Gabriel Richard: The Only Saint Who Ever Served in Congress?

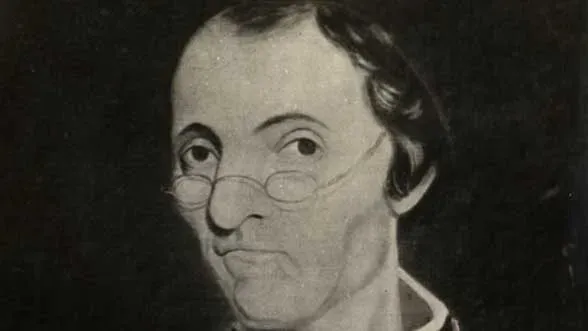

The first and only member of the U.S. Congress ever up for sainthood: Detroit’s Fr. Gabriel Richard, founder of the University of Michigan.

Father Gabriel Richard is the only member of Congress considered for sainthood out of more than 12,500 who have served since 1789.

Richard represented the Michigan Territory precisely 200 years ago (from 1823–1825), serving a single two-year term in the U.S. House. How rare is holiness at the Capitol?

“There are no saints in Congress,” presidential candidate Nikki Haley insists. For example, search “holiest member of Congress,” and the search engine asks, “Did you mean: hottest member of Congress?”

Detroiters called Gabriel Richard (1767–1832) “Le Bon Pere” or “the good father.” He achieved more in his two years in Congress than most members achieved over several decades in public office.

“The world is filled with men and women who have neglected the talents Almighty God has given them,” a Detroit tribute to Father Richard concluded 100 years after his death. “As a priest, pioneer, and patriot, he was one of the most courageous and many-sided men America has ever known.”

The city tribute added, “To his mind, his most notable accomplishment was his part in the development of Americanism in the formative years of this state and nation.”

The top 7 ways Fr. Gabriel Richard changed history on his way toward sainthood

Father Richard also bore many crosses in his 64-year life of adventures:

1. The daring way Fr. Richard escaped attackers during the French Revolution

No saint has a more inspiring story or overcame more crosses and conflicts than the French immigrant.

Father Gabriel Jacques Richard was born in La Ville de Saintes, France, on October 15, 1767.

He was ordained a priest in 1791, just two years after the French Revolution began a bloody dechristianization of France where priests (including 99 martyrs killed during the subsequent Reign of Terror) were executed.

French philosophers like Denis Diderot (1713–1784) encouraged violent revolt against all authority figures (particularly royalty and Christian clergy) by declaring, “Man will never be free until the last king is strangled with the entrails of the last priest.”

Young Father Richard refused to comply with the revolutionary demands, so he fled to America to become a missionary priest, leaving France in 1792.

He escaped arrest by jumping from a second-story window, scarred for life when a neighbor threw a metal teapot at him, hitting him in the face.

2. Bridging divisions in the New World

By the end of the 18th century, he arrived in Detroit, a hub of the Old Northwest Territory serving the parish that grew into the Basilica of Sainte Anne de Detroit.

The second-oldest continuously operating Roman Catholic parish in the United States was started the day after French settlers established Detroit in 1701. By 1798, Detroit was already a divided city:

The French lost Detroit to the British, who turned the area over to the new United States government. This frontier town was a mixture of Americans, French settlers, British colonists, and Native Americans.

In 1801, when Detroit had a population of 2,000, he welcomed a bishop to complete 501 confirmations representing 25 percent of Detroit’s population, confirming Catholics from age 13 to 80 over four days.

The “good father” had to find a way to bring them together in a parish whose boundaries stretched from Toledo, Ohio, to Duluth, Minnesota.

Protestants also asked Father Richard to preach to them, and he did, focusing on topics where Catholics and Protestants were like-minded.

3. The great fire and a new resurrection: It will rise from the ashes

In 1805, a great fire destroyed Detroit, leaving nothing but the chimneys. Father Richard inspired a third of the people (who were considering leaving the area) to stay and rebuild.

Father Richard led the efforts to rebuild Detroit and its Church.

He gave the city its motto, two Latin phrases describing a history of future rises and falls of the region and its auto industry. Chrysler featured the motto in a 2012 Super Bowl ad, while Ford splashed the motto in light when it took over the city’s abandoned railroad station:

“We hope for better things; it shall arise from the ashes.”

