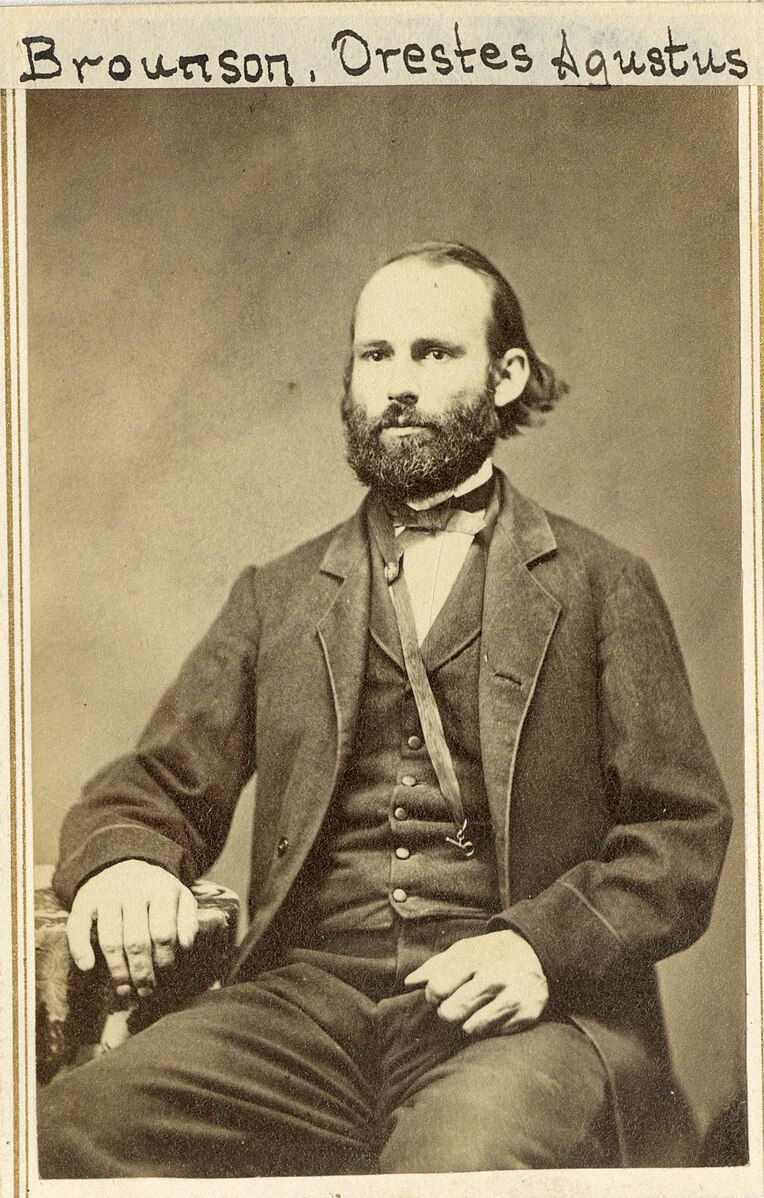

Orestes Brownson: The Forgotten Transcendentalist

Part I of a Five-Part Series

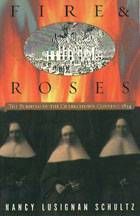

America was not a pretty place to be a Papist in the second quarter of the nineteenth century. Things had previously been fairly peaceful for the Catholics, but in the 1820s Catholic immigrants started to swarm into the States. Irish Catholics swamped the East Coast; German Catholics settled the Mississippi Valley; and Catholicism became known as the religion of lower class people who talk, look, and smell odd. Anti-Catholic bias rose sharply, as did incidents of attacks on Catholics.

In 1834, Samuel F.B. Morse, of Morse Code fame, published his Catholic-bashing Foreign Conspiracy against the Liberties of the United States. Also in 1834, a New England mob attacked a Catholic orphanage in Charlestown, expelling the nuns and girls, then ransacking, robbing, and torching it with impunity. In 1836, Maria Monk's Awful Disclosures of the Hotel Dieu Nunnery in Montreal purported to reveal the pornographic conduct and child-killing ways of nuns in Montreal; the book sold briskly and Maria Monk became a lecture circuit feature (the book was wholly fraudulent; a project hatched by Protestant ministers to discredit the Catholic Church). In 1843, the organization that would eventually become the American Party (a/k/a Know Nothing Party) took shape with the aim of excluding Catholics from public life. In 1844, a three-day anti-Catholic riot took place in Philadelphia, destroying several churches and injuring or killing sixty-three people.

Also in 1844, Orestes Brownson converted to Catholicism.

It was an odd jump, both for the times and a man of his public stature.

Born on September 16, 1803, the last of five children, in Stockbridge, Vermont and a New England heavily-influenced by Puritanism and Congregationalism, Brownson didn't even see a Catholic Church until his early twenties when he moved to Michigan for a short spell in 1824. His exposure to Catholicism was similar to rural youngsters today who don't see a mosque or temple for the first time until they leave their home town; for such youngsters, Islam and Judaism tend to be stamped as wholly exotic and beyond the pale of serious religion, much less a potential home of one's religious pilgrimage.

Born of Presbyterian parents, his father died when he was young, probably at age six. His poverty-bitten mother sent him to nearby Royalton, Vermont to be raised by an elderly farm couple. He stayed there for about eight years, until 1817 when his mother re-united the family and moved them to Ballston Spa, New York.

