The Doors Don't Open on Madison Avenue

Christopher Sandford at The Spectator

The once-explosive accusation that a rock ’n’ roll band is a sell-out, aimed at artists who make an accommodation with industry, has come to seem a little naive since it was first bandied about in the 1960s. Whether it’s that well-known monument to prudence Iggy Pop extolling the virtues of car insurance, the Zombies promoting Tampax or Bob Dylan shilling for Victoria’s Secret, they’re all at it these days. Elton John wants you to dial UberEats, the Stones will start you up with a $139.99 Keurig coffee machine, and by now it might be easier to list the names of rock stars who haven’t chugged Pepsi on TV than those who have. And you’d have to go even further back than the Sixties — Shakespeare’s “Sonnet 110,” in fact — to find the definitive lament about the corrupting marriage of art and finance:

Alas! 'tis true, I have gone here and there

And made myself a motley to the view,

Gored mine own thoughts, sold cheap

what is most dear,

Made old offenses of affections new.

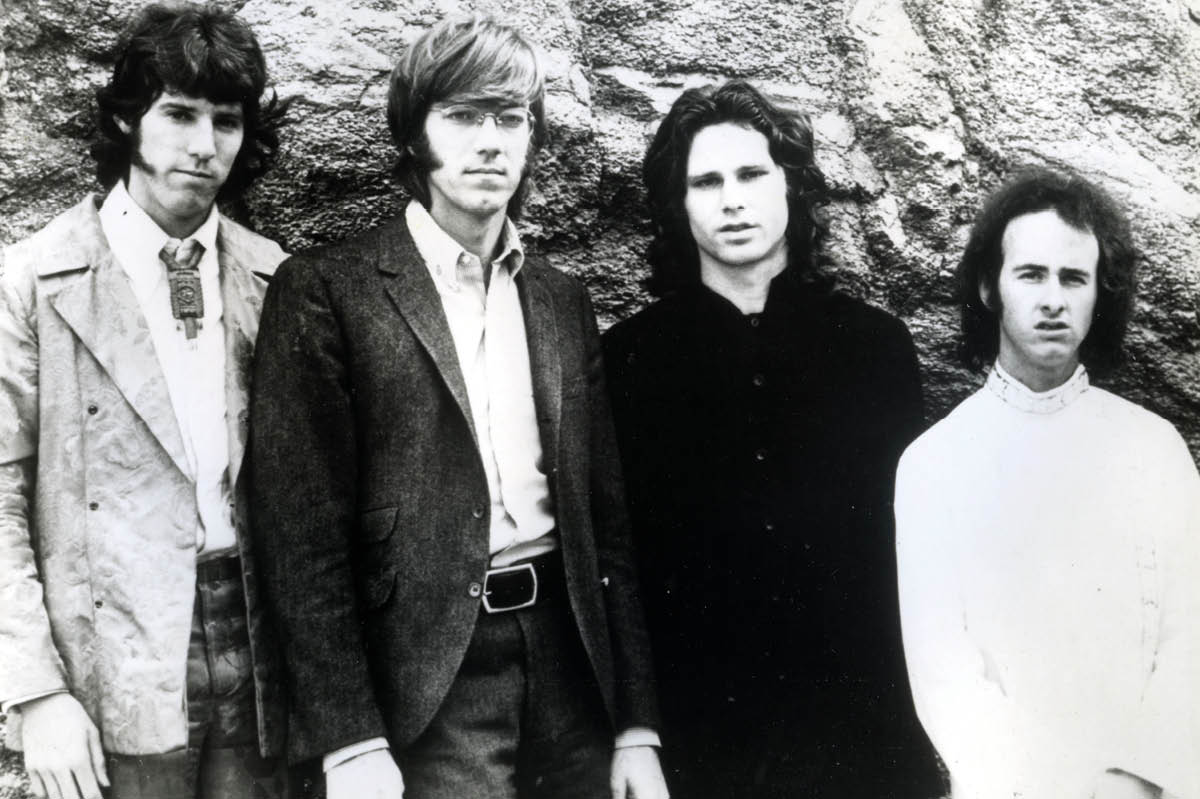

All of which brings us to the strange case of the Doors’ drummer John Densmore and his protracted legal battle against his former workmates about their appropriation of the band’s name. You may remember the group: in addition to the superbly proficient Densmore, there were the cloudy-haired Robby Krieger and Ray Manzarek, looking like a hip chemistry professor, on guitar and keyboards respectively; and up front, Jim Morrison, at least in the early days a pop Adonis in leather pants and silver concho belt, with a baritone howl that sounded like Frank Sinatra on quite a lot of acid. Between them they specialized in not so much songs as in edgy sonic pastiches like “Riders on the Storm,” “Strange Days” and the twelve-minute psychodrama of droning fairground organ, hypnotic drums and disturbing vocal interjections they called “The End.” Morrison died in July 1971, officially of a heart attack, although as usual on these occasions hardcore fans continue to insist that the real cause of their hero’s demise lies buried somewhere back among the chaos of his twenty-seven years alive, or for that matter that he faked the whole thing and is even now residing among the Navajo of rural Arizona.

“There was Jim, the wildly creative guy who couldn’t play a note of music but who heard whole concerts of stuff in his head,” says Densmore, still exasperated by the thought more than half a century later. “And then there was this other character I called Jimbo, a kamikaze drunk who came close to squandering the whole thing by behaving like a Skid Row bum.” Morrison always had a penchant for confronting his audience, but toward the end he seemed to be increasingly channeling his inner Benny Hill by shedding his trousers onstage or telling excruciating jokes about a blind man confusing a fish for his girlfriend. Some of his other concert repartee was even less elevated.

“We got to our final show at New Orleans in December 1970,” Densmore remembers. “It was a full-on Jimbo performance. He was cracking terrible jokes, rambling on as the three of us tried to get a song started. You could hear the audience groaning. Finally, I counted in ‘Break On Through,’ and we somehow fumbled through the rest of the set. It was a total embarrassment, and later I just turned to Robby and Ray and said, ‘That’s it. We’re not going out on the road with that lunatic again.’ Nowadays you’d try and get him into therapy. I’m sure Jim could have cleaned up with professional help. Why not? He was a smart guy. But we badly needed a break.”

Densmore wasn’t alone in his conviction, because just three months later Morrison left for Paris in an attempt to write poetry, address his health issues and generally decompress.

Read the rest (subscription may be required)