Escaping the Cocooned Mind

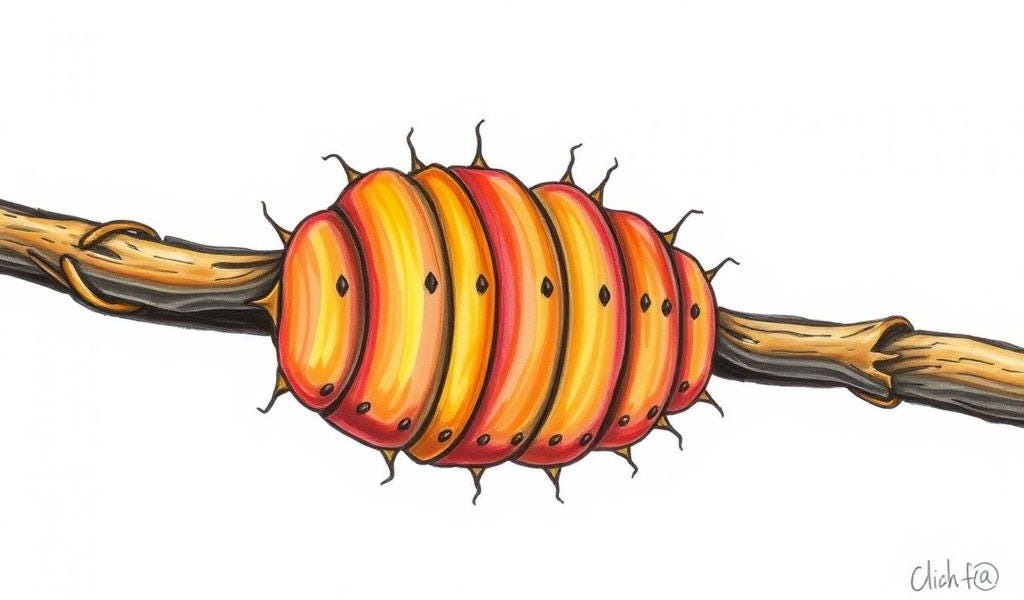

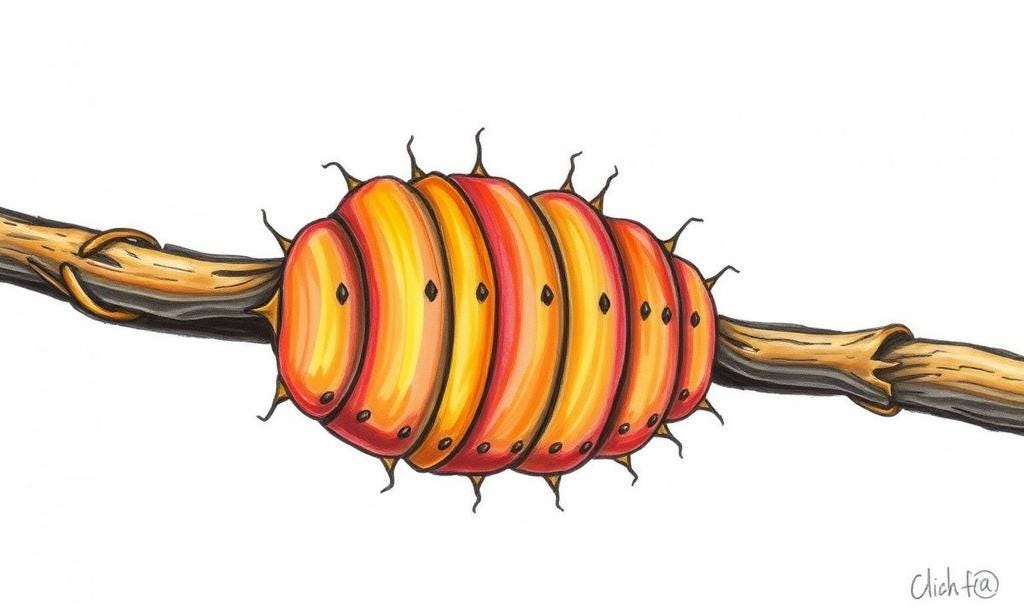

We’re all wrapped up in rationalist cocoons, spun not by our own hands but by the sticky threads of a world gone mad with reason.

