How to Brand Yourself Today

Pick Four Traits. One of Them Must be “Victim”

I read a headline that claimed Harry and Meghan were suing South Park over its “World Wide Privacy Tour,” so I of course watched it.

It was funny: 22 minutes well spent.

But I enjoyed the episode's other main plot line better: CumHammer Brand Management. It’s a branding company that helps people cultivate a brand.

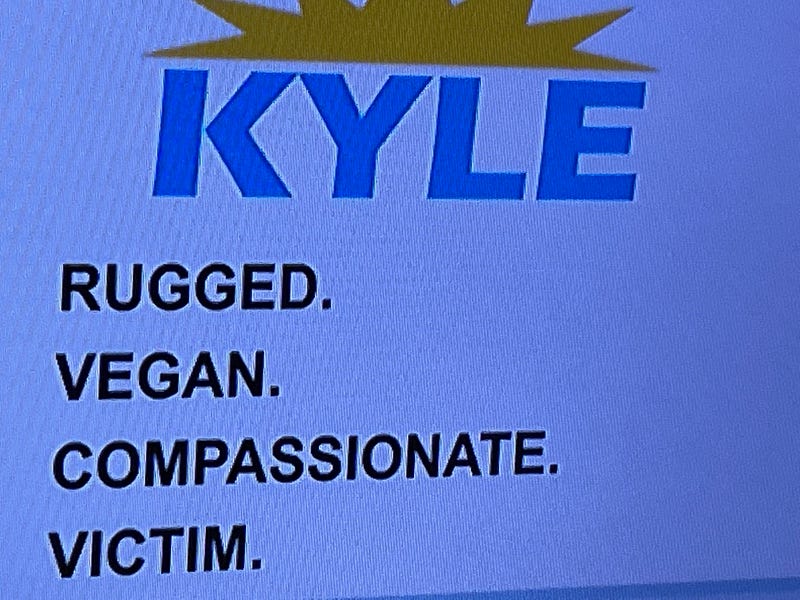

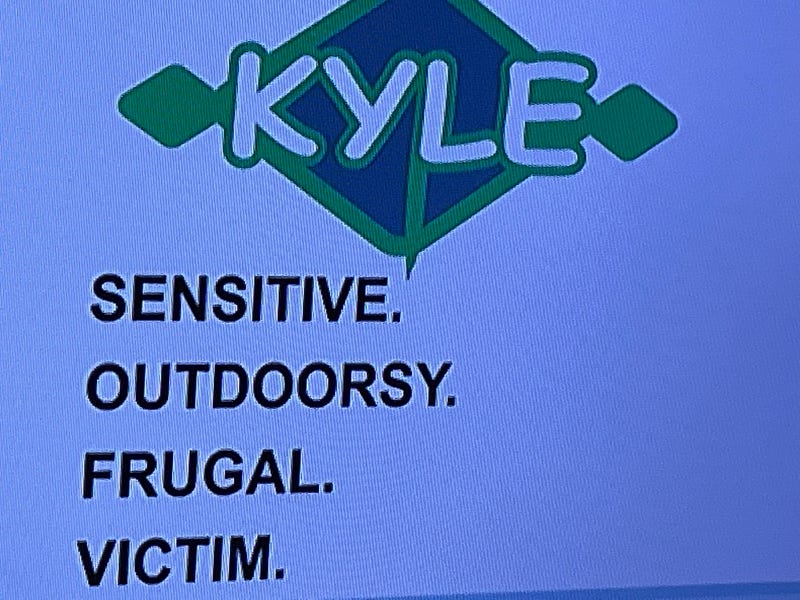

Kyle and Butters both consult with a Cumhammer brand management specialist, who presents them with different brands. Each brand has four parts. The first one suggested to Kyle is:

When Kyle rejects it, the specialist recommends:

And so on.

Every suggestion ends with “victim.”

Everyone is a Victim

We’re all tired of the “victim” spiel. The only ones who aren’t tired of it are the ones claiming victimhood, like the shockingly-privileged Meghan Markle.

But what’s behind it? Why does everyone want to be a victim?

There are the immediately-obvious reasons: it elicits sympathy, which brings focus on you, thereby gratifying your self-centeredness. It sets you apart and makes you special (or used to). It could result in speaking gigs and proceeds from your online creativity.

But why? Why would mere status as a victim be celebrated?

