Bend It Like Orwell

Essay Rules from the Master

You want to be a great essayist?

Then study the greats.

Especially Orwell.

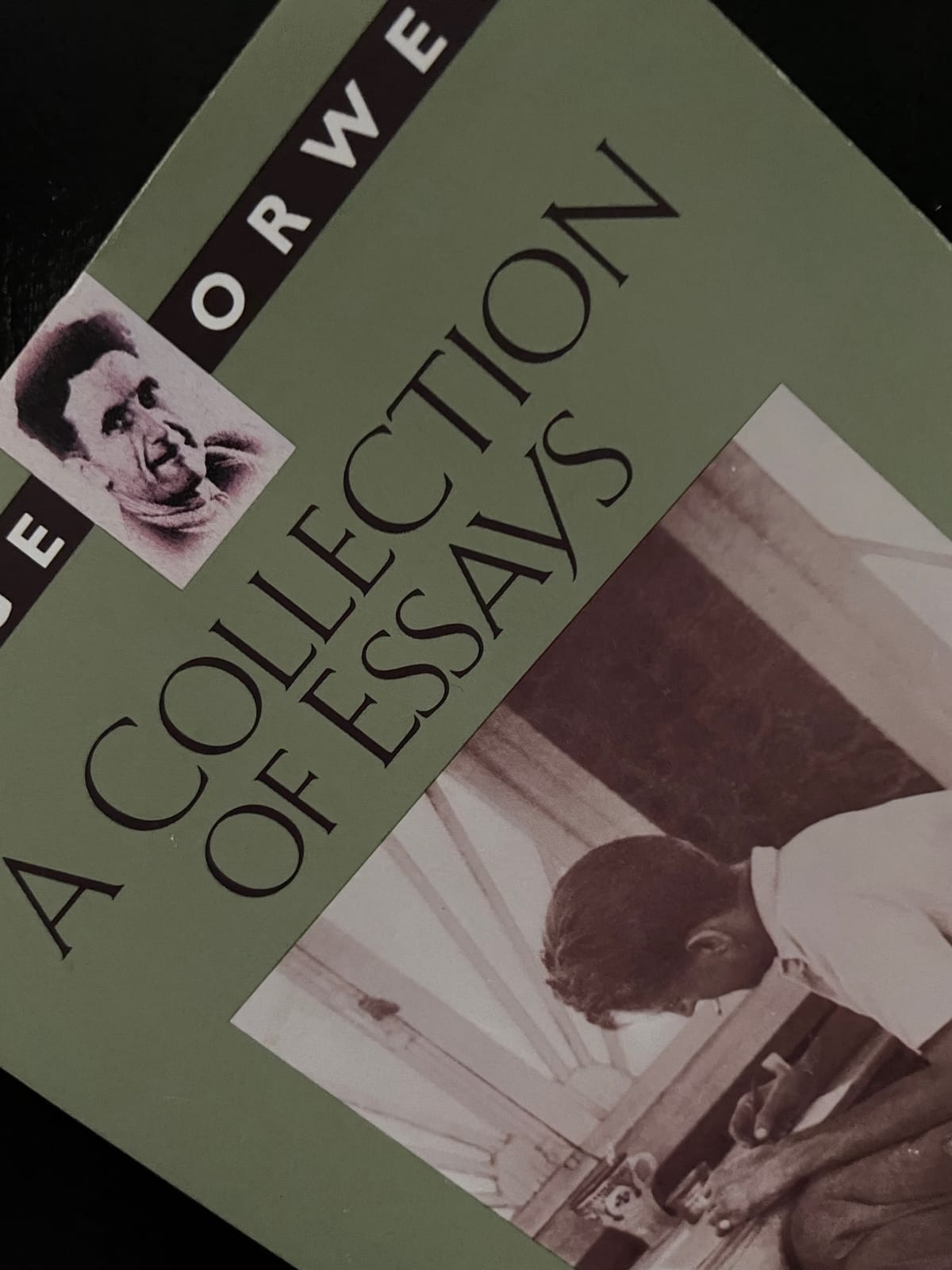

Before he wrote 1984 or Animal Farm, he was an essayist. When Irving Howe set out to write essays, he studied Orwell. Orwell was the master. He demonstrated how it’s possible to be unobtrusively interesting line after line.

