The Gnostic Never Blames Himself

Part II of an Analysis of Eric Voegelin's Six Gnostic Traits

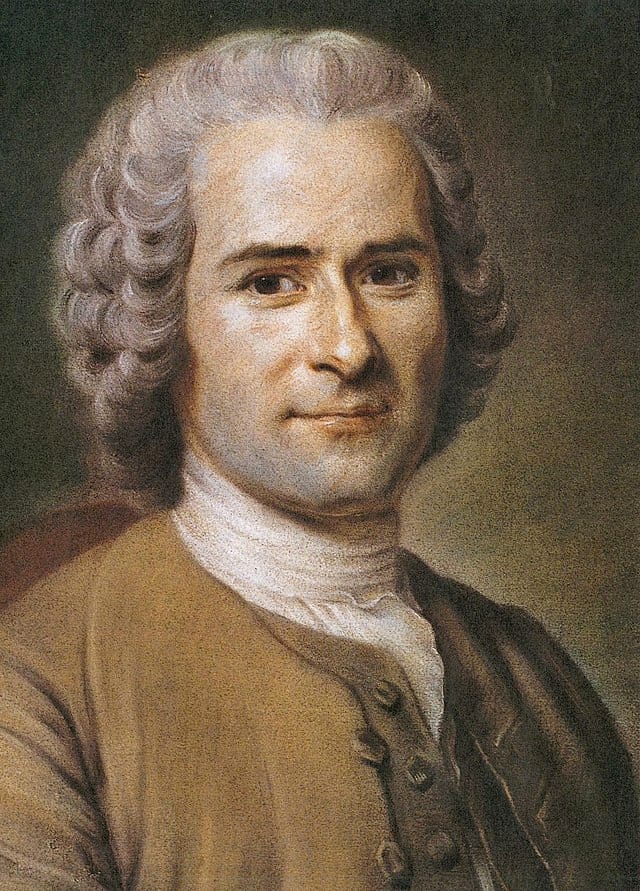

“Man is born free and everywhere he is in chains.” Rousseau

Rousseau’s passage from the beginning of The Social Contract contends for the most famous in philosophy.

Rousseau’s point was simple: Humans are good, but there’s a lot of suffering, so social institutions must be corrupting everything.

Significantly, Rousseau didn’t see any problems with himself. He was arguably the most self-centered philosopher of all time. He was so self-centered, biographers wonder if he was even capable of love. He said of his long-time mistress, a lowly laundress that he,

Never felt the lease glimmering of love for her . . . the sensual needs I satisfied with her were purely sexual.

When those sensual needs resulted in five children, he put them into orphanages, which, given the state of orphanages in the 18thcentury, was practically a sentence of torture and early death: only five percent of orphan children survived to adulthood, and most of the adult survivors became beggars and vagabonds.

His delusions of grandeur were incredible. After he condescended to marry the laundry woman after 25 years, he toasted himself and told everyone that posterity would erect statues to him and “It will then be no empty honor to have been a friend of Jean-Jacques Rousseau.”[1]

He was, to be blunt, a first-rate ass.

But it never seemed to have crossed his mind that suffering exists because of people like him. He imposed cruel sentences on his children, but it wasn’t him. It was society’s fault.

The Gnostic Never Blames Himself

Such is Voegelin’s second trait of the gnostic:

[T]he second aspect of the gnostic attitude: the belief that the drawbacks of the situation can be attributed to the fact that the world is intrinsically poorly organized. For it is likewise possible to assume that the order of being as it is given to us men (wherever its origin is to be sought) is good and that it is we human beings who are inadequate. But gnostics are not inclined to discover that human beings in general and they themselves in particular are inadequate. If in a given situation something is not as it should be, then the fault is to be found in the wickedness of the world.

The Gnostic Rejection of Reality Takes Three Forms

Rousseau rejected reality by believing that the social institutions (that had risen organically over the course of thousands of years) are illegitimate. That’s one form of the gnostic rejection of reality.

This gnostic rejection of reality takes at least two other forms.

1. Belief that the earth is illegitimate: an illusion, a trap or prison.

2. Belief that the transcendent isn’t legitimate: an illusion, a con or drug.

Ancient Gnostics Believed the Earth Isn’t Legitimate

Sperm cults, orgies, free love, gluttony. Such things were permitted to the ancient gnostics.

The accounts of their decadence are almost unbelievable . . . literally. We only have their Christian opponents’ accounts, which are probably exaggerated.

But if only half of the stuff is true, wow.

The ancient gnostic’s logic worked like this: An evil god made this world. Therefore, everything in the world is illegitimate. The gnostic is a wholly spiritual being. Therefore, nothing in the world can defile him and he can do whatever he wants.

It’s a perennial phenomenon. It happened in the Middle Ages; it happened in the 1960s hippy culture.

A good ancient gnostic is not merely permitted to do what he wants. He’s expected to, in order to show that he’s one of the spiritual ones who isn’t affected by earthly matter. Indeed, in the ancient gnostic system, he becomes obligated to. It’s a rite of passage. Christians renounce the devil through sacramental rituals. The ancient gnostics renounced the world through orgiastic rituals.[2]

The principle that the world is the creation of an evil god, however, can also result in asceticism: severe asceticism in the attempt not to indulge any element of it, much like people back then refused to come near a leper.[3]

You can see the same phenomenon among Hindu ascetics who renounce the world because they deem it an entrapping illusion (maya). They would kill themselves, but that would be an act of the will, which would merely be another act within the illusion. Instead, their most advanced adepts wade into the Ganges River and accept death by crocodile.

