James Bond at 70

Titus Techera at Law & Liberty

Seventy years ago, in 1953, Ian Fleming, a British WWII planner and supervisor for commandos, published a brief espionage novel, Casino Royale, and thus James Bond was born. The book allowed Fleming to reimagine British imperial greatness and continue in fiction his command over manly men willing and able to kill and die for a cause, for the thrill of the fight, and for pride. He could speak for civilized society’s necessary assassins.

By the use of his imagination, Fleming became far more successful and important than he had ever been in public service. He ended up orchestrating one of Britain’s most successful cultural exports. Bond was in the mid-20th century what Harry Potter has been in the 21st century. But instead of a bespectacled nerd, ideal for the world wrought by selective colleges and Silicon Valley, audiences fell in love with a cold-blooded killer who seemed able and eager to refuse all the compromises the rest of us feel we have to make.

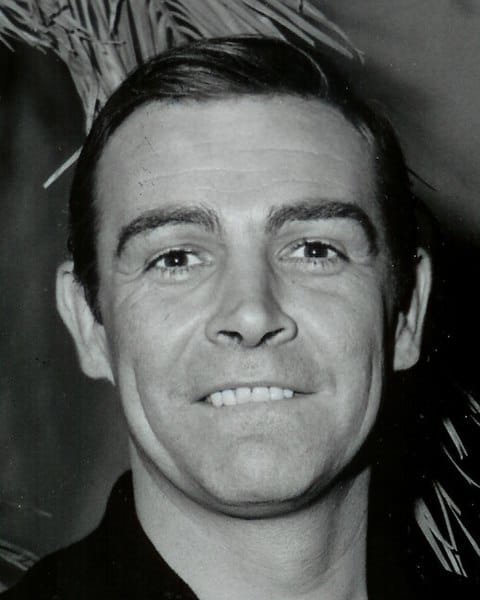

This image of manliness became more popular still, extending as far as mass-media could reach, nine years later, in 1962, when Dr. No appeared, starring Sean Connery as James Bond. All told, Fleming published twelve novels and two short-story collections, with another two novels published posthumously; these gave rise to 26 movies over the last 60 years; and these in turn led to countless imitations and new Bond stories penned by other writers, forever advertising the man of mystery, who combines love of beauty with a curiosity about the ugliest deeds imaginable.

Bond as Hero of the Empire

The novel-film combination also made for an unusual kind of stardom, leading four actors to fame: Connery, Roger Moore, Pierce Brosnan, and Daniel Craig, while maintaining the Bond glamour and spreading throughout the world, for generations, an ideal of manliness. I can’t think of anything that quite compares with it, because it’s still recognizable worldwide as British class presumption freed from its moral restraints or the silly eccentricities and melancholy bred by a stifling class system. Liberated, Bond is the sublime perfume of imperialism, the more popular the more people decry colonialism. As was once said of the British Empire, with its wars and diplomacy, so with Bond and espionage: The sun never sets on his adventures.

Bond, however, did not define martial prowess like the working class action heroes of the 80s and he was not a gym bro like the atomized middleclass men of our time. Connery had been a Mr. Universe bodybuilding contestant, but he’s worlds away from Arnold—his distinguished manners are supposed to conceal his power. Instead of brutality, he defined elegance for men, from the sharp suits to the frivolous witticisms, and especially his success with women.

After all, the great ideological struggle post-WWII was not against communism abroad, but at home against feminism. Men loved Bond because they knew they were losing. Indeed, feminism has won and Bond is now an exemplar of toxic masculinity, probably in need of therapy. Bond was a man’s man and this is not something our elites accept in pop culture—accordingly, the franchise has finally killed him in No Time to Die, a funny title for the pandemic years.

According to the pieties of our times, Bond is now beginning to face censorship for being, as was said of Byron, “mad, bad, and dangerous to know.” The novels are being reprinted for the 70th anniversary of Casino Royale, but now without unkind references to black people.

Perhaps the sensitivity readers—the bleeding consciences of our corporate PR—think other races less important; perhaps it’s an unfolding process of civil rights for fictional characters. Meanwhile, women must still feel the shock of Fleming’s decadent Romanticism, infamous for phrases like “the sweet tang of rape.” Intersectionality is hierarchical, after all, and it’s not yet fully structured in our entertainment.