The Left Hemisphere Larps

The response that I featured in yesterday's post used the word "LARPing." I'm embarrassed to admit: I didn't know what it means. Fortunately, I have a Google machine (well, I've started using the Perplexity machine . . . an incredible AI tool recommended at my annual estate law conference last month). Per Perplexity:

LARP stands for Live Action Role-Playing, which is an interactive form of role-playing game where participants physically portray their characters and act out scenarios in a fictional setting. It involves dressing up in costumes, using props, and enacting the roles through physical actions and interactions with other players.LARPs can take place in various genres like fantasy, science fiction, historical settings, or modern-day scenarios. The participants pursue goals and objectives within the game's narrative while adhering to predetermined rules or reaching consensus on outcomes. LARPs can range from small private events lasting a few hours to large public events with thousands of players spanning multiple days.

LARP is a fun fantasy thing: participants adopt a fake persona and play it out.

Now shift back to yesterday's criticism. "Shitlibs" in their secluded lives (Ivy towers) romanticize aspects of poverty (here, noisy neighborhoods) that the people who live in those neighborhoods want to escape. No matter to the shitlibs: they have idealized notion and they'll write narrative to fit that notion.

It's a characteristic of the left hemisphere.

Subscribers to Outside the Modern Limits and others might remember my admonition last December: don't let your left hemisphere ruin Christmas, which I summarize here,

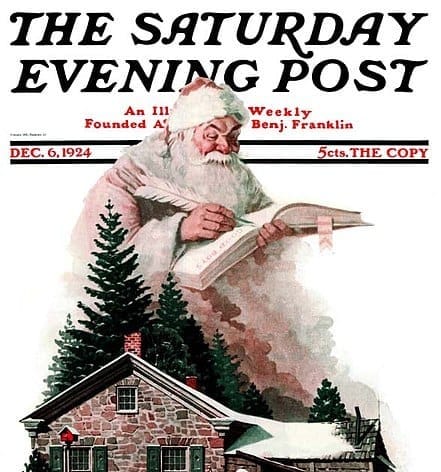

You have this idealized Rockwell notion of what Christmas will be like. Your left hemisphere loves such ideals (they make navigation in life a lot simpler, if far more ham-handed, clumsy, inartful, and ugly). It erects them and follows them. But then things don't turn out the way they've been idealized, and we get frustrated and angry (two left-hemispheric traits . . . McGilchrist calls anger the "most highly characteristic" emotional trait of the L.H.). If you do that with Christmas, you ruin it because you get frustrated or angry when things don't go that way . . . and they never do. Reality always intervenes.

When you're sitting there on December 15th, envisioning yourself standing in your Norman Rockwellesque family room, chatting (oh so) charmingly while sipping a cup of mulled wine while the toddlers chirp happily in the next room, you're LARPing.

And then it doesn't work out. You spill the mulled wine on your white carpet. The person you're talking with has the attention span of a toddler. The toddlers aren't chirping: they're screaming, hitting, not staying in the next room, and despoiling your white carpet in every imaginable way.

Reality beats the hell out of the Norman Rockwell ideal every time, and if your left hemisphere stays committed to the Rockwell, things get ugly . . . fast.

It's like that with all left-hemispheric notions that get elevated. The left hemisphere needs broad principles to guide its everyday actions, but it needs to keep them in check: it needs to make sure they remain expedients for action, not get elevated to ideals or, worse, get apotheosized into logocentric ideas that trump everything else.

Joe Rogan likes to observe, "Hold your opinions. Don't let your opinions hold you."

That's what I'm talking about. The left hemisphere strongly inclines toward opinions because it needs to make a lot of decisions. Decisions are merely opinions writ small: micro-opinions. We constantly form micro-opinions throughout the day.

Micro-opinions (decisions) are like principles: they guide day-to-day actions. We need decisions (micro-opinions) and we need principles.

"Hold principles. Don't let your principles hold you." Put another way, "Hold principles, but don't elevate them into ideals."

And how do you know you've elevated a principle into an ideal? I'd say it's when you write an essay that celebrates your ideal even though it clashes with reality. An essay like the one celebrating noise in poverty-stricken neighborhoods is the intellectual or civilized parallel of throwing your cup of mulled wine against the wall when everything about Christmas gets shat upon by reality. When you spend hours writing an essay based wholly on a fiction, or when you throw a tantrum at Christmas, you're showing clear signs that you've elevated a principle or notion into an ideal abstraction that prevails, for you, over reality. The essay is a fraud; the angry person is an ass. Both are products of the left hemisphere.

The thing is (possibly the most troubling thing), the essay doesn't feel fraudulent to the essayist and fans of The Atlantic because it fits the ideal they have in their heads, just as the foiled Norman-Rockwellite is completely serious when he storms out of the room and announces he'll be spending next year's holiday on a Caribbean cruise.