The Modern Gnostic Believes the Transcendent Isn’t Legitimate

This is the Promethean. I’ve already addressed it extensively here and here. It’s the belief that the divine order sucks. It’s either stupid (Prometheus’ view of Zeus) or illegitimate (without his help, Prometheus believed, Zeus wouldn’t be Zeus) or simply nonexistent.

No matter the form, it centers on one thing: Hatred of the gods and revolt against them . . . and the traditions, norms, and organic growth over the centuries that emanated from them.

Eric Voegelin said this type of “pneumapathological consciousness can be found, in varying degrees of prominence, in virtually every moment of note within modern political thought.”[4]

Anarchism

Behaviorism

Biologism

Constitutionalism

Existentialism

Fascism

Hegelianism

Liberalism

Marxism

Positivism

Progressivism

Psychologism

Scientism

Utilitarianism

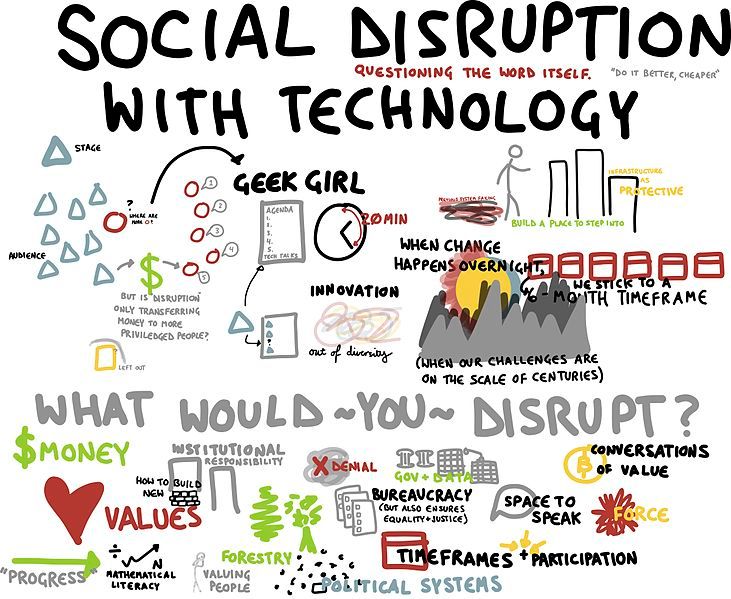

The Gnostic Revels in the Disruptive

A gnostic might reject societal norms like Rousseau. He might reject creation like the ancient gnostic. She might reject the transcendent, like Prometheus and the modern gnostic.

All three forms celebrate disruption. The gnostic likes to shake things up. He strives to be jarring.

I have little doubt that much of it stems from simple pride. The gnostic doesn’t want to be just another person. The gnostic wants to be elite or at least part of an elite group. That’s why he cherishes the special knowledge that is the core of gnosticism (which we’ll address when we get to Trait 6).

But this love for disruption is more profound than mere vanity, though the profound aspects are wrapped in vanity.

The gnostic rejects reality as given. He doesn’t want reality as it has been laid out in his culture over the course of thousands of years. This means he doesn’t want anything that is soaked in that reality, including its traditions, norms, and institutions.

Especially its institutions.

So the gnostic attacks the institutions . . . always.[5]And also traditions and norms.

Such things don’t comport with the way the gnostic sees (wants) them to be, so he tears at them. Distrust, rejection, and destruction of institutions become implicit in everything he thinks and does. It becomes his default mode of thought and action.

I once had a priest who reveled in “shaking things up.” He never wanted people to be comfortable. It doesn’t mean he was a gnostic (all six traits, remember, must be hit), but he was an ass.

And so is the gnostic.

The gnostic’s desire to disrupt things emanates from his pride. Why accept things as given when the gnostic has better rational ideas that should control?

Pride is the essence of an ass.

Rousseau was an Ass

Go back to Rousseau. He was one of those guys, I believe, who drove himself to insanity with his arrogance,[6]much like Prometheus going writhingly mad on that rock.

He was a great stylist in a culture that valued letters, so people wanted to be his friend, but he was incapable of friendship, such was his self-centeredness. When Rousseau claimed to be a literary martyr in France, Hume brought him to England and gave him a hero’s welcome, treating him practically like royalty, but Rousseau became convinced that Hume was part of a plot to persecute him further, quarreled with Hume (a man hardly given to quarreling), and went back to France.

One modern academic said Rousseau was a

masochist, exhibitionist, neurasthenic, hypochondriac, onanist, latent homosexual afflicted by the typical urge for repeated displacements, incapable of normal or parental affection, incipient paranoiac, narcissistic introvert rendered unsocial by his illness, filled with guilt feelings, pathologically timid, a kleptomaniac, infantilist, irritable and miserly.[7]

He was, in short, a maniac.

And so is the gnostic.

Ass and maniac. That's the gnostic.

[1]Paul Johnson, Intellectuals (Harper, 1990), 19-21.

[2]See Hans Jonas, The Gnostic Religion (Beacon, 1963), 273.

[3]See Kurt Rudolph, Gnosis: The Nature and History of Gnosticism (Harper, 1987), 248-259.

[4]Michael Franz, Eric Voegelin and the Politics of Spiritual Revolt (LSU, 1992), 8.

[5]See Eric Voegelin’s account of Puritanism in The New Science of Politics(University of Chicago, 1987), 133-161.

[6]But he also had troubles with a deformed penis, which probably didn’t help matters. Johnson, 9.

[7]Johnson, 26.