Dead Cars, Amish, Marx, and More

Studebaker and Other Corpses

In the wake of pending plans to discontinue Pontiac and Saturn, the Mental Floss Blog takes a look at ten discontinued models. Nice prose, nice assortment of pictures. Excerpt:

Started as the George N. Pierce Company in Buffalo, NY ”“ makers of iceboxes, birdcages, and bicycles ”“ Pierce-Arrow developed into one of the few carmakers that could actually challenge Duesenberg as American's finest automaker. Like Duesenberg, Pierce-Arrow found the market for its beautiful and frightfully expensive cars greatly diminished by the Depression. The assets of the company were sold off in 1938.

I haven't followed this idea of discontinuing models, but I think it might point to an important underlying reality: we have a better chance of preserving brands like Pontiac, if we let the Big Three file bankruptcy. Last Thanksgiving Eve, an old friend exclaimed to me, "We have to bail out the automakers. Can you imagine American roads without a Chevy? That'd be horrible."

We can debate whether it'd be horrible, but here's the thing: those brands have goodwill value. They are "intangible property" with objective value. If GM files bankruptcy, I gotta believe someone will buy the Chevrolet brand name, then put it on their cars. Granted, the car might be Toyota-made with the Chevy label slapped on, but it's still a Chevy: "Chevy" means whatever the owner of the Chevy says it means. If Toyota buys that trademark, it will then be making Chevrolets. (Of course, if the brand name isn't worth anything, it won't be bought as intangible property: nobody ran out to buy the "Edsel" name.)

But if the automakers continue to limp along, they're more likely simply to discontinue the less-profitable brands. They're less likely to sell them to a competitor, unless the exigencies of bankruptcy--including the need to present a feasible Chapter 11 reorganization plan or agreeing to sell off their assets--force them to it.

Bankruptcy isn't the end of the world, especially in the United States, which has the most debtor-friendly laws in the history of the world.

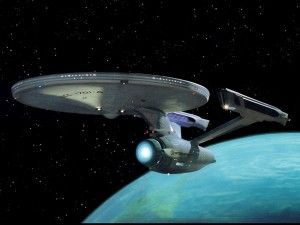

Star Trek

I saw Star Trek yesterday. Maybe it's because I was absolutely exhausted, but I didn't like it much. I'd give it a "6." I plan on going to the next one they issue, and I wasn't terribly disappointed, but they could've done a much better job. The special effects were great--so great, in fact, that you could barely tell what was going on at times. I wish Hollywood would get this through its head: special effects should illuminate, not obscure.

I wish they'd also get it through its head that a coherent plot should take priority over special effects, and I wish they'd get rid of the mindset that every movie needs a sex scene. There was a 60-second bedroom scene that served no purpose whatsoever (Captain Kirk on some green chick). Strictly gratuitous. Why?

Red Radio

When I first started following politics back in the 1980s, one of the first things I learned was, "Don't trust National Public Radio. It's hopelessly leftist." Nonetheless, I've always listened to it a fair amount. I've enjoyed many of its segments, and I think it shifted more to the center after the 1994 Republican revolution.

But it would appear NPR leftists are feeling pretty safe now, with the executive and legislative branches back on their side. I was stunned at this laudatory piece about Marx that I found last night. Excerpts:

Those of us now cracking open Marx will find he had much to say that is relevant today, at least for those looking to "recover the spirit of the revolution," not merely to "set its ghost walking again." . . .

Attempts to talk seriously about the need to democratize our economies in such radical ways were largely shunted aside by parties of all stripes for the next several decades, and we are still paying the price for marginalizing those ideas. The irrationality built into the basic logic of capitalist markets–and so deftly analyzed by Marx–is once again evident. Trying just to stay afloat, each factory and firm lays off workers and tries to pay less to those kept on. Undermining job security has the effect of undercutting demand throughout the economy. As Marx knew, microrational behavior has the worst macroeconomic outcomes. We now can see where ignoring Marx while trusting in Adam Smith's "invisible hand" gets you. . . .

If he were alive today, Marx would not look to pinpoint exactly when or how the current crisis would end. Rather, he would perhaps note that such crises are part and parcel of capitalism's continued dynamic existence. Reformist politicians who think they can do away with the inherent class inequalities and recurrent crises of capitalist society are the real romantics of our day, themselves clinging to a naive utopian vision of what the world might be. If the current crisis has demonstrated one thing, it is that Marx was the greater realist.

Do I really need to recount the dangerous ideas Marx unleashed, the terrors of Lenin and Mao, the bankruptcy of the USSR, the free market's very good record (capitalism is a bad system, but it's better than all the others)? I'm not going to wear myself out. If the world is going to hell with that much celerity (Maobama has been in power for only four months), there's nothing I can do about it. I'll take solace in my books, my two guns, a little bread, and my children. Tolstoy derided familial narcissism ("the world can go to hell, as long as everything's okay with my little Andrei"), but in this world of difficult individuals (I've experienced a rush of 'em lately) and a threatening government, a guy has to take solace where he can find it.

Amos Gettin' His

I know many Amish. I work for them, they work for me. A few I even consider friends. So this story (from my region) greatly interested me:

Suffering steep unemployment following a decades-long shift from farming to factory work, a growing number of the area's 23,000 Amish are breaking with centuries of tradition and taking government help to stay afloat, church and economic leaders say.

Bishops who once might have censured those who sought public assistance are reluctantly looking the other way.

I kind of take issue with the reference to "government help." The article is talking about unemployment benefits, not welfare and food stamps. As a person works, his employer puts money into the state unemployment fund. The contribution rate depends on an employer's experience rating: the more workers you lay off and fire, the higher your contribution rate. For new employers, the rate is around three cents for every dollar of wages.

Of all the types of public assistance, I don't hate it in practice (in theory, I detest it like I do all forms of governmental paternalism), since the benefits help a person who actually held down a job and cushions a blow when a person needs it most. Plus, the system is at least partially accountable (through the experience contribution rate calculation).