Gatsby: Grasping for Transcendence

Frank DeVito at Front Porch Republic

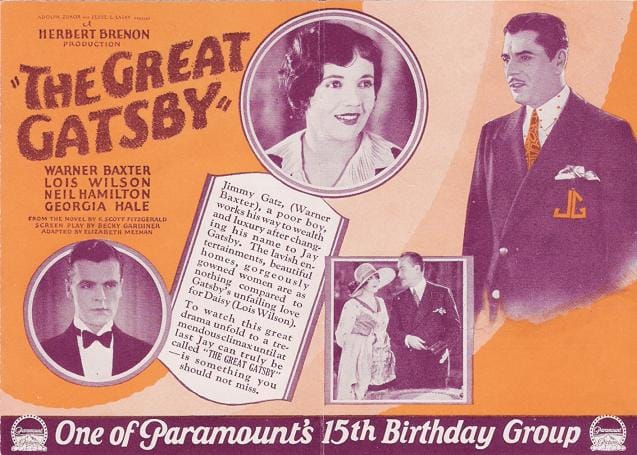

The Great Gatsby may be the greatest novel in American history. Fitzgerald takes the reader deep into the wealthy Long Island manifestation of the Roaring Twenties, an era when, according to the New York Times, “gin was the national drink and sex the national obsession.” Yet Gatsby is not merely a period piece, a myopic look at a narrow, passing period in American history. The novel is a deep dive into the world of men trapped in the box of a materialist world, where the heart continued to yearn for transcendence but the culture offered no path to fulfill such a desire. In this world, man continues to want to escape his selfishness and seek something beyond himself, but he finds no way out.

Like Gatsby—and like Fitzgerald himself—the human person yearns to “romp . . . like the mind of God,” to transcend the world of gin and sex, of mansions and parties, of the millions of dollars ready to be made here in the American Dream. But trapped in a world—the Roaring Twenties in particular, modernity in general—where one’s physical and intellectual surroundings seem devoid of God, one is in an earthly box with a depressingly low ceiling. So the restless heart seeks transcendence among the gin and sex, the mansions and parties, the millions of dollars. And such hearts will find no rest. The Great Gatsby is the story of these restless hearts.

There is a reason Gatsby is set among the great mansions of Long Island. Fitzgerald understands that, to tell the story of souls in a materialist world grasping for transcendence, it is best to tell stories of the fabulously wealthy. Those who do not have wealth and power often channel their lack of fulfillment towards the quest for wealth and power. If only they were rich, had the mansion and the cars, the high-end job, access to the rich and famous and beautiful, then they would be happy. We see these unhappy people scattered throughout Gatsby’s world: the girls downing drinks and dancing at parties to which they were not invited, the unhappy men stalking around the same parties (also uninvited, and perhaps accompanied by their wives) looking for exciting women and adventure. Created with a heart meant for greatness, for eternity, yet completely unaware of the One who can fulfill such desires, people look to fill the void with food and drink, with glitz and glam, with sex and excitement and everything else at Gatsby’s fabulous, over-the-top parties.

But watching the rich attempt to transcend their restless lives is much more interesting, because they already have all the wealth they could desire. No longer able to pin their hopes on wealth and its accouterments, they continually, desperately, grasp to transcend their circumstances somehow. What they grasp at forms a profound commentary on the human condition.

One sees the sad, futile attempts to transcend the meaninglessness of a materialist world in the lives of Tom and Daisy Buchanan. Tom Buchanan is something of a dumb man, extraordinarily wealthy with inherited money and largely unaware of what to do with himself. He found his purpose, like many young wanderers today, in sports: he “had been one of the most powerful ends that ever played football at New Haven . . . one of those men who reach such an acute limited excellence at twenty-one that everything afterward savors of anticlimax.” From there, he drifted. As an adult, Tom seems like a man who “would drift on forever seeking, a little wistfully, for the dramatic turbulence of some irrecoverable football game.”

So Tom travels the world. He buys mansions and horses and cars and everything there is to own and consume. He has affairs with women. Yet predictably, none of this fulfills him, because none of this transcends himself. Attempting to fill oneself with food and sex and experiences, to fill one’s surroundings with possessions, does not appease the longing of the human heart for something more than self. In an interesting turn from this unintellectual man, Tom attempts to find something greater than himself in worrying about the fate of “the white race” in society. In the midst of a terribly uncomfortable dinner party, where the knowledge of Tom’s affair with a woman from New York hovers over Tom, Daisy, and the guests, Tom vents about where his restlessness has taken him:

“Civilization’s going to pieces,” broke out Tom violently. “I’ve gotten to be a terrible pessimist about things. Have you read ‘The Rise of the Colored Empires’ by this man Goddard?”

“Why, no,” I answered, rather surprised by his tone.

“Well, it’s a fine book, and everybody ought to read it. The idea is if we don’t look out the white race will be—will be utterly submerged. It’s all scientific stuff; it’s been proved.”

“Tom’s getting very profound,” said Daisy, with an expression of unthoughtful sadness. “He reads deep books with long words in them. What was that word we—”

“Well, these books are all scientific,” insisted Tom, glancing at her impatiently . . . “It’s up to us, who are the dominant race, to watch out or these other races will have control of things.”

. . . There was something pathetic in his concentration, as if his complacency, more acute than of old, was not enough to him any more.

Tom has clearly hit a wall of complacency. Boxed in by a life that does not allow the transcendence that the human heart demands, Tom reaches the point where his vast wealth, his relationships, all the things he has collected, have failed him. Even this generally unthoughtful person reaches toward something beyond himself, trying to find meaning in the collective struggles of races, nations, and civilizations. Of course his attempt to do so is—like the man himself—stupid and unserious. But the grasping of this thoroughly wealthy and worldly man to seek intellectual meaning beyond himself is nonetheless a telling movement of a restless heart.

Read the rest