These Six Traits Make a Person a Gnostic

A Diagnostic of the Gnostic

Eric Voegelin was to modern gnosticism what Knute Rockne was to Notre Dame football. Rockne didn’t start the ND football program and Voegelin didn’t discover modern gnosticism, but they took their subjects to much higher levels.

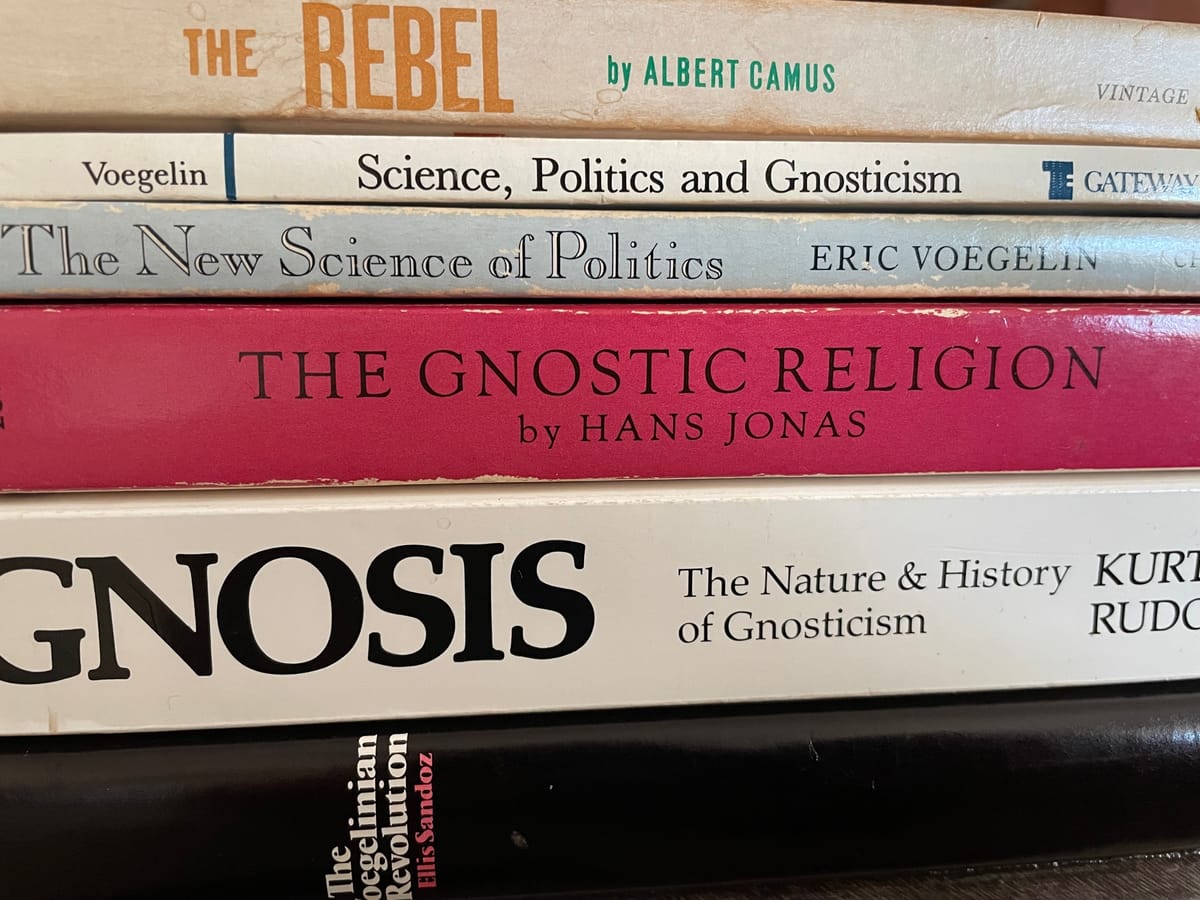

The Swiss theologian, Hans urs Von Balthasar was supposedly the first person to draw parallels between the ancient gnostic heresy and modern theories in Prometheus (1937), which examined modern German thought. Albert Camus did a similar thing with modern French thought in The Rebel (1951).[1]

But Voegelin took the strain of thought much further in The New Science of Politics (1952). The book became a Time cover story and, voila, gnosticism was in the limelight, a least among nerds.

