Shelby Foote: The South’s Jewish Proust

Blake Smith at The Tablet

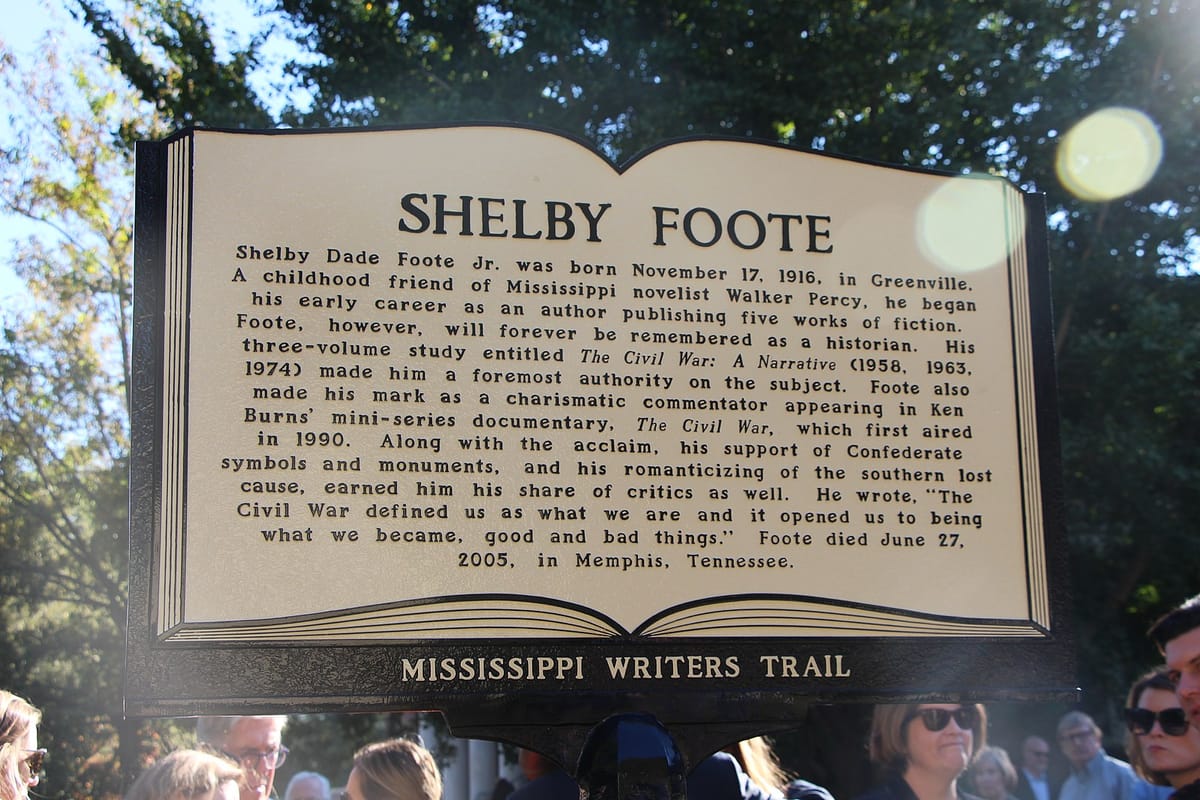

Shelby Foote (1916-2005) was one the greatest American writers—one of the greatest Jewish American writers. His trilogy The Civil War: A Narrative, published between 1958 and 1974, is to history what Proust’s In Search of Lost Time (Foote’s favorite and most-read book) is to the novel, masterful in its staggering scope, architectonic sentences, and dazzling reversals of perspective and characterization. Descended, on his father’s side, from Mississippi Delta planters, including a Confederate commander at the battle of Shiloh, Foote played in public the blue-blooded raconteur. His appearance in Ken Burns’ The Civil War documentary in 1990 made him, for millions of viewers, synonymous with a genteel unctuousness imagined as typical of elite Southern whites.

