The Zen of Littleness: St. Therese's Way

Dogen, the father of the Soto School of Japanese Zen, is arguably the most significant intellectual in the Zen tradition.

As a young man in 1223, he sailed to China, but his ship couldn't land until it got clearance. It was stuck off-shore for three months.

One day, a Chinese cook came on board to buy shiitake mushrooms from the Japanese. Dogen talked with him and was impressed by his wisdom. Dogen wanted to talk longer, but the cook said he had to go back to work because it was his form of Zen practice.

Dogen, noting the cook’s advanced years, suggested the cook should instead devote himself to meditation and koans.

The cook laughed and said, “My good fellow from a foreign land, you do not yet know what practice means, nor do you yet understand words and scriptures,” then abruptly left.

When they met again, Dogen pressed him for answers. The cook replied with an absurd/unintelligible response.

The absurd words transformed Dogen, who wrote about it years later in The Lessons from the Monk-Cook.

Dogen said the old cook was a “man of the Tao” who showed Dogen how daily work that flows out of enlightenment is a religious practice.

The cook, Dogen explained, brought him to understand how any activity can be a Zen practice.

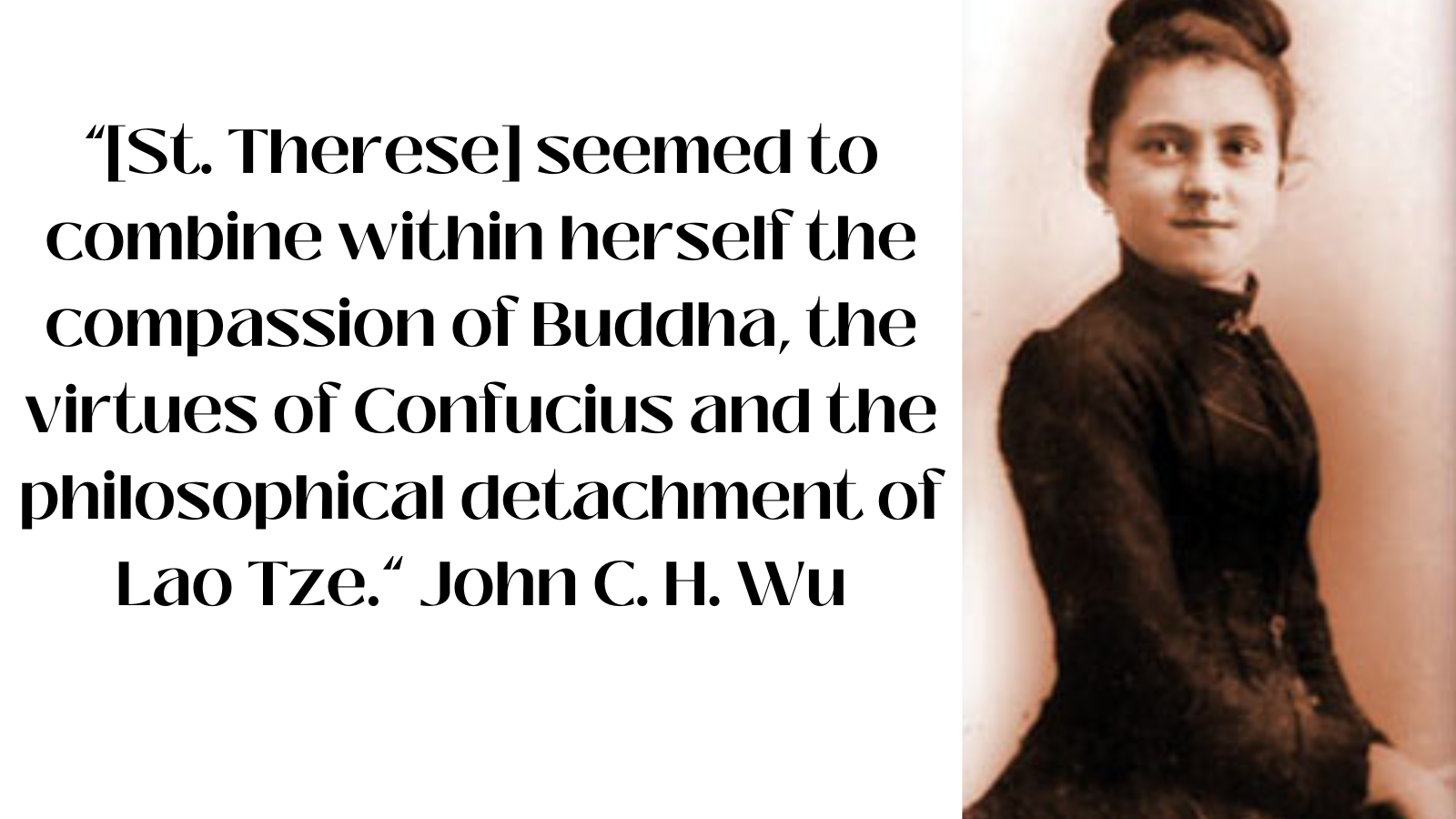

St. Therese's Little Way Parallel's Dogen's Cook

There are two exact parallels between Zen and St. Therese's Little Way.

