The Conservative Abandonment of Culture

Jason Jewell at Law & Liberty

Since Donald Trump shook up the American Right in 2015, many books and manifestos about the conservative movement and its future have appeared. Most of these works seek to stake out positions on familiar political and economic questions. Revisionists such as Julius Krein have called for an industrial policy to replace America’s free-trade orientation. Others like Adrian Vermeule counsel a move away from originalism as a governing judicial philosophy. The signatories of First Things magazine’s “Against the Dead Consensus” want immigration restriction, pro-worker legislation, and other policies they believe would strengthen the American family. For their part, defenders of more open markets, like Donald Devine and Samuel Gregg, deny that there is anything fundamentally wrong in these policy areas and that conservatives should reject calls for radical changes.

Claes Ryn appears to think that all these debates are beside the point and that these authors are whistling past the graveyard. Now a Professor Emeritus of Politics at the Catholic University of America, Ryn has critiqued the prevailing winds in American conservatism for decades in books such as The New Jacobinism (1991), America the Virtuous (2003), and A Common Human Ground (2003). Now, in The Failure of American Conservatism and the Road not Taken, readers will find a collection of Ryn’s previously published essays along with roughly seventy pages of new material intended to structure the collection. Together they form a bracing introduction to Ryn’s corpus for those unfamiliar with it and a useful compendium for others who have appreciated his contributions to the debates over conservatism in recent decades.

Following the introductory section of newly composed material, we find more than 350 pages of previously published essays, articles, and book excerpts. These are divided into five sections: “America’s Divided Self,” “The Constitution and Its Enemies,” “Challenges and Fissures,” “The Great Neglected Power,” and “In the Eleventh Hour.” The titles give some indication of the ideas treated in each, but the nature of the collection means that the division of topics among sections is neither neat nor tidy. Readers should use the selections’ titles and Ryn’s short introductory comments at the beginning of each piece to guide them to the material they will find most interesting or useful.

Several important criticisms of postwar conservatism first surface in the Introduction and then recur throughout the collection. Focusing on them here might be the most helpful way to explain the book’s significance.