Granted, later in life, Voegelin said he wasn’t sure “gnosticism” was the best term to use and thought perhaps it received too much attention, but he didn’t remotely conclude that the term didn’t work. Far from it. Later in life, at age 67, he published his most popular work, Science, Politics and Gnosticism in English (1968) (He had earlier published it in German (Wissenchaft, Politik, und Gnosis) in 1959.)

We Need to be Careful When Tossing around that Term

Gnosticism is both precise and vague. It’s vague, in the sense that it touches on the Tao (the unnamable) and transcendence. It’s precise, in the sense that specific characteristics need to come together in order to keyhole someone as a gnostic.

We tend to label opponents. We all know the phenomenon: if we can label a person, we can dismiss a person. It’s practically a trope that doesn’t even need to be mentioned, but most of us tend to do it anyway.

“Ah, he’s just a gnostic. F’ ‘im.”

Voegelin himself expressed concern that we would over-use the gnostic label to characterize anyone we disagree with in politics, thereby watering it down to the point that it’s no longer useful for analyzing the modern political world.

He didn’t need to be concerned. We already had a term for that: “Fascist.”

Still, people have used gnosticism in the same way. A little while ago, I read a moron who claimed that Trump is a gnostic. Such a thing is absurd. Trump might be wrong. He might be a demagogue. He might be a lot of unfortunate things. But a gnostic? Not even close. He’s not even on the gnostic spectrum (more on that later).

The Gnostic Attitude

In Science, Politics and Gnosticism, Voegelin set forth the six traits that, together, “reveal the gnostic attitude.” You can read Voegelin’s exact words in the footnotes.[2]

I want to apologize: It’s dry stuff, but it’s not my fault. It’s not even Voegelin’s fault. We’re dealing with a difficult subject and he was breaking a lot of new ground. He probably didn’t have the time (nor inclination, based on his biographical details) to water it down for popular consumption.

That’s why I’m trying to do it in this series of essays. I want to be the Voegelin vulgarizer.

And I’m starting by trying to recast the six gnostic traits in the framework of the Existence Strikes Back project.

I want to be honest: This has been hard. Very hard. I’ve rewritten the six traits five times in the past week and, prior to that, I’d done it about ten times.

But I think I have it close enough for now. I might tweak it as the ESB project unfolds, but Voegelin continually tweaked his analysis as the years went on, so maybe I’m in good company.

Anyway, here are the six characteristics that, in Voegelin’s words, “taken together, reveal the nature of the gnostic attitude,” but recast in the “Existence Strikes Back” framework:

1. Existential dissatisfaction/anxiety/unhappiness.

2. Belief that the dissatisfaction is because the world is poorly organized.

3. Belief that (2) can be remedied, which will result in (1) being alleviated.

4. A rejection of the Reality Spectrum, in the sense that, by rejecting a part of the Reality Spectrum, the gnostic hopes to effect his or her own salvation through historical processes.

5. Belief that he or she, or the movement or cause, can effect (3).

6. Belief that special knowledge gives the ability to effect (3) by implementing the flawed understanding of reality.

Prometheus was the Arch-Gnostic

I plan on dedicating an essay to each of the six characteristics, but for now, I want to illustrate the gnostic mindset through the lens of Aeschylus’ Prometheus Bound (discussed here).

I think it’s a great starting point to vulgarize Voegelin. It’s a well-known work, English translations are available in the public domain for anyone who wants to read it for himself, and it’s short (you can read it in about an hour).

I think Voegelin would approve of my approach. He focused on Prometheus Bound twice, first in The World of the Polis (1957) and again in Science, Politics and Gnosticism (1968).

