Hypocrite, Me: Netflixing My Own Aesthetic Prison

Aaron Timms at The New Republic

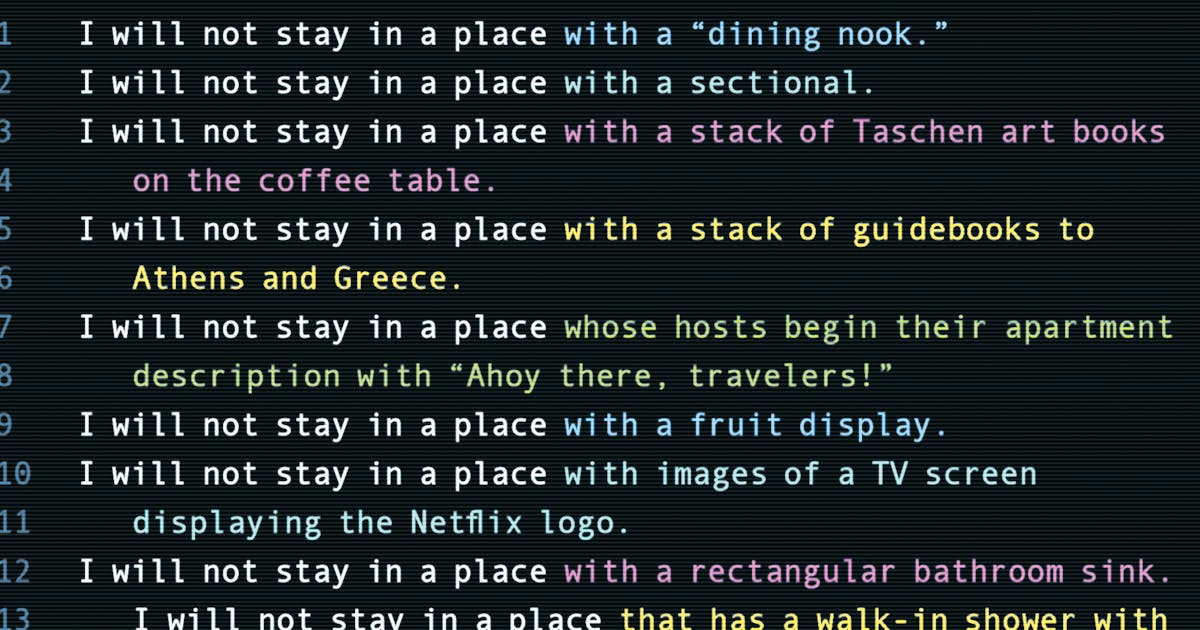

It is the age of signing open letters, then issuing apologies for signing them a few days later; of fretting about the effect of AI on human creativity, then boring anyone who will listen with “hilarious” responses generated from ChatGPT prompts; of whining about binge TV, then blasting through a whole season of The White Lotus in one night; of quitting Twitter with a melodramatic flourish, then slithering back a few months later to promote a new job or book or cause or spouse; of decrying IP’s corrosion of cinema while maintaining that Rogue One was “probably the best Star Wars film ever”; of ironizing about the pretentiousness of café culture while obsessing over the barista’s imperfect manipulation of the steam wand; of ritual complaints about the commodification of everything that reach their natural conclusion in the purchase of a new Eames chair for the living room. Contradictions abound; those of us who consume and participate in culture today—with our wallets, our words, our eyeballs, and our sneers—are all, at some level, hypocrites, complicit in the fortification of our own aesthetic prison.

Grousing about the state of culture in this poutily attentive mode has become something of a specialty in recent years for the nation’s critics. The professional critic takes the signature posture of the age—that curious mixture of derision and addiction, indifference and engagement, nausea and engorgement before the buffet of contemporary culture—and turns it into a career. “The present state of culture feels directionless,” wrote The New York Times’s critic at large Jason Farago in a recent piece. “When I was younger, I looked at cultural works as if they were posts on a timeline, moving forward from Manet year by year. Now I find myself adrift in an eddy of cultural signs, where everything just floats, and I can only tell time on my phone.” Stagnation is said to have spread to every corner of culture: music, film, literature, even clothing. New York magazine fashion critic Cathy Horyn recently wrote of a “sharp slowdown in both risk and innovators” throughout the world of haute couture: “All this accounts for a feeling of sameness, that things are stuck in place.”

Farago’s Times colleague, columnist Ross Douthat, has gone even further, publishing an entire book on the subject of cultural sclerosis. “From the academic heights to popular bestsellers, from Christian theology to secular fashion, from political theory to pop music, a range of cultural forms and intellectual pursuits have been stuck for decades in a pattern of recurrence,” he writes in The Decadent Society. From the streaky heights of media tenure, the culture has been assessed and found wanting.

Cast your eyes across this burgeoning literature of cultural stagnation—now so voluminous it counts as an authentic subgenre in its own right—and you won’t find much acknowledgment of the critic’s role in all this. Is the critic’s job simply to diagnose and decry, or to point toward a more invigorating alternative? Stagnation criticism has become every bit as repetitive—in its themes and obliviousness—as the very culture it’s critiquing, reproducing some version of the same complaint from piece to piece and book to book: that today’s movies, songs, haircuts, fonts, tables, and chairs are somehow a disappointment, that everyone now is living in some jumped-up version of an aesthetic 1993 or 1983 or 1973 or 1963, only with more trips to Portugal thrown in, a bunch of unbundled streaming subscriptions to maintain, and the need to develop an opinion on Harry Styles for some reason. We are stuck, progress has stopped, culture is bad, and it’s someone else’s fault. But whose?

Read the rest