Mystical Sex, Theft, and Violence

One of the most perplexing groups in medieval history got strong in the 1300s.

“Whatever the eye sees and covets, let the hand grasp it.”

No, that isn’t a passage above the front door of Jeffrey Epstein’s residence on Little Saint James.

It’s a popular saying of a medieval sect known as the “Brethren of the Free Spirit,” which has long been regarded, according to historian Norman Cohn, as “one of the most perplexing and mysterious phenomena in medieval history.”

So perplexing, in fact, that Cohn himself conflated a genuine mystic, Henry Suso (1300-1366), with the Brethren. Suso, a disciple of Meister Eckhart, was one of the most Zen-like mystics in Christian history. Zen has Gnostic tendencies, but Suso was a legitimate mystic, as evidenced by his beatification in 1831.[1]

Suso lived in Cologne, Germany, which was the stronghold of the Brethren, but he was hardly like the Brethren of the Free Spirit.

Consider Suso's direct contemporary and fellow Colognian, John of Brunn, who lived at the Brethren’s House of Voluntary Poverty.

According to Brunn, since God is free, everything should be free: held in common. If anyone had more than he needed, it was merely so he could give them to the Brethren. If an adept ate at a tavern, he shouldn’t have to pay and, if the tavern keeper insisted on payment, he should be beaten. Cheating, theft, and violent robbery were all justified for Brethren adepts, according to John Brunn, who also testified in 1340 to lying, fornicating, orgies, incest, sodomy, and murder (including infanticide).[2]

Western Europe: Survival Mode to Luxury Mode in 200 Years

Starting around 180 AD, western Europe started a long decline. It was with the death of Emperor Marcus Aurelius and ascent of his corrupt son, Commodus (of Gladiator fame). Gibbon, for good reason, starts his magisterial Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire (after a few preamble-ish chapters) with the reign of Commodus.

The decline accelerated greatly in the 600s as the Muslim conquests cut off trade on the Mediterranean. Europe then crashed into survival mode in the 800s as trade was eliminated, society was reduced to subsistence farming and barter, Vikings invaded from the north, Muslims pushed from the south, and Magyars (Hungarians) swarmed from the east.

But things started to stabilize in the 900s. In 912, the great Viking Rollo took over Normandy, converted to Catholicism, and swore to defend against further Viking invasion. In 933, Henry the Fowler routed the Magyars and then his son, Otto the Great, thrashed them again in 955, marking an end of major Magyar aggression and resulting in their conversion in 1000.

Although Islam continued to be a threat, things were greatly improving in Europe.

Most significantly, Europe entered a long economic boom, starting around 950. Towns grew. Trading flourished. A merchant class arose. Coins returned (eliminating the need for cumbersome barter).

By the early 1100s, western Europe was enjoying unprecedented wealth. Luxury was on display everywhere.

A Tale of Two Poor Dudes

First Dude: In 1173, a wealthy merchant heard the legend of Alexis of Rome, a saint who left his family to live a life of celibacy. The story made a profound impact on the merchant. He decided his wealth was incompatible with the Gospels, so he provided for his wife, put his two daughters in a monastery, gave the rest of his money to the poor, then went out to preach. He was persuasive, eloquent, dynamic, and charismatic. He attracted a group of followers and they were soon preaching to wide audiences.

Second Dude: In 1206, the son of a wealthy merchant heard a voice telling him to repair God’s church. The son went to his father’s shop, grabbed a bunch of stuff, sold it, then took the money to repair a local church. His father beat him and locked him up. His mother later freed him. In 1208, he cut all ties to the world: his father, his inheritance, everything, then set off wandering and preaching. He soon attracted followers.

The first dude is Peter Waldo. Ecclesiastical authorities refused to give him license to preach. He became bitter and heterodox. He was excommunicated in 1182 and his followers, who splintered into a number of groups, and, to avoid repression by the authorities, went (almost literally) underground, living in deep Alpine valleys as Waldensians until they were absorbed into sixteenth-century Protestantism.

The second is St. Francis of Assisi. Innocent III endorsed his vow of poverty, his way of life, and his growing order of followers. The Franciscans flourished.

Wealth Means Poverty

When Europe was in survival mode, the Gospel injunction of poverty was pretty easy to follow. Even powerful lords in the 800s lived pretty shabbily: poorer than the average rural farmer in, say, Nebraska today; surrounded by more danger than the average denizen in, say, east Detroit today.

