When the World First Started to be Aware of Transcendence

Ten of History's Greatest Seers All Lived Around the Same Time

Something lit up humanity around 500 BC.

Charles Taylor called it “The Great Disembedding.” Karl Jaspers called it “The Axial Age.” Arthur Koestler called it “that tremendous century of awakening.”

About this time, philosophers, mystics, and religious thinkers throughout the world (the “500 BC Seers”) came to realize that reality consists of two levels: heaven and earth (transcendence and immanence). They taught their followers that each person has an individual soul that should be open to the divine.

It was a social thing

It wasn’t just a religious thing. It was also a social thing.

It told people they had relevance beyond their group. Regardless of a person’s position in the tribe, he had relevance as a creature of the divine.

It was huge. Existence was no longer seen as a single cosmos, where natural occurrences were synonymous with magical ones, community life was religious life, and earthly rulers were seen as gods. Existence was no longer “compact,” to use the term favored by Eric Voegelin.

Existence, under the guidance of the 500 BC Seers, became differentiated. Earth-Heaven: Related. But not the same. Two elements of one reality, but distinct, different, elements.

This newfound awareness would morph, develop, and evolve throughout world history and eventually find itself embedded in the U.S. Constitution and its counsel that government and religion should be separate.

The 500 BC Seers

Scholars have disagreed about the era’s span. Karl Jaspers said it spanned from 800 BC to 200 BC. Others have narrowed the span. Voegelin extended it to include the advent of Christianity.

But all seem to agree that the core irruption occurred in the 500s BC. Say, 600-450 BC.

The Deutero-Isaiah

The prophets present the biggest problem with the 600-450 BC dating. Most of the great ones came before 600.

But there were a few in this area, most notably, Jeremiah and Ezekiel.

Most significantly, this era saw the Babylonian Exile, in which much of the population of Judah was carted off to live in Babylonia in 589 BC. While there, Judaism as a religion flourished. It was the first time that a religion existed independent of an earthly realm to support it. It was arguably the definitive “break” with the cosmologically-compact view of existence that dominated prior to 600.

This era also produced a poet known as “Deutero-Isaiah,” who wrote Isaiah chapters 40-55, which is arguably the pinnacle of the Old Testament. No one knows for sure when it was written, but most agree it was probably near the end of the Babylonian Exile (which ended gradually around 530 BC).

Confucius

He wrote nothing. He was an aggregator: of Chinese tradition. He used it to teach a new humanism. He believed people could be good but they needed to live in a society that respected them as persons with God-given rights, who needed to be educated in the sacred. Heaven is “up there,” yes, but individual souls need to be opened to it. Mencius, a lesser 500 BC Seer, was his disciple.

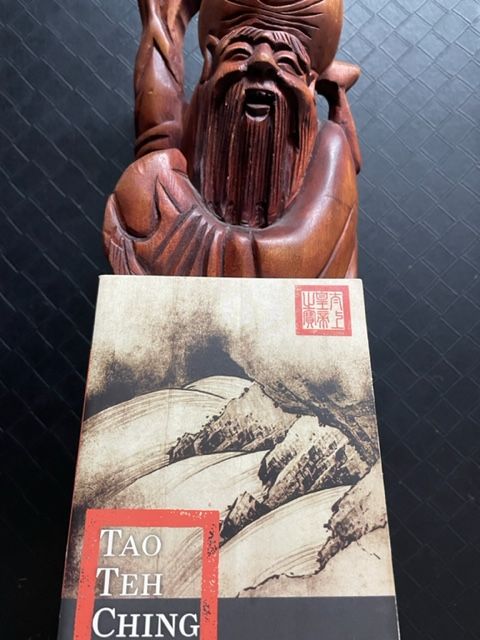

Lao-Tzu

This semi-legendary founder of Taoism mounted a water buffalo at the end of his life and rode off to the western boundary of China. There, legend tells us, a farmer recognized him and asked him to write down his philosophy of life. The result: The Tao Teh Ching, a book filled with thoughts (or non-thoughts) about trying (or not trying) to live in the Tao. It’s the perfect accompaniment to his act of turning his back on the world by mounting that water buffalo in the first place.

The Upanishads

These are the basic philosophical texts of Hinduism. Hinduism developed a troubling nihilism, a philosophy of despair that thinks paradise (moksha) is attained through annihilation, but these texts reveal so much philosophical subtlety, it’s hard to believe came from the primitive civilization where they originated. Many of them pre-date 600 BC, but they culminated near 500 BC

The Mahavira

Founder of Jainism, according to western scholars, though the Jains claim he was the last of a long series of “Tirthankaras,” which descended from pre-historical times. This founder of one of the three major religions of India (Hinduism and Buddhism are the other two) was a contemporary of the Buddha.

Gautama Buddha

A prince. His king father was told he could become a great king or a buddha. His father wanted him to become a great king so he kept him sheltered through his young adult life, living in luxury, insulated from harsh reality. But at age 29, Siddhartha went outside the palace and saw an old man, a sick man, and a dead man. He was rattled. He then saw an ascetic and resolved he must find a way out of suffering. He spent a prolonged time in meditation and emerged as the great Buddha, teaching that suffering is eliminated through the Noble Eightfold Path.

Pythagoras

A pioneer in geometry, yes, but mostly a mystical philosopher, who some credit with establishing the first contemplative monastery. His interest in math was merely an outgrowth of his interest in eternity. Numbers are eternal; everything else perishes. Geometry was ecstasy: it purges the soul of earthly passion and is the principal link between man and divinity. He also used music to purge the soul.

Heraclitus

All is change. You never step into the same river twice. All is fire. A mystic who hated superstition. This enigmatic thinker deposited his great work in the Temple of Artemis in Ephesus so it wouldn’t get into the hands of the unwashed masses. Only fragments survive.

Thales

The father of philosophy and one of the Seven Sages of Ancient Greece. He looked for the one unifying element of this puzzling world and concluded it is water.

Parmenides

Jacques Maritain called him the “slave of being.” Through rigorous logic, he established that all is being: a completely one, absolute, immutable, eternal, incorruptible, indivisible, whole and entire unity that encompasses all and is perfect. Being is so total, no other beings can exist and there can be no change.

The contrary conclusions of Heraclitus (all is change) and Parmenides (change is impossible) vexed thinkers for centuries until Aristotle thought us out of it through his four causes.

But now I’m beyond the 500 BC Seers.

Further Reading

Eric Voegelin, The New Science of Politics and The Ecumenic Age

Heinrich Zimmer, Philosophies of India

Arthur Koestler, The Sleepwalkers

Jacques Maritain, An Introduction to Philosophy

Henry Veatch, Aristotle: A Contemporary Appreciation