: “Rediscover the reasons for believing or else our race is lost.' Where Shaw said: 'Abolish private property which has produced this ghastly poverty,' Chesterton said: 'Abolish ghastly poverty by restoring property.'

And the audience said: 'These two men in strange paradoxes seem to us to be saying the same thing, if indeed they are saying anything at all.' . . .

Shaw and Chesterton were themselves deeply concerned about the answers. Both sincere, both dealing with realities, they were prepared to accept each other's sincerity and to fight the matter out, if need were, endlessly.