What de Lubac Would Think About the Synod on Synodality

Robert Imbelli at First Things

Henri de Lubac, S.J., one of the twentieth century’s greatest Catholic theologians, was among the prominent figures in the ressourcement movement that prepared the way for Vatican II. Indeed, many of his writings influenced the very terms employed by the Council, especially in the constitutions on the Church (Lumen Gentium) and on revelation (Dei Verbum). During his long theological ministry, stretching from the early 1930s to the early 1980s, not only did he insist on the intimate bond between theology and spirituality, he also witnessed to the inseparability of the dogmatic and the pastoral in his courageous opposition to Nazism and anti-Semitism. His last major theological work, completed despite declining physical force, was the almost one-thousand-page volume La posterité spirituelle de Joachim de Flore (The Spiritual Posterity of Joachim de Flore). Unfortunately, it is not yet available in English. But its reflections are most helpful today as we consider the Church's ongoing Synod on Synodality and its recently released Instrumentum Laboris (working document).

De Lubac had first treated the twelfth-century mystic at length in the third volume of his Exégèse Médiévale. He concentrated upon Joachim’s distinctive approach to Scripture, in particular his view that there would be a “third age” of the Spirit that would supersede the ages of the Father and the Son (represented by the Old and New Testaments, respectively). On de Lubac's reading, the thrust of Joachim’s prophetic vision was to call into question the saving finality of Jesus Christ. In Joachim's “third age,” the “Spirit” in effect becomes separated from Christ and fuels pseudo-mystical and utopian movements. For without the objective Christological referent and measure, appeal to the Spirit easily falls prey to subjective ideologies and fantasies.

Already here, de Lubac glimpsed the long and troublesome “afterlife” of Joachimism, including its schismatic propensities. He began to explore the variety of movements, both secular and quasi-religious, that, much like Joachim, envisioned the arc of progress bending toward a “Third Age” fulfillment, whether in Hegelian, Marxist, or Nietzschean forms. In all of these movements Jesus Christ was deemed at best a penultimate word, and the Church considered but the relic of an unenlightened age.

De Lubac took up the mammoth task of writing his book on Joachim’s posterity because he discerned that the period after the Council was marked in many circles in France and elsewhere by a recrudescence of Joachimite sensibilities and projects. These Joachim-like tendencies plot a way beyond the parochialism of the “institutional Church,” toward the celebration of a universal humanity, liberated from the constrictions of law and hierarchical order.

In his moving memoir, At the Service of the Church, de Lubac comments on the “circumstances that occasioned his writings.” He makes clear that his book on Joachim’s posterity was animated not by merely academic interests, but by his sense of a present danger: the danger of betraying the Gospel by transforming the search for the kingdom of God into a search for secular social utopias.

TDE Notes

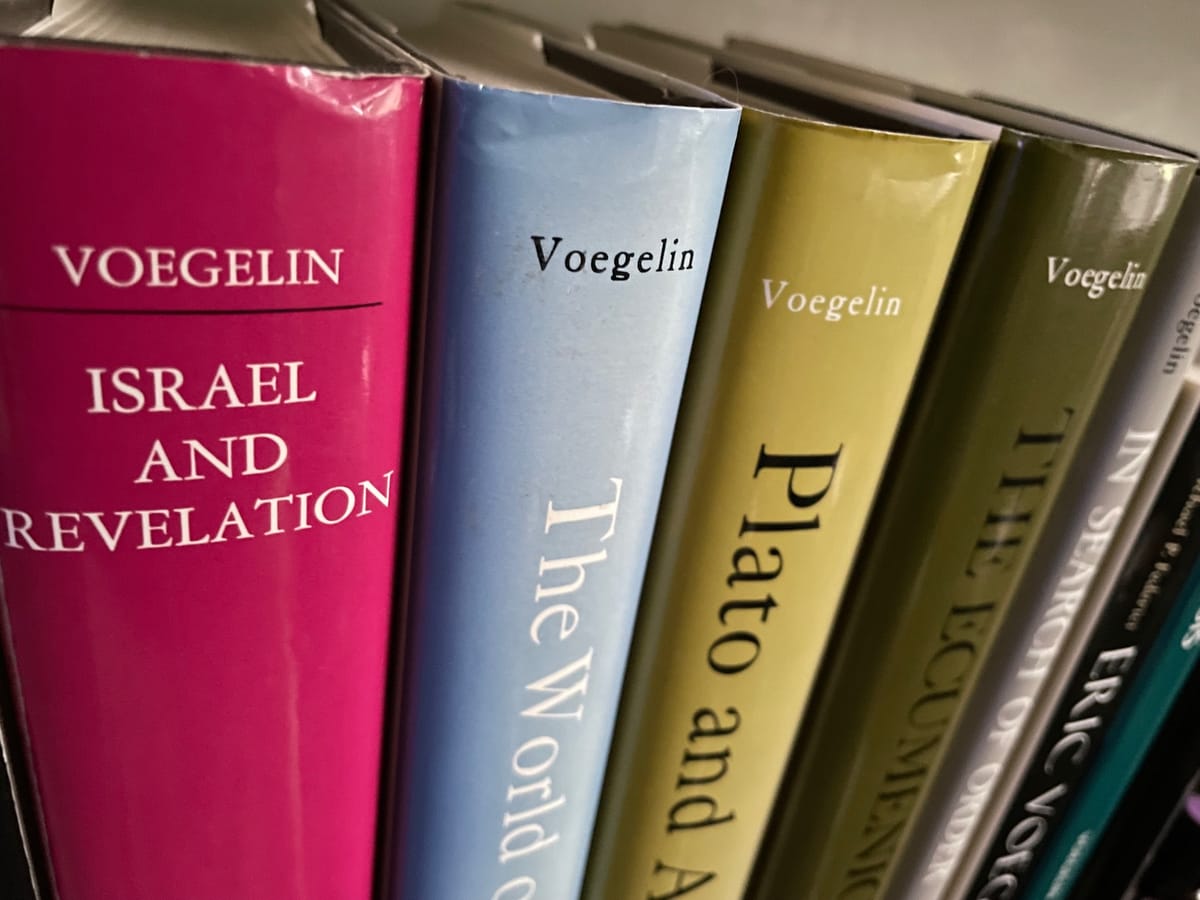

Voegelin's The New Science of Politics spent much time on the thought of Joachim de Flore. I just don't know if Voegelin informed de Lubac or de Lubac informed Voegelin . . . or it was thoroughly symbiotic. They were exact contemporaries (coming into and leaving the earth within five years of one another), so there are no clues there. De Lubac's Drama, which influenced Voegelin, came out in 1944, for what it's worth.