We Are All Victims of an Evil Structure

Shift back to last week’s column:

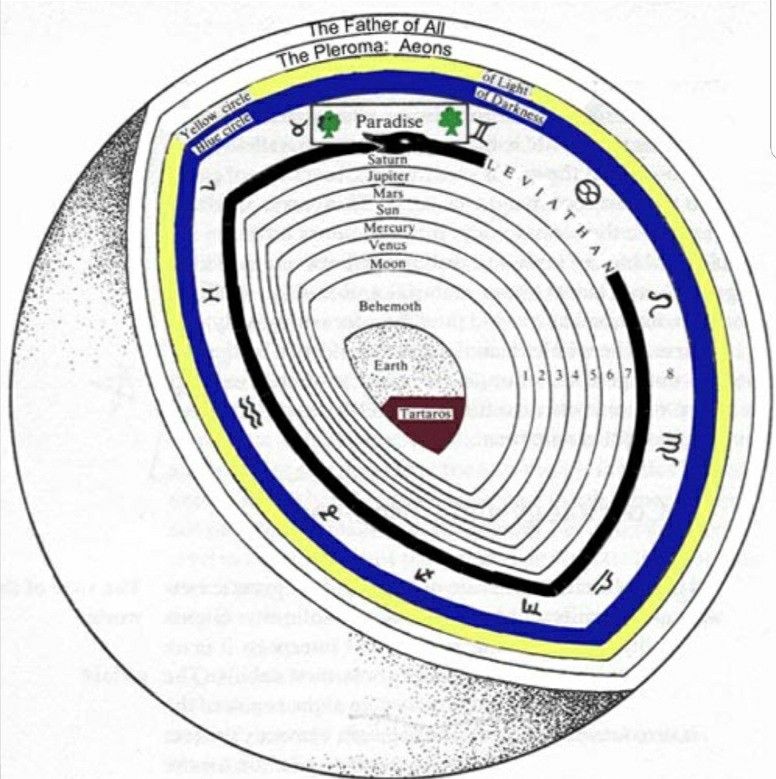

The gnostic is always battling a structure. The ancient gnostics thought an evil Demiurge set up a structure to imprison their souls. The modern Socialist gnostic thinks an economic base sets up a structure to preserve its power. The more moderate leftist gnostic thinks a structure of language arising from cultural norms creates a confining structure that privileges the people best situated to take advantage of those cultural norms.

If there’s an evil structure, there are sinister forces that support the structure: the Demiurge and his minions, the bourgeois, the white colonialists.

And there are victims of that structure: dupes who unwittingly promote the Demiurge’s prison, workers, the non-white indigenous people.

The gnostic is hard-core dualistic.

Everything for the gnostic is either/or. Everything is a binary. This pole or that pole.

To the ancient gnostic, you’re either striving against the Demiurge or reinforcing his prison by enjoying it. To the Communist gnostic, you’re either striving to end capitalism or you’re reinforcing it by making money and enjoying the fruits. To the moderate gnostic, you’re privileged and trying to keep your privileged position or you’re a victim.

Victimhood is One Example of How Our Culture is Gnostic

The prevalence of victimhood is merely cultural gnosticism in its gory.

Gnosticism, as Hans Jonas, Kurt Rudolph, Hans Urs von Balthasar, Eric Voegelin, and others have pointed out, is a religion. It’s a complete worldview, which includes the initial leap of faith into believing in something that can’t be proven, whether it’s belief in an evil Demiurge or a socio-political-cultural superstructure.

And like any religion, it has leaders and followers. It has ardent believers, it has lukewarm believers. It has believers who logically and rigorously pursue its tenets, and it has folks who don’t even entirely understand the religion but go along with it in general.

It’s that last one that is prevalent today.

“Cultural gnosticism.”

Our culture is infused with gnosticism. We think like gnostics, we use gnostic terminology, our attitude is gnostic.

I don’t even think most of us are gnostics.

But we’re culturally assimilated to gnosticism.

And that’s a major problem.

You don’t believe me?

Ask anyone, and they’ll confirm it: they’re victims.

Further Reading

Kurt Rudolph, Gnosis: The Nature & History of Gnosticism (Harper, 1987), Part Two, “Nature and Structure.”

Hans Jonas, The Gnostic Religion (Beacon Press, 1958), 42–43.