The Metaxy: A Primer

Christianity says life is hard because of Original Sin.

Eric Voegelin would say it's hard because we live in the metaxy.

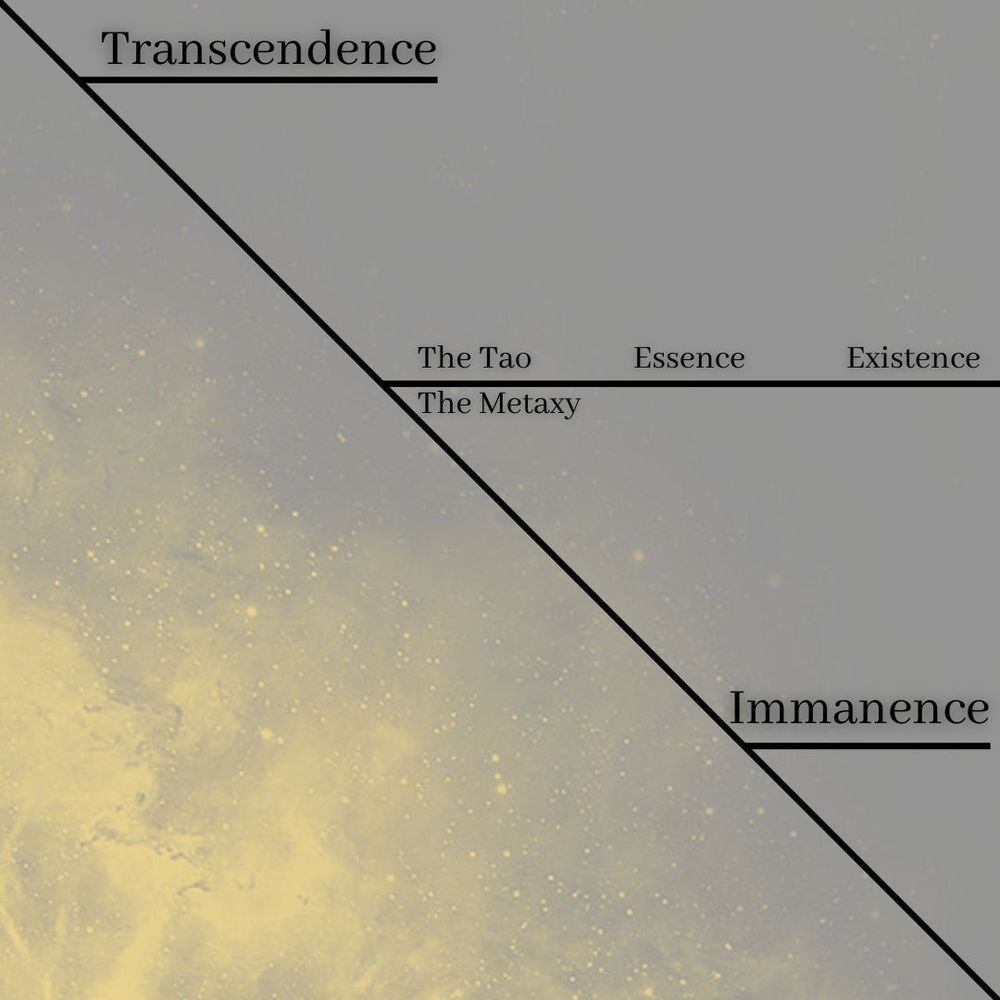

METAXY: The permanent in-between structure of existence. Sometimes referred to as the between or in-between, meaning that humans live in a structure of reality that is between the poles of existence. Michael P. Federici, Eric Voegelin.

The important points here are the "poles" and "in-between." We exist between lower and upper: transcendence--immanence, perfection--imperfection, omniscience--ignorance.

We not only exist between the poles, we participate in each pole. We are pulled toward each pole.

The result: tension.

The tension of existence: of living in the metaxy.

Some feel the tension more strongly than others. Artists, for instance. Maybe drunks. And saints.

The tension makes life hard but it also makes life worth living. It's why we get up in the morning; it's why we do the right thing . . . heck, it's why we even believe there is a "right thing," even if we can't always define or explain it, which is often because the transcendent pole is, well, transcendent: it surpasses our earthly modes of logic and language. All we can do is try to bridge the gap by accepting the gap (the metaxy), thereby bringing the transcendent and immanent together in the only creature meant to exist in both: humans.