4. Defying enemy invaders

During the War of 1812, Detroit (then Michigan’s capital) was invaded by the British, who took control of the city without firing a shot.

That embarrassment inspired the state of Michigan’s subsequent motto, “Tuebor,” which means “I will defend,” a vow that Michigan would never surrender to enemy invaders again.

While the state surrendered, Father Richard would not yield. Finally, the British captured Father Richard, and when they demanded a loyalty oath, he refused the demand the way he did with the French revolutionaries.

He said he’d already given his loyalty to the U.S. authorities and told the British, “Do with me as you please.’’ Others followed his example, so the British imprisoned him.

But Chief Tecumseh of the Shawnee Tribe said he and his warriors wouldn’t support the British until the respected Father Richard was released, so the British set the priest free.

5. Fighting for Michigan education, the first newspaper, and the University of Michigan

The perfect example of education and innovation coming at the intersection of disciplines?

A federal judge, a Presbyterian minister, and Father Richard, a Catholic priest from France, joined forces to create the University of Michigan, one of the nation’s first and most respected public universities.

Richard fought for education and growing public knowledge for most of his career. Finally, he got a printing press to start the state’s first newspaper.

His first letter to a U.S. president went to Thomas Jefferson, the author of the Declaration of Independence and the third president of the United States, fighting for support for new schools — for all.

He established specialized schools for all ages, including specialized education for deaf children, Native Americans, and, most importantly, the University of Michigan:

- His “school for all’’ was open to the children of the U.S. settlers and Indian tribes alike.

- In 1825, he established the first classes for the deaf.

- The original University of Michigan included a grade school for young children and a pre-seminary establishing a “whole education system” concerned with “knowledge of all things,”

Judge Augustus Woodward, Rev. John Monteith (who lived in Detroit for five years from 1816–21), and Father Richard developed the 1817 plan for U-M modeled after the University of France. Monteith was named president, and Father Richard was vice president, with all 13 of the original professorships being divided between Monteith and Richard.

The legislation authorizing U-M passed on August 26, 1817, and the cornerstone was laid on September 24.

Five days later, as a tribute to Father Richard’s service to Native Americans, the native Chippewa, Odawa, and Potawami tribes ceded 3,840 acres of land, with half earmarked for supporting the new University and the other half for the support of Father Richard’s Ste. Anne’s Church.

So the University of Michigan’s first endowment came from Native American tribes making a gift to the French immigrant priest.

The University Act of 1821 reorganized the University (dubbed initially the Catholepistemiad or University of Michigania) as the University of Michigan.

Montieth moved to Ohio that same year, but Richard served on the U-M board until he died in 1832. Five years after Father Richard’s death, U-M was reorganized in its current home, Ann Arbor.

6. Elected to Congress so he could donate his salary toward the building of a new Church

Father Gabriel Richard was elected to Congress to represent the vast Michigan Territory in 1823, precisely 200 years ago.

Because Michigan wasn’t a state, he lacked voting power but still managed to do more than most members of Congress achieve today.

Richard immediately presented 16 petitions to the 18th Congress and secured support for the first federal road from Detroit to Chicago, Michigan Avenue, now U.S. 12.

A year after his petition for a road crossing the whole territory, the highway was established in federal law and surveyed by the end of 1825. Construction started in 1829, and the road was finished across Michigan in 1833, four years before Michigan became a state.

7. Father Gabriel Richard died fighting to save and comfort people during a pandemic

The time of cholera, a massive global pandemic, hit Detroit in 1832. Richard worked tirelessly ministering to cholera victims until he became one of the last Detroiters to die during that pandemic.

He was pale and emaciated at the end, exhausted from going house to house, encouraging people who were well while helping needy patients.

More than 2,500 people (greater than the entire population of Detroit at the time) attended his funeral.

A century after his death, Detroit honored Father Richard in the 1930s, 1940s, and 1950s with all-day celebrations. In 1960, a failed effort to save Detroit’s old City Hall (opened in 1871 and leveled in 1961) included a plea to move Father Richard’s body there.

As he died on September 13, 1832, Father Richard received the Blessed Sacrament a final time, saying, “Lord, now let thy servant depart in peace, according to thy Word.’’

Learn more or support the cause at the Father Gabriel Richard Guild.

Used with permission from Joseph Serwach, who is not otherwise affiliated with TDE. This essay originally appeared at Medium.com