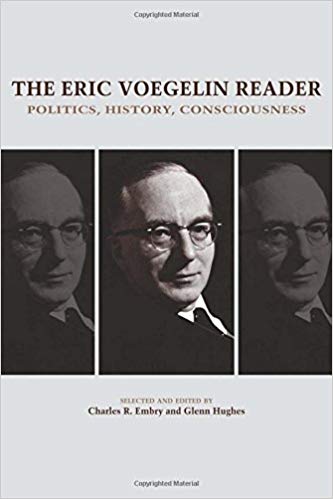

Voegelin’s New Science of Politics Put Gnosticism Back into Our Awareness

Time magazine ran a peculiar feature in 1953.

It used a five-page analysis of The New Science of Politics to celebrate the magazine’s 30th anniversary, stating that Eric Voegelin had made a significant breakthrough in political theory by, among other things, showing that modern totalitarian ideologies are the equivalent of the ancient Christian heresy of gnosticism.

Ancient Gnosticism Rejected the World and Said It Had the Knowledge to Escape It

So, what is this “gnosticism” thing?

Well, for starters, let’s admit that it probably isn’t a great term. Voegelin later in life regretted using it. It’s too broad. It has manifested itself in different ways throughout history, resulting in a conflation of historical facts and intellectual concepts that don’t always mesh well.

But “gnosticism” in its most encyclopedic definition refers to an early Christian heresy that celebrated knowledge over faith. The gnostics claimed to have special knowledge (gnosis) from Jesus Christ (or other sources) that gave them privileged insight into the means of salvation.

This special knowledge was normally knowledge about how to escape earth. The ancient gnostics taught that this world is made by an evil god (the “demiurge”) and that it’s necessary to escape it. The means of escape: the special knowledge taught by the gnostic leaders.

That’s the primary two-part thing you need to understand about ancient gnosticism: It rejected earthly existence (either asserting that it’s evil or that it’s all an illusion meant to trap us) and claimed to have the knowledge to escape it.

Alexander the Great Disrupted Meaning

It’s hard to say when gnosticism first appeared, but it possibly appeared as early as the rise of the first ecumenical empires, such as the Persians (the ones that the Greeks beat at Marathon in 490 BC).[1]

Ecumenical empires messed things up. They displaced populations (e.g., the Babylonian Exile that started in 589 BC); they resulted in mass migrations; they forced insular communities to co-exist with weird people.

The messiness went steroidal with the empire established by Alexander the Great, which was divided after his death among four of his generals. These empires in turn fell to new massive empires, like the Roman Empire.

These huge movements disrupted local life. City-states collapsed. No longer was your world just your city and agricultural land surrounding it. Your world was now, well, the whole world. The world came to your doorstep . . . or you were taken to its doorstep. Huge enslavements. Huge population shifts. Cultures collided, either through migrations or trade.

There was a loss of cohesion: emotional, cognitive, intellectual.

There was a general loss of meaning: local institutions, regional civilizations, and ethnic identities snapped apart.

Christianity First Appeared in this Age of Havoc

People can’t live without meaning. So there were at this time new attempts to structure meaning out of the new reality. Stoicism was one of the biggest responses to this crisis of meaning. So were mystery cults and various apocalyptic movements within Judaism and Manichaeism.

Into this milieu stepped Christianity.

And so did a ramped-up gnosticism, fueled by that strange persona, Jesus Christ, and his fervid early disciples.

Gnosticism was immediately at war with Christianity, appearing in the Book of Acts in the person of Simon Magus.

Christianity is Uncertain and Many People Can’t Take It

Christianity is a hard religion. Not only is it paradoxical to the core (the God-man, the mortal Immortal, one must lay down his life to save it, the virgin birth, etc.), but it is also highly “differentiated,” meaning that it separates earth and heaven, making the spheres separate, though also connected in some fashion (traditionally, through the sacraments . . . hence the “sacramental view of creation” that underlies all Catholic thought).

The full drama (and problem) that Christianity presented to the world was vibrantly painted by Voegelin in The New Science of Politics:

Uncertainty is the very essence of Christianity. The feeling of security in a ‘world full of gods’ is lost with the gods themselves; when the world is de-divinized, communication with the world-transcendent God is reduced to the tenuous bond of faith, in the sense of Hebrews 11:1, as the substance of things hoped for and the proof of things unseen. . . . The bond is tenuous, indeed, and it may snap easily . . . The more people are drawn or pressured into the Christian orbit, the greater will be the number among them who do not have the spiritual stamina for the heroic adventure of the soul that is Christianity; and the likeliness of a fall from faith will increase when civilizational progress of education, literacy, and intellectual debate will bring the full seriousness of Christianity to the understanding of ever more individuals.[2]

Christianity is “uncertain.” It takes “spiritual stamina.”

A lot of people, to be blunt, simply can’t take it. To be a serious Christian, you need to be a saint, a scholar, or a simple peasant woman in the pews with a rosary. You need to be (i) infused with love of Christ (saint); or (ii) intelligent and willing to undertake the serious study necessary to plumb the history, philosophy, and theology of Christian thought (scholar); or (iii) content merely to rely on faith and authority (peasant woman). Or perhaps an incomplete mish-mash of all three.

If a Person Can’t Accept the Uncertainty That is Christianity, He’ll Look for Certainty Elsewhere, Like the Certainty Offered by the Gnostic Worldview

If a person doesn’t have the spiritual stamina and can’t accept the uncertainty—the mysticism, the paradox—that lies at the core of Christianity, he or she will seek certainty, even if it means he or she must substitute a flawed reality for the real one.

That’s what ancient gnosticism did.

It said earthly reality doesn’t exist, either because it’s merely an illusion or because it’s an evil prison that keeps us from reaching the heavens. Instead of a vision of existence that includes the legitimacy of the world, it said full existence is strictly transcendent.

In other words, because it refused to accept the earth’s limitations, it devised a new “reality” that eliminated the earth. In order to enter that new reality, gnosticism told its followers that they needed special knowledge and had to absorb that knowledge.

Gnosticism Requires a Person to Buy Into a Flawed Version of Reality

In order to be an ancient gnostic, a person had to remake his intellectual core—his cognitive universe—and accept the fundamentally-flawed view of reality—of existence—taught by the gnostic master. This gave the ancient gnostic the “cognitive mastery of reality”[3] that he craved; indeed, demanded and devised and developed himself. He then taught it to others. If others believed it too, then it attained heightened legitimacy.

It didn’t matter if the ancient gnostic master’s fundamental premise (that the earth doesn’t exist or is evil) contradicted common sense and basic human experience. If a person wanted to get rid of the uncertainty ushered in by the great upheavals of the ecumenic empires and he couldn’t accept the sacramental and mystic uncertainty found in the new Christianity, gnosticism was a key to salvation.

The Gnostic Stands Beyond Rational Discourse

And if others disputed this odd version of reality? The gnostic didn’t care. To the gnostic, anyone who disagreed with his weird version of reality was simply ignorant and hopelessly beyond rational discourse. Such people, said the gnostic, were trapped in a world devised by the evil demiurge and lived in an illusion.

The only people the gnostic could speak with were people who accepted his weird version of reality. Everyone else? They were simply the ignorant, the sleepwalkers, the sheep. The gnostic couldn’t talk to them.

And none of them could talk to the gnostic.

The gnostic stood beyond criticism.

[1] Johannes Quasten, Patrology (Westminster, 1992), v. I, p. 254.

[2]Eric Voegelin, The New Science of Politics (University of Chicago Press, 1987), p. 123.

[3] Eugene Webb, Eric Voegelin: Philosopher of History (University of Washington, 1981), p. 282