Risk Taking

Rage in the Manhattan Cage

I saw a piece from New York Magazine making cyberwaves last week, but I decided not to post about it until I had a chance to read it. I read it during my nephew's baseball game on Saturday: The Wail of the 1%.

The gist: The over-paid fund managers and related professionals are mad at their vilification in the press and at Obama's tax hikes.

“I'm not giving to charity this year!” one hedge-fund analyst shouts into the phone, when I ask about Obama's planned tax increases. “When people ask me for money, I tell them, 'If you want me to give you money, send a letter to my senator asking for my taxes to be lowered.' I feel so much less generous right now. If I have to adopt twenty poor families, I want a thank-you note and an update on their lives. At least Sally Struthers gives you an update.”

The article does a pretty good job of trying to be fair to such petulance, but it didn't really delve into the real issue: Wall Street's penchant for saying they deserve all that extra money because they're so talented and they work so hard and they do so much for America's economy in general (all true statements, to some extent), but then going to Washington, DC for help. They appealed to Washington after the great fire of 1835 gutted lower Manhattan (Andrew Jackson told them to drop dead), Wall Street and its nationwide tentacles did it in the Savings and Loan Crisis of the 1980s. It's not deregulation (always a familiar cry in the MSM) that leads to these crises and resulting bailouts. It's the bailout mentality itself. It distorts the risk-taking.

Go to a casino sometime and gamble with your money. How much you gonna put into the slot machines or on the crap table? $5? $500? $5,000? Doesn't matter: It's your money, so you're going to be somewhat careful. Now go to the casino with my promise to reimburse your losses: If you win big, you keep it all. If you lose big, I'll reimburse you. What are you going to do? Be cautious? If so, you're a fool. You should shoot for the moon.

And that's what happens in the financial world. The New York article quotes Professor Mitchell Moss saying, “You basically had a casino culture operating in the financial-services industry.” Professor Moss is only half right: You had a casino culture with a distorted risk of loss operating in the financial-services industry."

There's a mindset on Wall Street that they can be aggressive and take big risks. If things go well, they earn an obnoxious amount of money (as they did from 1990 to 2008). If things go to hell in a handbasket, they can appeal to Washington for help. Allan Meltzer recently commented that he doesn't think this is an explicit part of Wall Street's decision-making, but he says it's a shadowy part of the mental landscape, a comfortable old chair sitting in the Wall Street family room that no one really thinks of using, but is still there if the rest of the furniture is suddenly whisked away. The mentality is kind of captured in this passage from the article:

Part of the problem, the Goldman vet explains, is that there's a vast divide between where the public is and where the bankers are. The public registers how fundamentally the system has changed; the bankers are far from getting to that point. “When I talked to my friends in November and December at firms like Goldman, they would tell me, 'If the government doesn't bail us out, we're going down.' They really thought they were going to zero, and without exception, they all forget that now,” he says. “They forget that their company's stock was going to zero. It's a state of delusion; they don't remember those days. The flip side of that is, every guy except the Goldman guy remembers that Goldman was bailed out.”

When things are good, the financial sector flies recklessly forward, reaping the benefits. When things go bad, it's quickly looking to Washington.

The result is a huge distortion in risk-taking. Eventually, one of the risks goes horribly awry. Then the result is a bailout, then a cry for more regulation (which we're seeing). And I sympathize: If the federal government pays for it, it gets to regulate and control it. That's why I get to tell my kids what to do: I'm responsible for them, I have to pay for their screw-ups.

But that's not the correct answer. Regulation suffocates and stifles. The answer is to tell the financial world: "No more. If you screw up again, you can wear a barrel around your shoulders and beg for money. You can do what you want, but there sure won't be another bailout."

It's easier said than done, of course, but we need to. And we need to do it now. Unfortunately, that's not the type of change the current administration believes in.

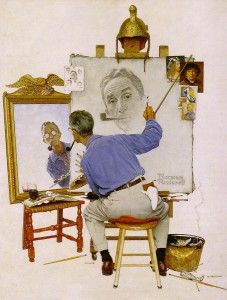

Autobiographical Corner

We split the family this weekend: Marie took the two young girls to Detroit for a baby shower, I stayed here with the other five. It worked out fairly well, but she took the sports car (the minivan) and left me with the Amish hauler (12-person Ford Econoline van, named after the tendency of people in these parts to use such vehicles to transport the Amish for a fee).

I had to cart kids to soccer, baseball, a sweet 16 birthday party 12 miles outside of town, Dollar Tree to buy birthday presents for their brother, and confirmation class . . in the clumsy Amish hauler. I dislike driving that vehicle, but I am encouraged that I found the weekend rather easy. Five years ago, I would've been overwhelmed by the non-stop kid events, but this weekend, I handled them all and even found an extra hour to attend my nephew's varsity baseball game.

Part of the "ease" comes from my resignation to a simple life, devoid of serious literary or scholarly endeavor. After twenty years of gulping at such troughs, trying to squirrel away whatever time I could and growing frantic when all time was zapped from me, I'm now just happy to get 30 minutes on a Saturday afternoon with a serious book and 45 minutes on Sunday, interspersed with whatever reading time comes my way during the rest of the week. I don't feel any dumber, which may, of course, be a sign that I'm getting a great deal dumber . . . but at least my heart doesn't feel like it's ready to explode throughout the week as yet-another kid or family obligation knocks on my door.

Best Passage from Weekend Reading

"W. H. Auden, who referred to himself as a New Yorker and never an American, would not leave his apartment on St. Mark's Place without carrying a five-dollar bill, lest a mugger, angry at finding him without money, beat him up all the worse." Joseph Epstein, The Middle of My Tether: Familiar Essays (Norton, 1987), p. 66.

(I'll be featuring more Epstein later this week.)

Heed Auden's Advice Here

America's Most Dangerous Cities, according to Forbes.

10. Baltimore

9. Nashville

8. Charleston

7. Little Rock

6. Orlando

5. Stockton (CA)

4. Las Vegas

3. Miami

2. Memphis

1. Detroit

Six are in the old Confederacy, which also owns four of the cities from 11-15 on the list--or 2/3rds of the Top 15.

I'd never even heard of Stockton, until we drove by exits for it on our way to Fresno. I'm glad we didn't stop.

Looking for a Catholic speaker? Check out CMG Booking.

10 Divorce Stories Too Strange to Make Up

Best foreign website I've ran across in quite awhile: Russia Today. It's one of those websites that makes you wish you had oceans of free time, so you could surf for hours.