Southern Life, Agrarian Vision: The Apprenticeship of Andrew Lytle

By Mark Malvasi at The Imaginative Conservative

Born in Mufreesboro, Tennessee on the day after Christmas in the second year of the twentieth century, Andrew Lytle came early to Alive in a sense of eternity.[1] Lytle entered a world of settled customs and enduring associations. The web of family and community defined his youth. His long intimacy with the soil recalled the human frailty and imperfection that it is the lot each man to bear. In mind and spirit Lytle was closer to the twelfth than to the twentieth century for, as he later wrote, he “knew the orderly return of the seasons” and “saw the natural in the supernatural.”[2] Such an existence, above all, reminded him that he was mortal, a creature made and not begotten, fated like all creatures to return to the dust and ashes from whence God had called him forth. “What a small fragment time is before things eternal,” he marveled.[3] Yet, by the 1930s, Lytle understood that his perspective was becoming old-fashioned. “The momentary man,” who led a transient, nomadic existence, who resided in the eternal present, and who, if he believed in anything, believed in the possibility of a heaven on earth, was the characteristic figure of the late Modern Age.[4] The moral and spiritual confusion that ensued from his ascendancy infected every aspect of life, from religion to politics, from economics to the arts. In the eternal struggle for order and truth, all was chaos.

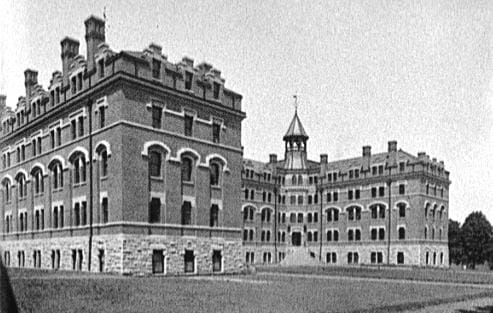

As his thought matured, Lytle turned increasingly to the history and culture of his native South to find an antidote for the ills of the modern world, though his recovery of the southern tradition was somewhat discursive. Three weeks after entering Exeter College, Oxford in 1921, Lytle returned to Tennessee upon the death of his maternal grandfather, John Nelson. To remain closer to his family, particularly his widowed grandmother, Molly, Lytle enrolled in Vanderbilt University, where he became a student of Donald Davidson and John Crowe Ransom and a classmate of Robert Penn Warren. While at Vanderbilt, Lytle attended some of the final gatherings of the Fugitive Poets, and published “Edward Graves” in the March 1925 issue of The Fugitive.[5]

In 1914, Ransom, along with Walter Clyde Curry, a colleague in the Department of English, had begun to meet informally with a group of undergraduates to discuss poetry and ideas. They frequently convened at the apartment of a local eccentric named Sidney Mttron Hirsch, who presided over the assembly from his chaise lounge. These relaxed conversations evolved into the regular meetings of the Fugitive Poets. American entry in the First World War dispersed the group, several of whom enlisted in the military. By 1920 the principals had reconvened at Vanderbilt. Besides Ransom, Curry, and Hirsch, the original Fugitives included Donald Davidson, William Yandell Ellliott, Stanley Johnson, and Alec B. Stevenson. After the war a number of students and poets from outside the Fugitives’ circle also began to attend the meetings. Among their number were Merrill Moore, Allen Tate, Jesse Willis, and subsequently Alfred Starr, Robert Penn Warren, and, of course, Lytle himself.

By the autumn of 1921, when Lytle came to Vanderbilt, the Fugitives were meeting fortnightly at the home of James M. Frank, a Nashville businessman and Hirsch’s brother-in-law. These meetings followed no prescribed organization. Participants to turns reading one of the poems they had written, always providing copies for the audience. An intense and relentless critical discussion followed each presentation. No aspect of a poem escaped scrutiny. Exquisite or daring poems often inspired the greatest controversy, while mediocre or conventional poems evoked little comment. “In its cumulative effect,” Davidson remembered, “this severe discipline made us self-conscious craftsmen, abhorring looseness of expression, perfectly aware that a somewhat cold-blooded process of revision, after the first ardor of creation had subsided, would do no harm to art.”[6]

At Hirsch’s suggestion, the group agreed to publish a magazine of verse. Having already accumulated a substantial collection of work, they needed only to select the poems to comprise the first issue. They did so by secret ballot without designating anyone to assume editorial responsibilities. Davidson recorded the outcome of the first vote on the back of a letter from Vanderbilt chancellor James H. Kirkland informing him that no university apartments were available.