Why was the "Door" Concept Such a Big Thing in the 1960s?

Tao Teh Ching, Chapter 1

Answer: For the same reason it should be a big thing in the 2020s

We see better in the dark.

In the light, we see everything, and it's everything that blocks Everything. It's a "forest for the trees" thing.

Picture yourself as an archer. The target, taking aim, you're locked in: everything around you shut out as you focus.

It's a beautiful manifestation of the left hemisphere of your brain in action.

Now picture yourself as an archer every moment of the day. A parade of targets, always taking aim, always locked in . . . Everything around you shut out as you focus.

It's an ugly manifestation of the left hemisphere gone rogue.

If you don't want to live that ugliness, shut off the lights.

Darkness within darkness.

The gateway to all understanding.

There are 300+ English translations of the Tao Teh Ching. The translations vary wildly, sometimes making the reader wonder if he's reading the same book.

But the handful I've read all conclude the first chapter with reference to a "door," "gateway," or other portal.

The "door" concept drove a large part of the 1960s counter-culture.

Aldous Huxley wrote about his mescalin experience:

For the moment that interfering neurotic who, in waking hours, tries to run the show, was blessedly out of the way.

"That interfering neurotic," Huxley makes clear, is all of us in modern Western culture.

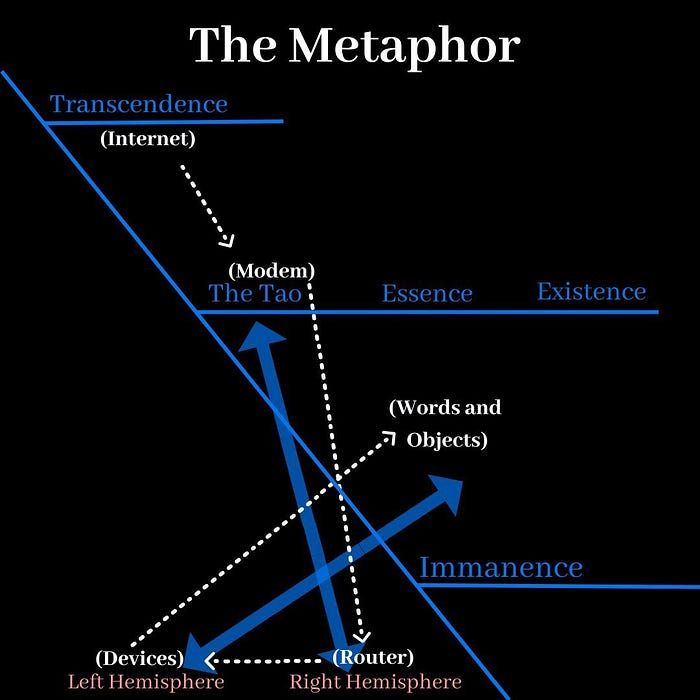

The neurotic runs back and forth in the Subject-Object Tunnel or, to put it more precisely, the Left Hemisphere-Words and Objects Tunnel.

It's the Tunnel illustrated by the thick blue "horizontalish" (45-degree) arrow in The Metaphor diagram:

Huxley's "neurotic" thrives in the Tunnel and it's the Tunnel that keeps him neurotic. That's why the arrow above points in both directions.

But when mescalin took Huxley's neurotic (his every-day self) out of the way?

He could leave the Tunnel.

He could open a door (illustrated by the light blue square where the two thick arrow lines cross).

The Door to the Highway

Huxley implied that the neurotic was "Martha" in the Gospel story and Mescalin allowed him to take a door to Mary instead . . . and shut the door on Martha (Harper Perennial Modern Classics, 2009, p. 41).

Following Huxley, it might be appropriate to simplify the name of the Tunnel. Instead of the "Left Hemisphere-Words and Objects Tunnel," we can merely call it the "Martha Tunnel."

The "verticalish" (80-degree) thick blue line would, again taking Huxley's cue, become the "Mary Highway."

The Mary Highway runs to the Tao.

It's no coincidence that Chinese translations of the Gospel of John begin, "In the beginning was the Tao."

We Need to Go Along the Tunnel and the Highway

I picture the Martha Tunnel as one of those brightly-lit multi-lane freeways, like the kind I drive through in the Allegheny Mountains to visit my son in South Carolina.

They're efficient: minimal swerving, no switch-backs, no heightened risk of molestation by deranged hillbillies near the river. They're fast: 65 mph, if not 70. I reach my target faster. I accomplish my goal.

It's great. I get to spend more time with my son because I spend less time driving up and down mountains, getting caught in sleepy burgs, bumping down dirt roads that lead nowhere.

But I miss so much: the ups and downs of mountains, those sleepy burgs. the dirt roads.

Those tunnels under the Alleghanies are so bright. I see everything.

But I simultaneously miss everything.

So it is with the Martha Tunnel versus the Mary Highway.

We need the Tunnel and the Highway.

We need the left hemisphere and the right hemisphere.

We need light and darkness.

Unfortunately, modern living is all Tunnel, all light, all Martha . . . all left hemisphere.

And we're missing Everything.