Of his mother’s family—Vienna Jews who came to the Delta town of Greenville late in the 19th century—he rarely spoke, although, his father having died when he was 5, it was they who had raised him. Greenville’s small, bustling Jewish community, documented in the writing of its other most notable son, David Cohn (Where I Was Born and Raised, God Shakes Creation, The Mississippi Delta and the World), its synagogue, which he attended until the age of 11, and the inner life of its members hardly appear in Foote’s writing; he cannot be called a “Jewish novelist” in the sense meant for his contemporaries like Saul Bellow, Philip Roth, and Bernard Malamud.

He lived his Jewishness not as membership in a faith or a community but as something uncomfortable, half-secret, to be concealed or escaped. This may have been just what enabled him to become our country’s greatest student of Proust, whose biographical similarities to himself Foote surely understood and never discussed with interviewers. Foote was never more than a second-rate novelist—whether Southern, Jewish, or anything else—but, after a two-year writer’s block put him at the precipice of suicide, he applied himself to history as one of the most masterful stylists in American letters, doing in nonfiction what he could not do in fiction, and letting himself in the process be mistaken for the archetype of the pure-bred Southerner.

Foote did indeed identify with the South, and defend it with less the objectivity of a nonprofessional historian than with a political passion understanding of it as a victim of the American empire whose most compelling exponent—Abraham Lincoln—he unreservedly admired. His vision of history and politics, as the turns of the preceding sentence suggest, was far removed from the categories invoked by those today who would cancel or rehabilitate him. It hinges on a notion of honor—as what the artist seeks to win for himself and what the descendant owes to his forbears—that must have been particularly acute in a man who played the proud scion of Southern gentry to hide the other half of himself.

In a 1970 interview, after he had become, thanks to his leading role in Ken Burns’ documentary, not only respected by fellow authors and read by Civil War buffs, but a nationally famous image of Dixie gentility, Foote discussed, as he often would in later interviews, his father’s planter family, and—as he would hardly ever do after in public—mentioned his mother’s, who had come “from Vienna … from the world outside.” He did not say they—or he—were Jews. He went on to describe Greenville, where he grew up, as a cosmopolitan little town, where Chinese, Middle Eastern, and European merchants and craftsmen lent an unusual degree of diversity to Delta life. He noted—as if it had not been a personal concern—that hostility to outsiders was common elsewhere in the region, and that antisemitism was rife in towns just down the road, where Jews were excluded from country clubs, passing over his own experiences of discrimination.

What he learned about being different—and how to disguise it—came to him perhaps from William Alexander Percy, eccentric landowner, semicloseted homosexual poet, and uncle of Foote’s closest friend, Walker Percy, who mentored the fatherless Foote during his adolescence. William Alexander Percy introduced him to the emerging canon of literary modernism, to writers like Thomas Mann (his own mother, however, gave a 17-year-old Foote In Search of Lost Time). Uncle Percy was one model for how a man with a galling sense of interior difference might nevertheless cultivate himself in public as a model planter and Southern conservative; his 1941 memoirs Lanterns on the Levee are what must strike present-day readers as a bizarre compound of apologia for white supremacy (provided it is exercised not by ungenteel populist rabble-rousers but by dignified planter aristocrats), veiled defenses of “Greek” love, and swooningly purple descriptions of Southern moonlight, magnolia, and other such set-pieces of stereotypical down-home Arcadia. Foote learned much from William Alexander Percy, but neither he nor Nephew Percy (later a Catholic existentialist novelist under the influence of Allen Tate and Caroline Gordon) would become such a reactionary.

After adolescence, two years at the University of North Carolina (during which he was barred from the fraternity his friend Percy had joined, when its members somehow learned that he was Jewish), military service blotched by his going AWOL (to fool around with a woman who would, briefly, be the first of his three wives), and a stint in local journalism, Foote became, and rather quickly, a novelist of some skill and reputation. He modeled himself on Faulkner—whose work William Alexander Percy failed to admire, because the author had once showed up at his house to play tennis, incapacitatingly drunk—who, in the 1930s and ’40s was himself becoming one of the most powerful writers in our national (and even more so in our Southern) literature.

