Place and Conservatism

Mark T. Mitchell at Front Porch Republic

In one sense, there is nothing wrong with conservatism. The principles remain; reality has not changed. The problem lies in the fact that what passes for conservatism today is not conservative at all or at best a shadowy and distorted version of the real thing. The so-called conservatism promoted by Fox News and Rush Limbaugh is (when a coherent thread presents itself) a fairly standard litany of pro-growth, pro-war individualism, that claims to despise “Big Government” while championing the upward mobility of the most talented and energetic. These ideas, and the policies they spawn, are not conservative.

Our cultural standard-bearers chafe against the notion of limits. We are told that freedom and limits are incompatible, and that freedom is only real if limits are ignored. We are told by advertisers that our limitless appetites are normal and their satisfaction is an indicator of our success. Appetites, however, are boundless and some might recall that the virtue of self-control has, in earlier times, been deemed an important feature of a well-formed character. Self-control and limitlessness do not readily mix.

We are told that the solution to our economic woes is growth. We need steady and sustained growth in order to ensure that our standard of living continues to improve indefinitely. No one seems interested in asking whether infinite growth is even possible. No one seems inclined to ask whether our standard of living is sufficient or even sustainable.

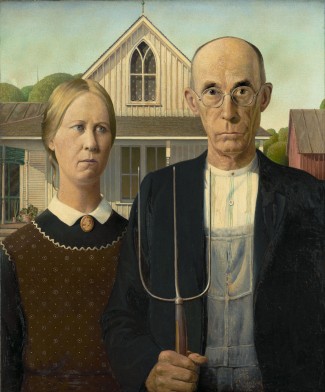

Americans have always been a restless people. We believe that to be in motion is the key to productivity, and productivity is an indicator of worth. The idea of upward mobility is especially attractive to those who find themselves twice blessed with both talent and opportunity. To improve one’s position, to continue to steadily mount the ladder of success, one must relocate or at least be ready to do so. Any commitment to a particular place or a particular community must come in a distant second behind the ambition to succeed. The notion that a person might forgo opportunities in order to stay rooted, in order to stay home, smacks of parochialism, shiftlessness, and misplaced priorities.

Mobility is encouraged by (and in turn helps cultivate) a conception of the human person as primarily an individual and only accidentally a member of a community, a parish, or even a family. On the surface, this conception of the person would seem to carve out the maximal space for individual freedom, for if all of my relationships are purely elective and transient, then I am much freer than if at least some of my relationships are natural, durable, and bring with them obligations.

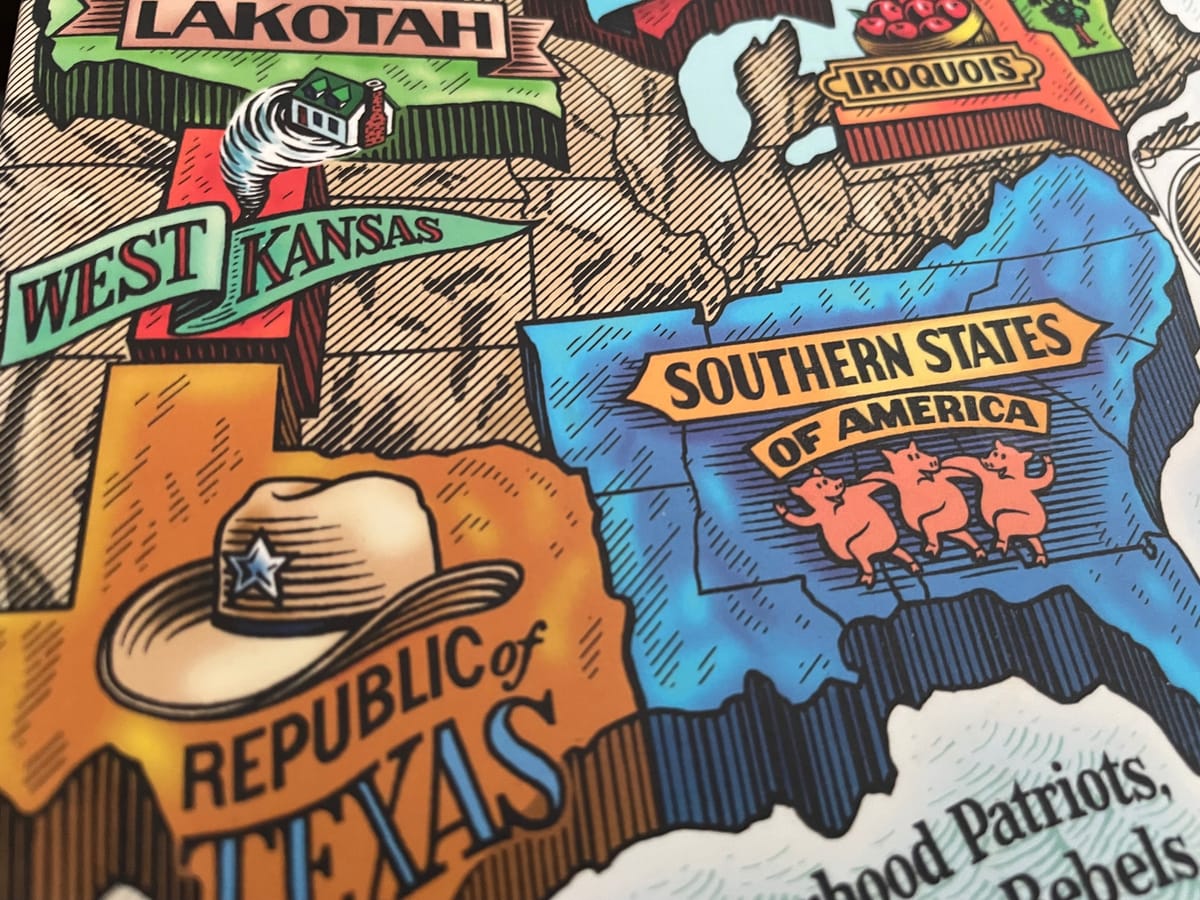

Ironically, this conception of the autonomous individual helps to facilitate the growth of the centralized state. Robert Nisbet, in his classic work The Quest for Community, argues that as intermediate institutions eroded under pressure from both the state and changing social patterns, the natural longing for community remained as a constant feature of the human constitution. While virtually all means of satisfying that longing were breaking up, the monolithic state emerged as the one enduring institution. People naturally began looking to the state to fulfill their desire for community and as a result the state enjoyed a burst of energy that only aided in the centralization of its power. In short, the atomized individual, far from being a means to maximizing freedom, was and is instrumental in the growth and empowerment of the centralized state.

So, too, the idol of perpetual economic growth. Where the role of the government in the economy is generally accepted as necessary and good and where the lines between Washington and Wall Street are increasingly blurred, the inevitable outcome is the concentration of both economic and political power. Is anyone still naïve or blind enough to deny the incestuous relationship between Big Business and Big Government? In fact, both helped to create the other and both need each other to exist. Many “conservatives” rail against Big Government, but this is only part of a complex problem. Through regulatory capture, tax “incentives”, and the specter of too big to fail, Big Business continues to exercise power far beyond what is legitimate or safe. To ignore this is to ignore a crucial aspect of the problem of concentration and, incidentally, to prevent an effective reduction in the scope and power of Big Government.

Read the rest