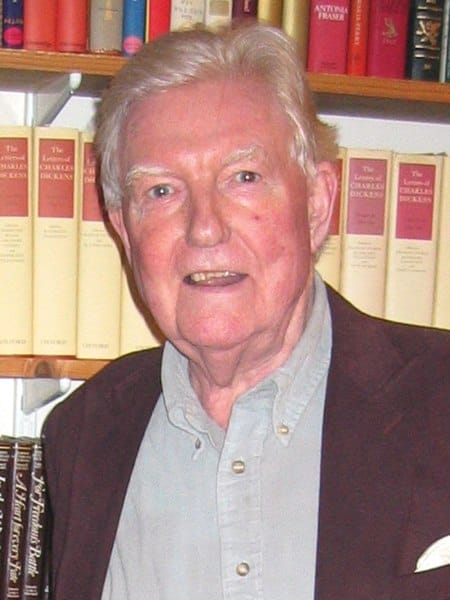

Paul Johnson, 1928–2023

By Adrian Goldsworthy at The New Criterion

Roger Kimball writes: What follows is a brief personal reflection about my friend Paul Johnson, the English journalist and historian who died last month at ninety-four. I do not recall when we first met, or even whether it was on this or that side of the Atlantic. Probably, it was in the late 1980s. I do know, however, when I had my last glimpse of him. It was just a few weeks ago, near Christmas, when we received, as we have for a couple of decades, a card filled out by Marigold, Paul’s wife of more than sixty years. Marigold’s cards were usually upbeat. The first I recall was accompanied by a little red hat in the form of a strawberry for our then-infant son. That was more than twenty years past. This year, the card was accompanied by a photograph of Marigold and Paul, she smiling, sitting next to Paul who was lying propped up in bed, a sort of half-smile playing about his lips and a wandering glance emanating from his half-open eyes.

Alas, Paul had been ill for several years. Time was, no trip to London was complete without a stop at the Johnsons’ house on Newton Road (how perfect that this great man lived on a road named for England’s greatest mathematician). Marigold, an excellent cook, introduced me to salmon coulibiac, now one of my favorite dishes, and, on that same occasion, perhaps the best summer pudding I have ever tasted.

Those were marvelous visits, sometimes for lunch, sometimes dinner, sometimes Mass followed by lunch. At one, I met the great Australian historian Geoffrey Blainey (The Tyranny of Distance) and his wife Ann, the biographer of the nineteenth-century actress, writer, and abolitionist Fanny Kemble and her opera-singer sister Adelaide. Both Blaineys became friends. It was always a special treat when Paul took me out to his painting studio in the backyard. His father was an artist and the head of an art school. Paul, an accomplished watercolorist himself, had contemplated a career as a painter. His father, though he acknowledged Paul’s skill as a draftsman, put him off art as a career. “I can see bad times coming for art,” he told his son: “Frauds like Picasso will rule the roost for the next half-century. Do something else for a living.” Paul took the advice to heart in two senses. In his professional life, he exchanged paintbrush for pen (or typewriter), and he nurtured his father’s animus against Picasso. Many readers will recall that there was a period when Evelyn Waugh ended his letters with the cheery valedictory, “Death to Picasso!” Paul came from a kindred school, as the title of his 1996 collection To Hell with Picasso and Other Essays reminds us. In his book on the history of art, Picasso emerges as an archetype of what he called “fashion art, as opposed to fine art”—that is, art as a species of hucksterism.

Paul’s view of Picasso (who died, he tells us, “the richest artist in history”) is one of the things that furrowed the brows of his critics. But it is worth noting that while he was hostile to Picasso, he was not cavalier. Picasso, he acknowledged, raised unique problems in the history of art, so “it is important that everyone should make up [his] own mind about him.”

Paul’s rejection of Picasso had less to do with Picasso’s deplorable character—he was, quite simply, a swine—than with Picasso’s attitude towards his own art. Paul was quite tolerant about the foibles of artists, Picasso’s and others. What he objected to was not so much Picasso’s exploitation of people as his exploitation of his talent to gratify the demands of his ego (and that reliable appendage of ego, the

pocketbook). If Paul was right, Picasso helped to license the attitude that Marshall McLuhan summed up when he said that “art is anything you can get away with”—the attitude that prevails in many of the most respected quarters of the art world today. In any event, I was pleased indeed that over the years Paul gave me several of his watercolors. At least two occupy honored spots on the walls chez Kimball.

My diary tells me that my last visit with the Johnsons was in 2014 for tea. By then, Paul’s acuity was already somewhat dimmed. He knew who I was and even, when I got up to leave, insisted on accompanying me outside to find a cab. But the ferocious, rubicund intellect that had always issued from him was clearly beginning to falter.

How different things had been. For decade after decade, Paul had been a prodigy of articulate, often polemical industry. His writing was sinewy and seductive. Paul was the master of the engaging anecdote, the memorable tidbit. You know what “shrapnel” is. But did you know it was named for Henry Shrapnel, the British lieutenant general who, in the 1780s, invented the hollow-case shot of the shell that today bears his name? And speaking of detonations, Paul also regularly dispensed little morsels of common sense that were sure to raise the hackles of the politically correct. “One reason why garages tend to cheat customers today over repairs,” he explained, “is that they had their origin in horse-mongering, thus preserving an unbroken tradition of fraud.” We may not have known the connection to horse trading, but we all recognize the truth of the observation, even if we are not supposed to admit it.

Paul’s literary output was breathtaking. He wrote regular columns for—well, for everyone, it seemed. Over the years, he wrote several pieces for The New Criterion. The first, a tart review of Barbara Tuchman’s March of Folly, appeared nearly forty years ago, in 1984. His last, an essay called “The human race: success or failure?,” appeared in our twenty-fifth-anniversary season of 2006.

Read the rest (subscription might be required, but I don't think so)