Our spit’s in the walls, sure, but we didn’t design the daggone things. We were born into them, raised in them, schooled in their claustrophobic embrace until we forgot what fresh air smells like.

These cocoons feel like home but they’re prisons. They frame every thought and buffer every intuition until we can’t see the bars for the silk . . . and we come to mistake the silk for reality.

That’s why you can’t understand your own cocoon any more than a hammer can take a swing at itself. It’s the frame that holds your whole worldview together, and it’s as invisible to you as the air you breathe. To break free, you’d need something outside the cocoon: a different hammer, a sharper blade, something that ain’t already tangled in the same old threads.

Where to start? Maybe with a hard look at the left half of your brain. It loves these cocoons. When we’re in our cocoons, everything is easy: everything is safe.

Of course, everything is also false, but that doesn’t matter to the left hemisphere. The cocoon makes everyday life more certain and efficient, less stressful, at least on the surface.

From Whence All This Silk?

Psychologist Dan McAdams has provided a pretty decent description of how these cocoons develop in three stages.

First, you’ve got your dispositional frame. These are the quirks and leanings you’re born with, etched in the womb, then hammered into place by adults who see you as a tiny conservative or a pint-sized liberal before you can even tie your shoes.

Second come the characteristic adaptations, the ways you bend and twist as you stumble through childhood into the so-called real world.

Finally, there’s the life narrative: the stories we tell ourselves to get through life with a semblance of sanity (Joan Didion: “We tell ourselves stories in order to live”). These stories aren’t true, mind you, but that’s alright. They’re not entirely false either. They’re merely, in the words of Jonathan Haidt “simplified and selective reconstructions of the past” tied to some dream of the future.

They are, in other words, shortcuts: abstractions cooked up by the left hemisphere to keep us from tripping over our feet.

These stories, these narratives, are nifty tools. Even necessary. Without them, we get nothing done, falling prey to that venom known as “paralysis by analysis.”

But they’re also crutches, and just as a crutch is highly useful, if you don’t cast it aside and walk on your own, you’ll eventually develop a permanent limp: a worldview that never blossoms beyond high school or even 8th grade (I’ve met these beasts).

(Yet Another) Shot at Descartes

Ever since Descartes sauntered onto the scene, we’ve been taught to trust these rationalist crutches and shortcuts and to treat them like sacred blueprints instead of the rickety scaffolding they are. “I think, therefore I am” was Descartes’ starting point but it leads (quite quickly, btw) to an obvious and troubling ending point: “I think, there I’m right.”

If everything true comes from our brain, then everything it cranks out—including those abstract narratives full of half-truths—is dogmatically reliable.

Fixing It

So what’s the fix?

First, ditch the trust in your brain: stop worshiping at the altar of your own reasoning.

Lean on authority. I’m not talking about some guru you cherry-pick to flatter your biases, but the deep, gnarled roots of tradition and historical norms, of the sort Russell Kirk wrote about (“the permanent things”).

Drink a dose of humility by reflecting on how many times your cocoon has proven wrong. My cocoon, for instance, presents a fouled-up set of facts three times every day before breakfast. Recognize it and stare down that rationalist smugness.

Maybe try crowbarring your rationality with a few good books. There are tons out there. My all-time favorite: E.F. Schumacher’s A Guide for the Perplexed. A trendy pick that I’m enjoying: Rod Dreher’s Living in Wonder.1

Drop some acid or take mushrooms or dive into the occult. Okay, I’m kidding. Those things are obviously dark and deadly, but their popularity at least shows people are intuitively realizing they need to punch holes in these cocoons.

The bottom line is, it’s not about ramming through life like a Godzilla of rationality, stomping on everything that doesn’t fit your cocoon’s tidy little grid. It’s about stepping back, breathing deep, and admitting you might not have all the answers.

Because, brother, you don’t.

Footnote:

1 If you want something shorter (though both of those books are short), check out my feature essay: “Breaking Through to the Other Side.”

Link to Substack Platform: