The Original Deep States

Wilfred McClay at the Claremont Review of Books

The French have a term for the vast interior of the North American continent lying between the Alleghenies and the Sierras: l’Amérique profonde. Its meaning is variable, although tending toward a casual Gallic dismissiveness that seems to be obligatory. In other words, the modifier profonde, deep, is usually meant ironically. But it also conveys the sense that there is a real America beyond the coastal encampments, something not merely provincial but dark, shapeless, vast, and unknown. Perhaps even “deep,” in some primitive way. Although still probably not worth knowing any better than that—not really.

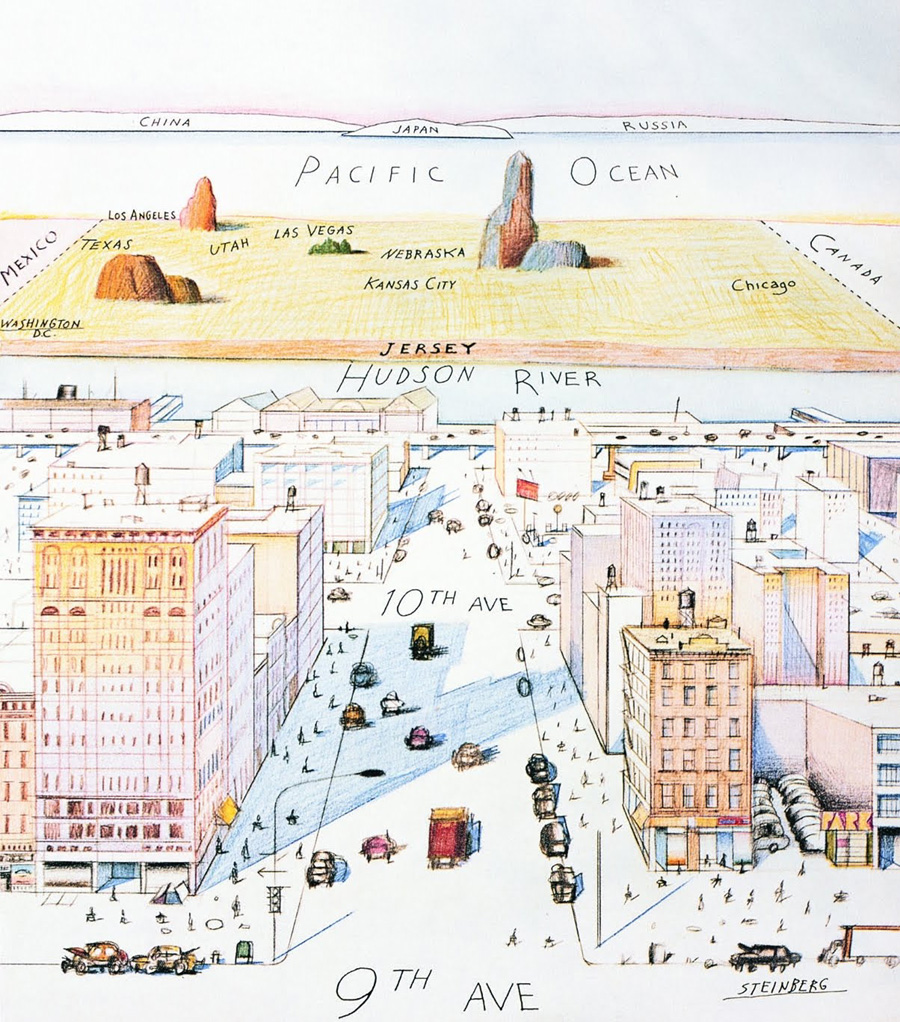

The sense being described here is akin to that of Saul Steinberg’s depiction of America west of the Hudson in a classic cover for The New Yorker (March 1976) called “View of the World from Ninth Avenue.” You know the one I mean, in which the bottom two thirds render in great detail the humming life of the West Side of Manhattan, while the rest of America is depicted in the remaining third as a three-block-wide green rectangle, flat as a cement floor, bordered by white slivers called “Canada” and “Mexico,” with a few rock formations and a handful of city and state names thrown in to break up the monotony. Steinberg was both mocking and celebrating New Yorkers’ sophisticated provincialism, and the illustration’s immense popularity ever since bears witness to that perspective’s enduring appeal. (As the song says, it’s a hell of a town.)

Sectionalism has been one of the great themes of American history, and the interplay among America’s urban, rural, and regional cultures has long been one of the most interesting factors in our national life. But the flattening and homogenization of the country over the course of the 20th century has rendered this aspect of our national life less and less visible, and hence less vibrant. The steady decline of genuinely independent regional and local newspapers and other news outlets is but one sign of this loss. Another is the fading interest in savoring the particularities of place: history, geography, culture, food, climate, local business, anything that distinguishes one locale from another.

***

No section of the country has suffered more from this process of national homogenization and stereotyping than the Midwest, as Jon K. Lauck well knows. An adjunct professor of history and political science at the University of South Dakota, he is the founding president of the Midwestern History Association and the editor of the Middle West Review, a journal dedicated to the study of the American Midwest. In addition, he is the author of several books, including The Lost Region: Toward a Revival of Midwestern History (2013), From Warm Center to Ragged Edge: The Erosion of Midwestern Literary and Historical Regionalism, 1920–1965 (2017), and his latest, The Good Country: A History of the American Midwest, 1800–1900.

Over a century ago, well before the onset of economic woes that caused the region to decline in recent years, the Midwest found itself on the receiving end of a steady flow of cultural disdain, whose principal target was that characteristic Midwestern settlement, the small town. “The Revolt from the Village” was the name given this literary and cultural moment by Carl Van Doren in his 1921 study, The American Novel, and examples of his thesis were plentiful and close at hand. Edgar Lee Masters’s 1915 book, Spoon River Anthology, a collection of autobiographical epitaphs from a small-town cemetery, evoked the acrid hypocrisy and repression of the small-town environment. Similarly, Sherwood Anderson’s Winesburg, Ohio (1919) sought to uncover what Van Doren called the “buried and pitiful” lives of its inhabitants. Ernest Hemingway complained of his childhood home, Oak Park, Illinois, that it was a place with “broad lawns and narrow minds.”

But the master of the genre was Sinclair Lewis, America’s first Nobel Laureate in Literature, whose Main Street (1920) depicted the life of Gopher Prairie, Minnesota, in bitterly mocking tones:

This is America—a town of a few thousand, in a region of wheat and corn and dairies and little groves.The town is, in our tale, called “Gopher Prairie, Minnesota.” But its Main Street is the continuation of Main Streets everywhere….Main Street is the climax of civilization. That this Ford car might stand in front of the Bon Ton Store, Hannibal invaded Rome and Erasmus wrote in Oxford cloisters. What Ole Jenson the grocer says to Ezra Stowbody the banker is the new law for London, Prague, and the unprofitable isles of the sea; whatsoever Ezra does not know and sanction, that thing is heresy, worthless for knowing and wicked to consider.Our railway station is the final aspiration of architecture. Sam Clark’s annual hardware turnover is the envy of the four counties which constitute God’s Country. In the sensitive art of the Rosebud Movie Palace there is a Message, and humor strictly moral.

Two additional facts: Main Street was the bestselling work of fiction in the United States in 1921. It also was banned at the public library of Alexandria, Minnesota.