He formally joined the Presbyterian Church while living in Ballston Spa, in 1822, at age 19. But he did not remain a Presbyterian for long. The need to give fair play to both faith and reason seems to have pressed on Brownson from his earliest adult years, and he soon found the Calvinist-based Presbyterianism of his parents repugnant to reason. He also disliked the Presbyterian Church's ambivalence toward its authority: on the one hand, it said each person must read the Bible and determine for himself what doctrines to believe; on the other, it asserted the right to condemn and brand a person a heretic if he deviated from accepted doctrines. Brownson said he could accept authority or no-authority, but the church he joined had to be consistent.

For the time being, he opted for no-authority, except the reasoning of his own mind. To develop his new-found authority, he plunged himself into a demanding intellectual life and started to study the great writers of western civilization.

He also schooled himself in the thoroughly-rationalist religion of Universalism and asked the Universalist General Congregation for a letter of fellowship (a license to preach), which he obtained in late 1825, and was later ordained a full Universalist minister in mid-1826. For the next three years, he moved constantly, practicing his ministry in different New England towns, pausing to marry Sally Healy in 1827, publishing his first articles, and assuming his first editorship position (of The Gospel Advocate, an influential Universalist publication).

This constant “on-the-move” disposition was a part of Brownson's life, especially during his first forty years. An example of his whirl of activity can be sensed by a cataloguing of his activities during the eighteen months from late 1829 to early 1831: collaborated with free-love and women's right pioneer, Fanny Wright, and became an editor of her radical, atheistic journal, the Free Enquirer; became involved in the labor movement and attempted to establish a labor journal in western New York; severed ties with the Free Enquirer; severed ties with the Universalists and became an independent preacher; became editor and publisher of The Philanthropist; became a father for the second time (first son, Orestes Jr., was born in 1828; second son, John, in 1829).

After this span, he spent months as an itinerant preacher, then settled as a Unitarian pastor in Walpole, New Hampshire. While in Walpole, he published widely, lectured at distinguished venues in New England, and became acquainted with William Ellery Channing, George Ripley and other persons who would become the vanguard of the Transcendentalist Club in Boston. He was attracted to their ideas and their personalities (later even naming one of his sons after Channing). In 1834, after two years in Walpole and eager to get closer to the stronghold of Unitarianism and the Transcendentalists in Boston, he accepted a call to become pastor of a Unitarian congregation in Canton, Massachusetts where he became friends with Henry David Thoreau.

Two years later he left the clergy altogether and moved to Chelsea, Massachusetts where he started the Society for Christian Unity and Social Progress, an effort to unify all Protestant sects under one banner in order to further the cause of progress. The heady enterprise lasted three years. During this time, he became editor of The Boston Reformer and established his name as a top literary figure in New England. Two years later, in 1838, he launched the Boston Quarterly Review, which would later be re-named Brownson's Quarterly Review and be his primary occupation for most of his life.

This willingness to move physically paralleled his tendency to keep his mind moving. During these years he continued the intense studies he began at age twenty. A partial list of the writers he studied in his late twenties/early thirties shows that Brownson was willing to grapple and tackle any philosopher or theologian in his quest to grasp ultimate truths: Locke, Kant, Hume, Saint-Simon, Fourier, Cousin, Constant, Leroux, Gioberti, Liebniz, Channing, Paley. In addition to these authors, he studied languages: Latin, French, German, Spanish, Italian, classical Greek (mastering Greek and Latin well enough to read the church fathers in their original languages).

In 1836, he became a founding member of the Transcendentalist Club, a loosely-organized group of highly-educated men and women with eclectic tastes. Although it is hard to categorize the members, the group was mainly composed of Unitarians with a tilt toward subjectivism, intuition, optimism, utopianism, and social reform. In the religious sphere, they reduced belief in God to a process of self-deification, where God was found to be each man's soul and each person deemed entirely–religiously and otherwise–self-sufficient. The Transcendentalists, unsurprisingly, dismissed Catholicism as the lowest form of ceremonial superstition. Although Brownson had an important voice in the Club, he disliked its emphasis on self-deification and the members' preference for abstract theories and disdain for practical matters, and soon found himself deviating from it.

As editor of the Boston Quarterly Review, Brownson staked a place for himself as an advocate of truth in the highest things: religion, philosophy, literature. He wrote the bulk of each Review himself, a mammoth task since each issue consisted of six essays and approximately one hundred pages. The Review quickly gained a respectable number of subscribers, and was widely read among America's influential classes.

In 1840, he used the Review to publish his essay, “On the Laboring Classes.” It was a thundering polemic against wage slavery, the churches that helped bring it about, and the rich industrialists who bribe politicians to keep it going. It contained highly-radical assertions, and the popular press raised a storm of protest against its socialist ideas. 1840 was also the year of a hot presidential race between Democratic incumbent Martin Van Buren and Whig candidate William Harrison. Brownson sided with the Democrats, and the Whig Party reprinted his essay in the tens of thousands and distributed it as proof that the Democratic Party favored socialism. Van Buren lost the election, and supposedly largely attributed his defeat to Brownson's essay.

It was out of the radical politics that reached its zenith in that essay, and the religious liberalism of Unitarianism and Transcendentalism, that Brownson would leap into the Catholic circle. After twenty years in the lands of leftist Christianity–Universalism, Unitarianism, Christian Socialism, Transcendentalism–he turned to the right . . . and into the arms of the Catholic Church. No middle ground, like Episcopalianism. His was a straight jump over the Tiber, more eager than his jump over the River Charles to Unitarianism and Transcendentalism years earlier.

__________________________

An edited version of this article appeared in Logos: A Journal of Catholic Thought and Culture. I'm pretty sure I kept the copyright.