Which is the First Orwell Lesson:

Be interesting.

Flannery O’Connor taught that every word in a short story should have meaning. I’d submit the same applies to essays. Every line should move the reader along an interesting continuum.

Without ostentation.

The reader, Orwell taught, shouldn’t appreciate the prose. It should be like a clear window.

You need a great lede to get the reader to look through the window in the first place.

At this, Orwell was king:

“Saints should always be judged guilty until they are proved innocent.”

“Dickens is one of those writers who are well worth stealing.”

“Autobiography is only to be trusted when it reveals something disgraceful.”

Once the reader is looking through the window, don’t smudge it with bad style.

It’s impossible to list all of Orwell’s style points, but two seem especially notable.

For the love of Eric Blair, don’t use nominalizations.

Do not murder a verb or adjective by turning it into a noun. You are in not in need of a pencil. You need a pencil. You do not have an expectation of a raise. You expect a raise.

Even the most sophomoric stylists immediately recognize a nominalization as a sign of stylistic stupor. Orwell condemns nominalization in one of the greatest essays about style ever written: Politics and the English Language, where he also spends a lot of effort to explain why writers must . . .

Avoid dying metaphors.

What’s a dying metaphor?

It’s tricky. There are, says Orwell, three classes of metaphors: The creative (one that the writer coins), the old that have become part of the English language, and the dying. The first is admirable, the sign of a poet; the second is acceptable; the third marks a lazy stylist.

They’re hard to recognize and they constantly change. A dying metaphor might morph into an old (and, therefore, usable) one. I think the best way to identify them in your writing is to read a batch of them, so here are ten samples (many of which are taken from Robert Harwell Fiske’s highly recommended The Dimwit’s Dictionary, which is a great leisurely read; merely browsing it will intuitively make you a better writer).

Good metaphors are like good jokes: they rely on making unusual connexions.

Seeing [a weak metaphor] requires no leap of imagination. A metaphor fails if it is too familiar. Its energy dissipates immediately and it dies. Iain McGilchrist, The Matter with Things, Chp. 15.

Don’t Write Like This

“It’s a jungle out there”

“behind the eight ball”

“piece of cake”

“emotional roller coaster”

“cool as a cucumber”

“hit a home run”

“pull no punches”

“quick on his feet”

“heart and soul”

“gain a foothold”

Orwell’s Six Tenets

And if you really want to bend it like Orwell, set a timer for 15 minutes, sit with your back upright, close your eyes, and meditate on these six questions that Orwell says every scrupulous writer must ask himself:

What am I trying to say?

What words will express it?

What image or idiom will make it clearer?

Is this image fresh enough to have an effect?

Could I put it more shortly?

Have I said anything that is avoidably ugly?

And Then Take It to the Next Level

I know: You don’t need to write like Orwell to make money with Internet prose. There’s a lot of stylistic trash out there that makes money. And if you spend a lot of time polishing your prose like Orwell did, you won’t crank out the volume you need to make money.

It’s a dilemma.

But isn’t life like that? You want to live beautifully, but you have to deal with that jerk at the office. You want to live for art, but you need to grub for money. You want to write poetry in timeless leisure, but you don’t even have enough time to figure out what a gerund is.

I get it. I know. We all live in this dilemma. And it sucks.

Still, we can at least recognize the dilemma: a pull of opposites, both of which merit our time and energy.

I’m afraid too many of us simply jettison one of the opposites, and it’s normally the beauty, the art, and the poetry parts.

That’s unfortunate.

It is possible to grapple with the dilemma: to live beautifully while dealing with difficulty, to write poetry when you’re not in your office cubicle, to make money while writing well.

Orwell did it.

And if we really want to bend it like Orwell, we’ll find a way to do it, too.