On Milosz, Exile, and Humane Art

Rachel E. Hicks at Front Porch Republic

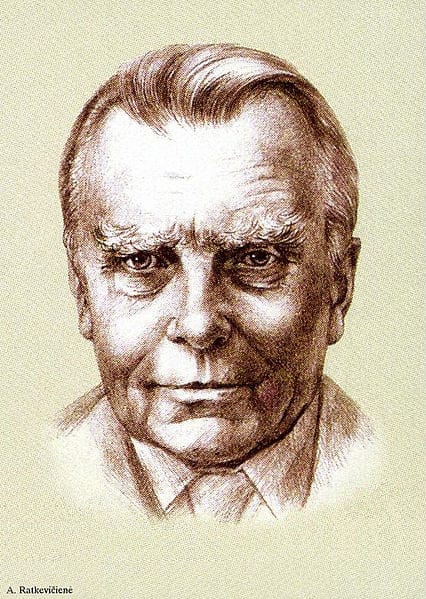

In my early thirties, I discovered the poetry and prose of Polish writer Czeslaw Milosz. I don’t remember the title of the first poem I read of his, but it was posted on a bulletin board in the hallway of the local community college. I began reading his poetry and prose, as well as Andrzej Franaszek’s Milosz: A Biography. I found in Milosz a kindred exiled soul. He has since become a sort of patron saint—albeit a strange one—to me.

I spent the bookends of my childhood in India—born in the foothills of the Himalayas, I later spent my last two years of high school in New Delhi. In between were stays in Pakistan, Jordan, the Democratic Republic of Congo, the U.S., and Hong Kong. Those who don’t get it ask me, “Where are you from?” Those who do get it ask, “Where is home for you?”

Any answer I give leaves me feeling fake and homeless—exiled. I could never claim to be “from” even the place that felt most like home, India.

Exile exacts a toll on the mind, body, and spirit. To carry always the weight of not belonging, of not being “native,” of not being able to return home, or not to be able to call anywhere on this earth home—it is a low burn, an irritant.

You learn to adapt by observing, by making a million small decisions about when to try to blend in and when to risk standing out. You chameleon yourself to each situation, each mini culture in which you find yourself. Sometimes you lose—your own self, the chance to embrace your difference, the opportunity to see from a new perspective.

Milosz lived most of his life—which spanned most of the twentieth century—in some form of exile, in mind as well as in body. That thread of exile runs through all his works. As his fellow intellectuals in Poland were choosing ideological sides—and although he leaned left—Milosz found himself uncomfortably alone in discerning where both Communism and Polish Nationalism were leading. One article by Adam Kirsch details that

By the end of the thirties, Milosz’s intellectual position was becoming intolerable. He was opposed to everything the Communists opposed, yet he suspected that a Communist takeover would be disastrous. At the same time, anyone could see that Poland’s future held war or revolution, or both. Contemplating the fate of his country, he wrote, years later, “I had a kind of horror, some basic dread.”

After a strong infatuation with Communist ideas as a young adult, he realized what the ideology meant for art, literature, truth, and humanity: “Nazism threatened the body, whereas Communism demanded the surrender of the soul. For a poet like Milosz, the latter seemed like the greater sacrifice.”

Despite numerous brushes with death, Milosz survived the Nazi occupation of Warsaw and the subsequent Stalinist-puppet Polish regime. Serving in the U.S. as a cultural attaché for the post-war Polish government, he came under increasing scrutiny back home for his “unorthodox” views. After being recalled to Poland and having his passport confiscated, he was fortunate when someone intervened on his behalf, convincing the government he should be allowed to represent Poland in Paris. Within days of his arrival in Paris in January 1951, he defected, requesting asylum.

Milosz knew the power of ideas and could intuit where they would lead. He wrote, “artists’ antennae pick up every wave; and they suffered, surprised that they did so.” He suffered from his premonitions, from his lived reality of war, siege, political danger, and exile—and from his memories and survivor’s guilt.

I know very little of those realities. Why, then, this connection I feel with Milosz? Is it intemperate pride to suggest that my antennae, too, sense what is coming and tremble—here, at the sputtering end of the Enlightenment project?