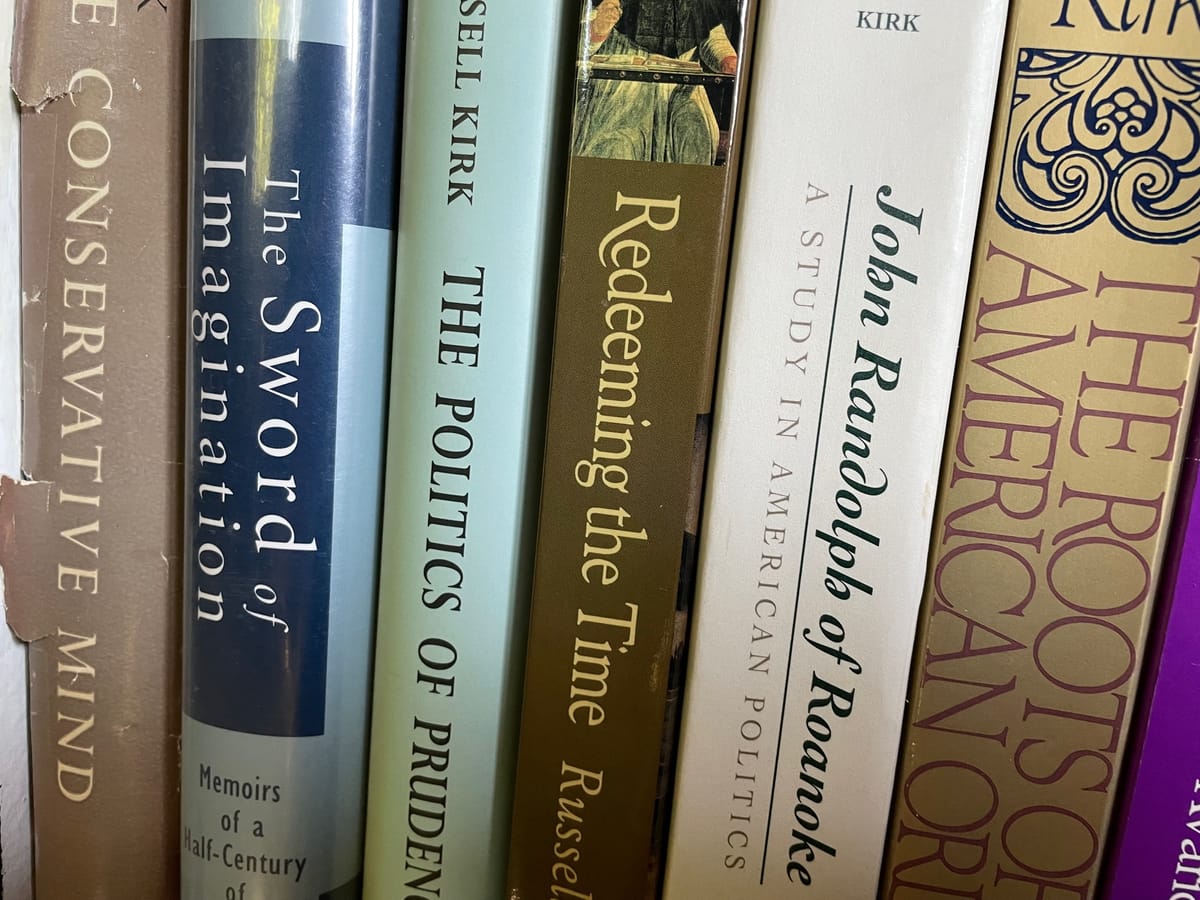

Ryn believes that the postwar intellectual conservative movement began with great promise in that several of its most prominent figures were serious proponents of high culture. Among these were Russell Kirk and Peter Viereck, two history professors with a strong literary bent. Kirk wrote critical essays, short stories, novels, and a monograph on T. S. Eliot in addition to his historical writings and books on Anglo-American political thought. Similarly, Viereck wrote fiction and won a Pulitzer Prize for poetry in addition to his work on history and politics.

However, Ryn argues that a “powerful utilitarian bias” in the movement relegated these figures and others like them to the margins by the mid-1960s in favor of a focus on economics, business, and practical politics. This choice was a strategic error because electoral and policy victories could not check or reverse the eroding of America’s moral and cultural foundations. Conservatives today tend to have “unmusical personalities” and “feel no deep existential need for poetry, novels, paintings, symphonies, films, and such.” But by ceding to the Left, literature, the arts, and culture more generally—the fields that shape society’s moral vision—conservatives unwittingly opened the door to woke capitalism and cancel culture.

Anyone looking at the survey data of university faculty and practitioners of the arts and humanities would be hard-pressed to refute Ryn’s contention that the conservative movement has neglected these fields in relative terms. My own firsthand observations confirm this. Over the past decade, I have attended several dozen conferences and other events organized and hosted by conservative institutions. At probably 90% of these gatherings, lawyers, economists, and policy wonks make up the vast majority of attendees. Many, if not most of these people, are products of discipline-specific fellowship and degree programs developed and funded by conservatives over the past several decades. By contrast, writers of imaginative literature, philosophers, historians, and artists—disciplines toward which little or no movement funding is targeted—are few and far between.

This disdain for “merely” cultural concerns, writes Ryn, led conservatives to neglect “perhaps the most powerful and prophetic American thinker of the twentieth century,” Irving Babbitt (1865–1933). Throughout the book, Ryn echoes many of the arguments that this leader of the “New Humanists” of the early twentieth century developed in books such as Literature and the American College and Democracy and Leadership. Perhaps the chief among these is the insistence that moral virtue consists of carefully cultivated habits and deliberate, rational acts of the will rather than the “idyllic imagination” of figures like Jean-Jacques Rousseau and a naive reliance on the supposed innate goodness of humanity. Ryn sees Babbitt as having prophetically warned of the “destructive sham spirituality” characteristic of Progressivism that came to redefine public virtue in the twentieth century. This transformation of the Western imagination downplayed or repudiated outright the need for self-discipline and restraint and instead located the causes of societal problems “somewhere out there” to be addressed by social reformers.