One Hundred Years of Platitudes

Giles Fraser at UnHerd

The Prophet is as spiritual as a Coca-Cola advert

The worst sort of books make you feel clever without actually making you more so. They flatter your intelligence, encouraging you to nod along in smug agreement at some faux deep observation, giving you a sense of achievement without having to do the sort of work that achievement rightly demands. Right up there with the very worst of them is Khalil Gibran’s The Prophet.

First published in 1923, and now a century old without ever having been out of print, The Prophet is one of the best-selling books of all time. God knows why, I want to say. But, unfortunately, I think I do know why. There is nothing people want more than the illusion of sharing in the readily profound. Especially when it is little more than a dressed-up version of what they already know. Beloved by wedding planners and popular at secular funerals, it is the lift music of the Abrahamic traditions. Gibran’s The Prophet is a shallow person’s idea of what deep looks like.

Its aphoristic style is the perfect vehicle for this sort of flattery. You don’t have to read the whole book or concentrate on some kind of extended argument. The promised wisdom is instantaneous: “Love one another, but make not a bond of love. Let it be rather a moving sea between the shores of your souls.” I can feel the ick rising in my stomach.

Gibran has an ear for what profundity is supposed to sound like. He is often doing that thing where opposites are knowingly affirmed: I am a man but yet not a man, they are your children but not your children. Hegel, this isn’t. There is no underlying philosophy.

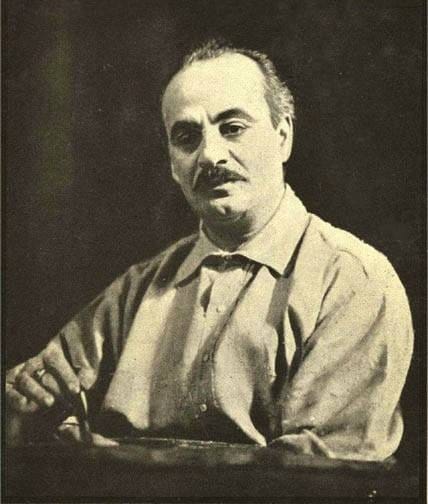

Born in Lebanon to Maronite Christian parents, Gibran emigrated to the United States with his family at the age of 12. Coming from a place where sectarian religious division was a fact of daily life, he quite understandably developed a life-long hatred for doctrinal religion as opposed to spirituality. For Gibran, as for many in the West today, religion divides, but spirituality unites. His preference for oceanic metaphors of universal immersion into the infinite — the sea, the sky, etc — reach for a sense of the numinous that does not rely upon the kind of theological divisions that have set the Middle East at violent odds with each other.

“I love you, my brother, whoever you are – whether you worship in a church, kneel in a temple, or pray in your mosque. You are I are children of one faith, for the diverse paths of religion are fingers of the loving hand of the one supreme being, a hand extended to all, offering completeness of spirit to all, eager to receive all.”