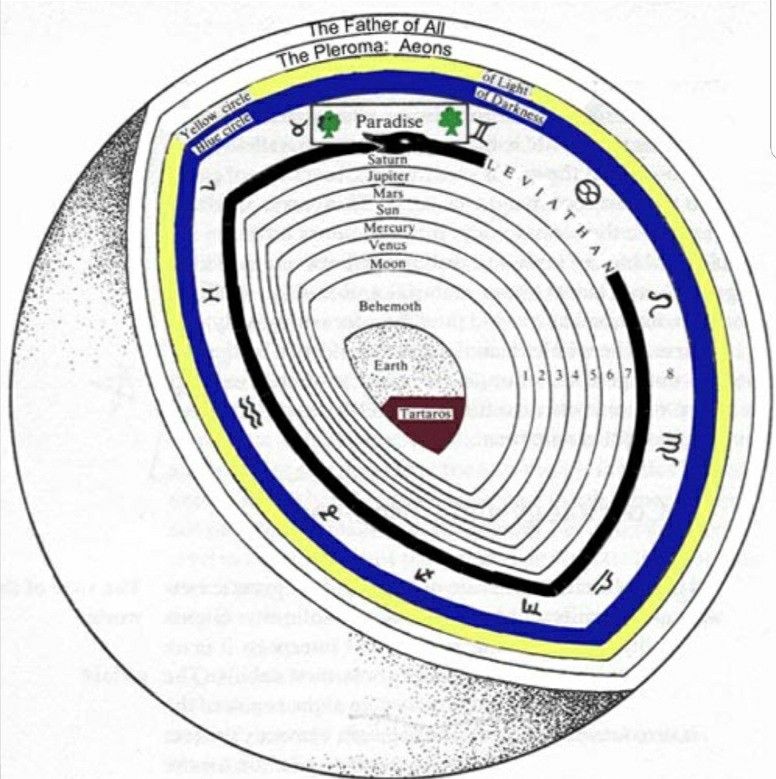

A quick note: When thinking about Prometheus Bound, it’s crucial to remember that “Zeus” = The Reality Spectrum and “Prometheus” = any person who rejects it in preference for his own reality (the gnostic).

Here’s a summary of the play, with each of the six gnostic traits referenced in the parentheses:

Prometheus was the unhappy/restless man (1) who believed his unhappiness resulted from a world poorly organized by Zeus (2), and that he would be content if the world were properly organized (3). He carried out his plans without regard to Zeus (4) and insisted that his plans would bring about a proper world (5) because he possessed ancient and immense intelligence (he was older than Zeus and probably smarter than Zeus) (6).

Rephrased:

The gnostic is the unhappy/restless man (1) who believes his unhappiness results from a world poorly organized (2), and that he could be happy if only the world were properly organized (3). He carries out his plans without regard to the Reality Spectrum (4) and insists that his plans will bring about a proper organization of reality (5) because he possesses the tools (intelligence, know-how, method, etc.) to do it (6).

Rephrased even further:

The gnostic is a malcontent who thinks his discontent comes from outside himself (reality) and that he would be happy if reality were organized in the gnostic’s preferred manner. The gnostic believes reality can be changed and that he or a leader or a movement has the tools to do it.

Bear with me as we go through gnosticism in the coming months.

And trust me: it’s riveting stuff. I will make it exciting . . . or at least not boring. I might even be able to incorporate a few sexual references (gnostics have often been perverts) to make it fully accessible to the modern mind.

[1] https://voegelinview.com/gnosticisma-brief-introduction-pt-1/

[2](1) It must first be pointed out that the gnostic is dissatisfied with his situation. This, in itself, is not especially surprising. We all have cause to be not completely satisfied with one aspect or another of the situation in which we find ourselves.

(2) Not quite so understandable is the second aspect of the gnostic attitude: the belief that the drawbacks of the situation can be attributed to the fact that the world is intrinsically poorly organized. For it is likewise possible to assume that the order of being as it is given to us men (wherever its origin is to be sought) is good and that it is we human beings who are inadequate. But gnostics are not inclined to discover that human beings in general and they themselves in particular are inadequate. If in a given situation something is not as it should be, then the fault is to be found in the wickedness of the world.

(3) The third characteristic is the belief that salvation from the evil of the world is possible.

(4) From this follows the belief that the order of being will have to be changed in an historical process. From a wretched world a good one must evolve historically. This assumption is not altogether self-evident, because the Christian solution might also be considered – namely, that the world throughout history will remain as it is and that man’s salvational fulfillment is brought about through grace in death.

(5) With this fifth point we come to the gnostic trait in the narrower sense – the belief that a change in the order of being lies in the realm of human action, that this salvational act is possible through man’s own action.

(6) If it is possible, however, so to work a structural change in the given order of being that we can be satisfied with it as a perfect one, then it becomes the task of the gnostic to seek out the prescription for such a change. Knowledge – gnosis – of the method of altering being is the central concern of the gnostic. As the sixth feature of the gnostic attitude, therefore, we recognize the construction of a formula for self and world salvation, as well as the gnostic’s readiness to come forward as a prophet who will proclaim his knowledge about the salvation of mankind.

Eric Voegelin, Science, Politics and Gnosticism (Regnery Gateway, 1968), p. 86.

Further reading

https://www.catholicworldreport.com/2021/01/31/the-gnostic-heresys-political-successors/