Since we're meant to exist between the poles, the tension, though hard, also makes us healthy. When we engage with both poles of existence, we flourish. The best things in life are neither material nor spiritual: they're both, because both poles combine to give us a taste of full reality. Christians often refer to this as a "sacramental view" of reality: matter and spirit in one.

Historically, Awareness of the Metaxy Unfolded in Leaps

Humans haven't always recognized the metaxy. Our awareness of it unfolded gradually over the millennia.

It took a big step forward with the Israelites and the notion of a transcendent god who, for some reason, cares about humans. It also took a big step forward during a thing that Charles Taylor called “The Great Disembedding.” Karl Jaspers called it “The Axial Age.” Arthur Koestler called it “that tremendous century of awakening.”

People were beginning to realize they had souls that needed to be attuned to transcendence. This, in turn, shifted their relationship with their neighbors.

It was a major positive development.

But there was also a major "growing pain" development around the same time: The coming of ecumenic empires.

With the coming of the Assyrian Empire, followed by the Babylonian, then the Persian, then the Greek, then the Roman, old cultures were crushed. And with them, their gods and cosmology.

Ecumenic empires displaced people. Your neighbor no longer spoke or even looked like you. He worshipped different gods and looked at things differently.

The ecumenic empires, to borrow a current phrase, threw everyone's cosmologies into the free market of ideas.

In the resulting milieu, the old gods and cosmologies, which were "compact," scarcely recognizing a gap between transcendence and immanence (think "totem poles" and "Zeus banging teenage girls"), were torn open and shown to be false.

No longer did people stand with both feet--and their heads and hearts and hands--in the dirt.

They stood on the dirt and stretched toward the clouds. They were aware that they were living in the metaxy.

Awareness of the Metaxy is Wonderful but Also Difficult

It's obviously a much better existential state of affairs.

But it has costs.

Specifically, such awareness is a stretch.

The tension of a stretch feels great: you loosen tightened muscles and connective tissues. But it also kinda hurts.

And sometimes, the stretch gets so intense, things snap or you lose your balance.

Although it feels better and safer to live in one's existentially compact pagan communities, it's a pitiful existence compared to the liberating existence of the metaxy.

But the tension of the metaxy has significant risks.

When people can't handle the tension, they snap or lose their balance.

Picture a chain snapping when a truck is trying to pull a car out of the ditch. Picture a Jenga tower crashing when the wrong piece is pulled out.

That's what happens when a person doesn't deal with the tension properly.

Gnosticism Arrived with the Metaxic Leaps in Awareness

It's no coincidence that the first historical accounts of the phenomenon known as "gnosticism" started with the rise of the ecumenic empires and hit full stride with the first religious character to plunge humanity headlong into the metaxy: Jesus Christ.

Gnosticism is what happens when a person fails to deal with life in the metaxy.

I can't use this piece to explore gnosticism, but I've written a lot about it.

For now, I only want to emphasize that the gnostic deals with the metaxic discomfort by lopping off one of the poles of existence. He lops off the immanent pole (the existential mistake of the ancient gnostic) or he lops off the transcendent pole (the existential mistake of the modern gnostic). The relief is the same: by lopping off one pole, the tension is eliminated.

Either way, the person finds himself existing and trying to make sense of a fundamentally flawed reality. He still has all his faculties--in particular, his intelligence, logic, and rationality--but everything he does or thinks starts from a flawed reality, resulting in bad conclusions.

Sometimes, the results are catastrophic, like the murder of millions by the Communists and Fascists. Sometimes, they're tragic, like the suicide of one poor guy who can't make sense of existence.

Communists and Fascists are hardcore gnostics. They check every box on Eric Voegelin's list of six gnostic traits.

The suicide barely qualifies as a gnostic because, although he has a pitiful sense of existence like the gnostic, he doesn't try to force it on others.

That's something that I think is crucial to understand. Gnosticism isn't a binary disorder: you're gnostic or you're not. It's a spectrum disorder. On a scale of one to ten, the Communists are a "ten." The suicide is probably just a "one."

I'll explore gnosticism as a spectrum disorder in later pieces.