But when everyone is getting wealthier, that poverty thing starts to get harder. A person must buck against the system to embrace it. Hence, the rise of Peter Waldo and the Waldensians.

But folks who buck against the system tend to be problematical and often resistant to authority. Hence the ex-communication of Peter Waldo and repression of the Waldensians.

But Waldo didn’t change a fundamental fact: there was an increasing need in light of Europe’s increasing wealth to emphasize the importance of poverty: to channel it in a constructive way. Hence the endorsement of St. Francis of Assisi and support for the Franciscans.

It seemed like beggars with erections were everywhere

It seemed to work.

For awhile.

The Waldensians weren’t the only heretical group to embrace poverty and a sense of spiritual superiority. There were many such groups, including the notorious Cathars (Albigensians), which another new mendicant order, the Dominicans, would preach against.[3]

There were also Amaurians, folks who followed the teachings of Amaury of Bene, a lecturer at the University of Paris. These became known as the Brethren of the Free Spirit and their teachings were problematical, embracing “mystical antinomianism,” which basically means poverty infused with free love, along the lines (not coincidentally, for reasons I’ll explore in later columns) of the 1960s horizontal shenanigans in San Francisco’s Haight-Ashbury.

But the Church got them all under control through a carrot-and-stick approach. The Church issued bulls and anathemas, preached homilies, and urged secular rulers to stamp them out (the stick). The Church endorsed the Franciscans and Dominicans, giving members a healthy outlet for this new existential need (the carrot).

They largely went away.

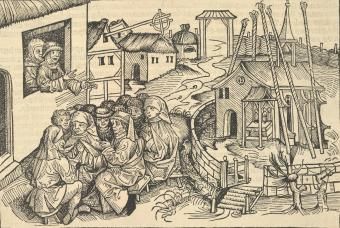

But only for about 50 years. They then re-emerged, vigorously, in the early 1300s. Brethren, Beghards, Beguines.

It seemed like beggars with erections were everywhere.

Existential Challenge Provokes Essential Change

What happened?

The 1300s happened. Things started falling apart for Europe economically

It has been a theme in these Monday columns (see here, here, and here): in the late 1200s, things started to fall apart. When the Papacy was moved to Avignon in 1309, thereby shaking the psychological link between the Eternal City and the divine, Europe psychologically shook. That’s what I think, anyway.

But we don’t need to limit it to a psychological thing, which obviously can’t be proven or disproven.

We can look to something verifiable, like finance.

And financially, things were shifting in Europe. For the first time in 350 years, the economy was contracting and not doing well. In fact, Europe had entered a great depression.

Murray Rothbard in Economic Thought before Adam Smith lays the depression at the feet of Philip the Fair (Philip IV) of France, who Dante properly called the “plague of France.”

Philip destroyed the fairs at Champagne, which were great trading sessions that brought together the North Sea economies with the Mediterranean. Philip crippled them with taxation. He then prohibited Flemish merchants from attending because he was fighting with the Flemings. Philip also destroyed the Order of the Templars so he could confiscate their wealth. He started war with England in the 1290s and instituted regular taxation to pay for it, including taxes on the Catholic Church. He debased the coinage (pulling back coins, melting them, then re-issuing them with less precious metal content and more base metal content).

The result? Trade was crippled and inflation ran high. The poor suffered the most, as they always do. They get paid in the debased coinage while prices are rising and their wages always lag behind. The Catholic Church, the primary source of poverty relief, was deprived of resources. The Knights Templars were gone, as well as the poverty relief they provided.

The new Brethren of the Free Spirit weren’t from the merchant class like Peter Waldo and St. Francis. Although the Brethren gained adherents from all classes, including the rich, it prevailed among the poor, especially the lowly weavers, who were the first to face the existential challenge that would be the fate of all of Europe during the 1300s.

Existential challenge, as I’ve pointed out previously, provokes essential change. The change takes different forms, and it seems like all of those forms were on display during the catastrophic 1300s.

[1] More (much, much more) on Gnosticism, as well as Zen, in later articles. For now, suffice it to say von Balthasar just flat-out stated that Zen is a type of Gnosticism. Anything tinged with it is tinged with a serious existential problem.

[2] See Norman Cohn, The Pursuit of the Millennium, 182-183 and Jeffrey Burton Russell, Dissent and Order in the Middle Ages, 78-79.

[3] The Dominicans preached against the Albigensians just like the Jesuits would preach against the Protestants 300 years later. Dominicans today like to joke about their superiority over the Jesuits, asking “When’s the last time you’ve seen an Albigensian?”