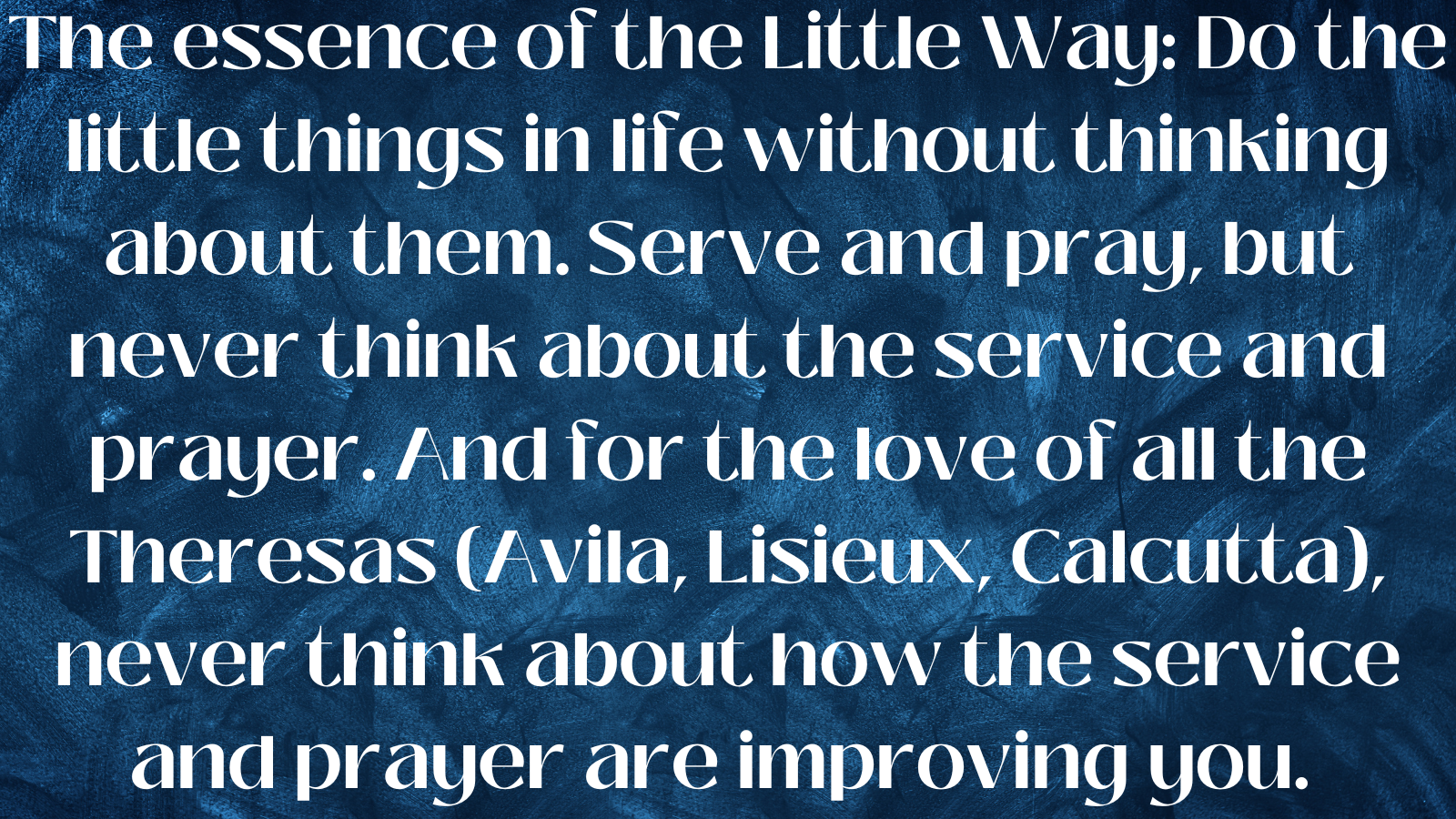

With neither The Little Way nor Zen is a person concerned about his spiritual life

According to Canon Paul Travert, late chaplain of the Carmel of Lisieux:

“For St. Therese there are no barriers before God: At whatever stage of the spiritual life the soul may be, whether still struggling against sin or advancing in the practice of virtue, there is but one thing to do: 'to surrender oneself more and more like a child to God's affectionate embrace.'”

Similarly, von Balthasar said St. Therese had a “deep distrust of making surveys and standing back to take her bearings. . .”.

Likewise, in Zen, there is no goal. The Zen adept becomes enlightened by understanding that he must simply exist with no thought of enlightenment or spiritual advancement. In the words of modern Zen master Shunryu Suzuki in Zen Mind, Beginner's Mind: “The points we emphasize are not the stage we attain . . . You may attain some particular stage, of course, but the spirit of your practice should not be based on an egoistic idea.”

Neither The Little Way nor Zen attaches much importance to surroundings.

All places are good for the pursuit of The Little Way or zazen (Buddhist meditation). Consider these two unrelated quotes from Thomas Merton (the first is from his 1967 book, Mystics and Zen Masters, the second from his 1948 book, Seven Storey Mountain):

What is required [by the Zen master] is not the ability to repeat some esoteric formula from a book . . . but actually to respond in a full and living manner to any 'thing,' a tree, a flower, a bird, or even an inanimate object, perhaps a very lowly one. Zen masters frequently took their examples from the monastery latrine, just to make sure the student should know how to 'accept' every aspect of ordinary life and not be blocked by the mania of dividing things into holy and unholy, noble and ignoble, valuable and valueless. When one attains to pure consciousness, everything has infinite value.

She became a saint, not by running away from the middle class, not by abjuring and despising and cursing the middle class, or the environment in which she had grown up: on the contrary, she clung to it in so far as one could cling to such a thing and be a good Carmelite. She kept everything that was bourgeois about her and was still not incompatible with her vocation . . . To her, it would have been incomprehensible that anyone should think these things were ugly or strange, and it never even occurred to her that she might be expected to give them up, or hate them, or curse them, or bury them under a pile of anathemas.

The cook just cooked. Therese just did laundry.

Attributes, qualities, jobs: none of it matters. It all falls away in the highest pursuit of Zen; it all falls away in the Little Way. All that matters is one's existence.

The Little Way resonated with western civilization, which had been increasingly starved of the Tao throughout modernity, hence millions of people bought her little autobiography.

And that's the third parallel with Zen: Both caught fire in the twentieth century. And both caught fire for the same reasons: they rejected the Great Rejection and showed people how to get back in touch with the Tao.

I'll discuss Zen's western popularity in a later essay.