Orestes Brownson: Pioneer Catholic

Part V of a Five-Part Series

If a person looks at maps of the world by early cartographers, he is struck by two inconsistent things: Their grotesquely disproportionate geographical features and their accurate geographical features. Looking at the maps with the benefit of another five hundred years of exploration and enhanced tools for observation (like airplanes), the maps are poor. But looking at the maps from the early cartographers’ vantage point, their accuracy is impressive.

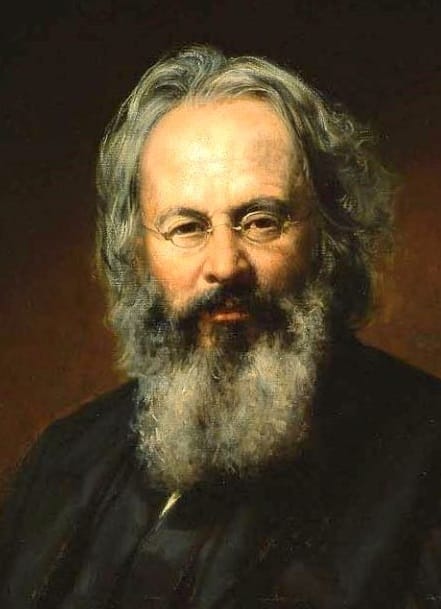

Brownson is the intellectual Gerardus Mercator of nineteenth-century America. He was the first of a species: The American Catholic. There were earlier American Catholics, but they were more American than Catholic, more Catholic than American, or gave little thought to either. Brownson was fully both: American and Catholic. Moreover, he was one of America’s earliest political philosophers and was the first American scholar to apply the question of the origin and ground of government to the American experiment.[i]

He was breaking new ground in difficult territories. Here is how John Courtney Murray explained the intellectual difficulties confronting the American Catholic almost one hundred years after Brownson’s death:

The Catholic may not, as others do, merge his religious and his patriotic faith, or submerge one in the other. The simplist solution is not for him. He must reckon with his own tradition of thought, which is wider and deeper than any that America has elaborated. He must also reckon with his own history, which is longer than the brief centuries that America has lived. At the same time, he must recognize that a new problem has been put to the universal Church by the American doctrine and project in the matter of pluralism, as stated in the First Amendment.[ii]

Brownson grappled on those mats back when American Catholicism was at its infancy. In light of this, his efforts were impressively accurate. He made mistakes, and his approach often wasn’t edifying or effectual, but no one should scoff at him any more than he would scoff at Mercator.

If at times one wishes he were a little less bold in his theorizing and expression, it should be remembered that a less bold person would not have converted in the first place, would not have held his conversion up for everyone to see, and would not have even attempted the speculations he put to paper.

Whatever his shortfalls, he recompenses with one overarching virtue: courage.

Like his contemporaries, the pioneers who blazed the trail westward, he blazed a trail for the Catholic Church in America.

[i] Ryan, p. 241.

[ii] John Courtney Murray, We Hold These Truths: Catholic Reflections on the American Proposition, Kansas City: Sheed and Ward, 1988, p. xi.