Of his own early work Foote later said, “I had an excitement about language that flawed” the writing. The first draft of his first novel, Tournament, written in 1939, contained ramshackle mad sentences like: “Its dusty brick rainstreaked, its low pillars garbled, itself gutted, despoiled, vacant now for two years, with an air of febrile advocacy, a charivari of grandeur, possessing grain for grain the texture and stuff of the dregs of nothing more than backward yearning hope, recapitulant, somnolent, now tinted by the red rising sun behind it, the panache of dust and desire …” Such horrors were meant to imitate Faulkner, echoing, with turgid excess, the description of a similar house in Sanctuary (1931) “a gutted ruin rising gaunt and stark out of a grove.”

By the end of the decade Faulkner would become one of the eternal masters of American English, not least for his unheralded combinations of adjectives, but during Foote’s apprenticeship to literature he too was finding his way. Light in August (1932), for example, has its beauties, but they are proximate to disaster, as in: “The house, the study, is dark behind him, and he is waiting for that instant when all light has failed out of the sky and it would be night save for that faint light which daygrained leaf and grass blade reluctant suspire, making still a little light on earth though night itself has come.”

Here Faulkner—who had meant first to be a poet—channels Charles Swinburne and Gerard Manley Hopkins (like his American contemporary Hart Crane) to gush unmodern bathetic guff in an inverted Latinate style. Faulkner would do much better than this, soon—and at his best wrote what few will ever equal. He was still learning how to shift his bloated neologizing into a register capable of vatic pomposity, but definitively removed from the ridiculous to the cosmic, and also (perhaps from his experience writing scripts for Hollywood) capable of all the other registers of speech besides faux-antique grandiloquence.

Over the course of his apprenticeship in fiction, Foote gradually freed himself from sub-Faulknerian imitation, and moved into a maturer style characterized by graceful, sometimes mannered, even Olympian, detachment which, rather than being the mere embodiment or extension into discourse of the violence it conveyed, could now chillingly contrast it, as in this scene of the story “Child by Fever” from Jordan County (1954), which in its masterful cruelty puts its author on the level of Hardy in Tess of the d’Urbervilles:

By Tuesday the rector was onto crutches, and ten days later, on Christmas Eve, Hector Wingate, hard-faced now in his middle fifties—he had gotten so he rarely spoke to anyone, and whoever spoke to him risked offense, either given or received—was killed by a Negro tenant following a disagreement over the ’77 crop. Thus at last he achieved his heritage of violence; it had been a bloody death, if not a hero’s. The tenant was caught late that night, treed by dogs in a stretch of timber east of town, and lynched early Christmas morning. That was the one they burned in front of the courthouse.

The deaths befall in passive voice, as if of no importance, and the lynching of any particular Black man appears so difficult to remember amid all the others (revealing, with such faint indirection, generations of organized murder) it must be distinguished with a “that was the one” addressed to the reader who, thus presumed to remember, is made one of the community of whites who have long been dispensing such violence. Playing long sentences in which dash-suspended digressions hang like narrow bridges against short, blunt ones, and lofty sententiousness (“Thus at last he achieved his heritage of violence”) against brutal directness (“That was the one they burned”), Foote showed himself a skilled writer—except that his attempts to give voice to a range of social classes and character types were more or less failures, all speaking alike the emergingly confident and distinct timbre of the Footean narrator.

He was, without knowing it, preparing himself to become a writer of history—a genre in which he would be spared having to invent distinct voices for his characters, who rather speak for themselves through the primary sources. Even as he learned to control his sentences, Foote deftly played with shifts in perspective among multiple narrators, culminating in his novel Shiloh (1952). In that final novel before he began the Civil War trilogy, battle passages are long, expansive, but tightly organized, tracking from one side to another, Union to Confederate, back and again, up and down through all levels of experience, from the general’s expansive vision to the private’s narrow baffled terror.

