On “Edward Hopper’s New York” at the Whitney Museum of American Art

By James Panero at The New Criterion

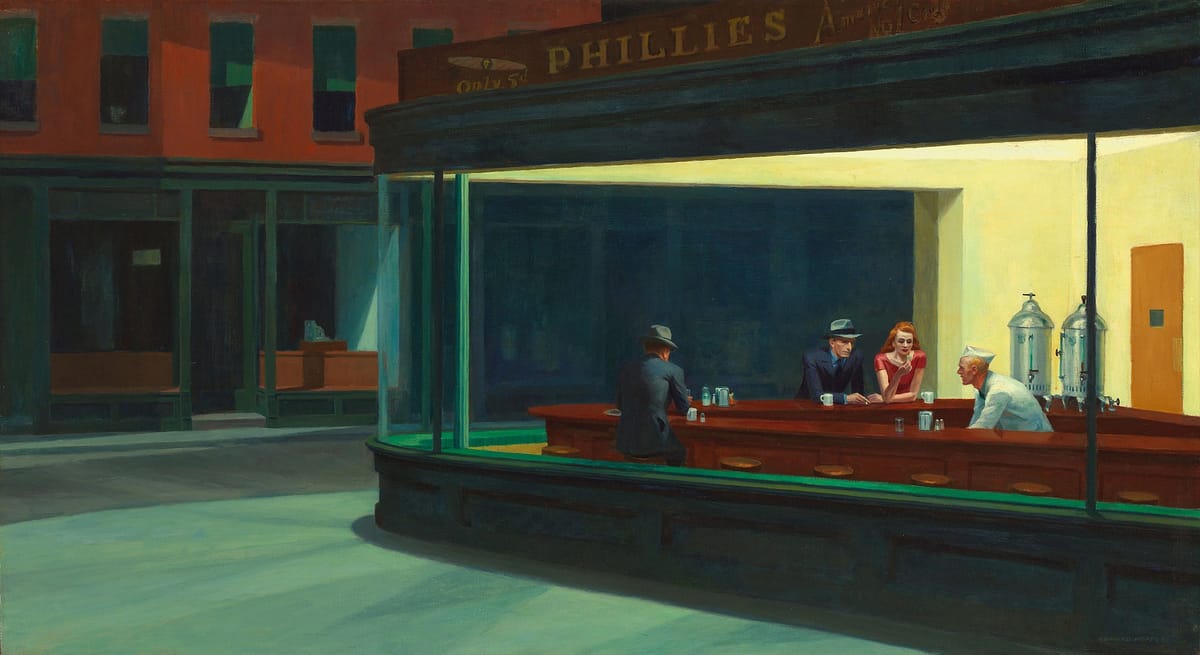

Edward Hopper (1882–1967) was the painter of small-town America. This we know. That his small town happened to be New York City, his home for nearly sixty years, we may not know. “Edward Hopper’s New York,” now on view at the Whitney Museum of American Art, tells the hometown story of an artist we thought we knew all along in a novel and illuminating way.1

It is certainly an achievement when an exhibition of a famous artist is able to surprise. When such an exhibition can also instruct and delight—and do so without resorting to the clichés of contemporary theory—this is a rare triumph. And when the subject is a dead white male painter—a conservative, anti–New Deal Republican, no less, who rejected every school and trend to look to the loneliness of the human condition—here is a show that must be seen to be believed. “Edward Hopper’s New York” is such an exhibition and will open many eyes to this artist’s elegiac vision.

Hopper treated New York as his own small town. Born just up the Hudson River in Nyack, he arrived in the big city as an art student at the turn of the twentieth century at a moment of dynamic change—and he wanted nothing to do with it. As the world looked ahead and up, he looked back and down to the remnants of what was left behind: the out-of-date storefronts and obsolete buildings and lost souls left to wander the urban stage. “Edward likes the surface of the earth,” observed his wife, Josephine (Jo) Nivison; “he likes to stay close to it.”

Then, well into the second half of the twentieth century, despite his burgeoning national renown, Hopper lived like a nineteenth-century recluse on the top-floor walkup of the same cold-water row house at 3 Washington Square North where he had settled in 1913. “We’re not spectacular and we’re very private,” Jo said at the height of her husband’s fame, “and we don’t drink and we hardly ever smoke.” To which Edward added: “I get most of my pleasure out of the city itself.” Hopper could be taciturn, difficult, a creature of habit. “Sometimes talking with Eddie is just like dropping a stone in a well,” said Jo, “except that it doesn’t thump when it hits bottom.” Yet when times demanded, he and Jo pushed back, refusing to move or modernize when Robert Moses, New York University, and the urban planners came calling—“progress” be damned.

Read the rest (subscription may be required, but probably not)