It spins around so many different perspectives that the reader may wearily grant Foote the prize in kaleidoscopic capacity, while regretting the neglect of human feeling (it is in that sense no surprise that Foote’s novels were appreciated less in America than in France—where Faulkner’s success in translation had paved their way, and where readers of the New Novel and its anti-narrative techniques and learned to savor fiction organized as a kind of ballet, a kinetic exercise, rather than an exploration of affect and personality in action). Foote’s notes and drafts for his novels and stories from the late ’40s and early ’50s are filled with charts of how interlocking shifts in perspective will outdo the accomplishments of Faulkner and other modern novelists who pioneered them in the decades prior, hardly sketching however a character or considering plot in terms of its psychological motivations rather than such intricate, sterile mechanics.

By the beginning of the 1950s, with the completion of Shiloh, Foote had written four novels and a collection of short stories, all of which did moderately well in sales and reviews. In late 1951 he felt ready to tackle what he planned in his diary to be a tremendous, multigenerational novel about a Delta family (gentiles) to eclipse Faulkner’s own sagas. In a letter to Walker Percy on Dec. 31, he crowed, “I’m among the greatest American writers of all time … and at the age of thirty-five.” The next New Year, after 12 months of uninterrupted writer’s block, he confided to his diary, “Bad situation—the kind that leads to suicide with some people.” His novel—Two Gates to the City—was going nowhere; another marriage had failed; he was broke.

When a publisher, appreciating the historian’s art on display in Shiloh, offered Foote a contract for what was supposed to be a short nonfiction overview of the Civil War, he had little choice but to accept, although it soon became not a quick cash-grab but his 3,000-page, two-decades-long masterpiece, the real work of his life.

Faulkner had been in Foote’s way; Proust was the light to his path. He had read In Search of Lost Time several times through before beginning the Civil War trilogy, and it was from Proust he learned the abilities essential to such a long, digressive narrative—which turns apparently meandering and spontaneous but moves only with its author’s deliberate, far-seeing and much-remembering care—to its long, digressive sentences, and to the art of characterization by which Foote, following Proust, would supply a telling detail at just the right moment to surprisingly revise the reader’s understanding. Here he added something new to his acquired mastery in moving among different perspectives, and became, albeit with found rather than invented characters, a master novelist, one who lets personalities shine out in action and be mirrored in the reactions of others. Foote does this even for the smallest characters who appear only briefly to receive a command or charge across a field.

Volume 3 of the trilogy, for example, begins with Grant, haggard, thin, fairly ugly, unphotographed and thus unfamiliar, visually, to the public, upon his arrival in Washington to receive command of the eastern theater:

Late afternoon of a raw, gusty day in early spring—March 8, a Tuesday, 1864—the desk clerk at Willard’s Hotel, two blocks down Pennsylvania Avenue from the White House, glanced up to find an officer accompanied by a boy of thirteen facing him across the polished oak of the registration counter and inquiring whether he could get a room … Discerning so much of this as he considered worth his time, together perhaps with the bystander’s added observation that the applicant had ‘rather the look of a man who did, or once did, take a little too much to drink, the clerk was no more awed by the stranger’s rank than he was attracted by his aspect. This was, after all, the best known hostelry in Washington. There had been by now close to five hundred Union generals, and of these the great majority … had checked in and out of Willard’s … The desk clerk … still maintaining the accustomed, condescending air he was about to lose in shock when he read what the weathered applicant had written: ‘U.S. Grant & Son—Galena, Illinois’

This extract condenses the opening paragraph, which occupies more than a full page, wherein Grant’s taking command, with all its consequences, is introduced first through the snobbery of character so minor as to be otherwise invisible to history. This is Proust at war.