Flannery O’Connor on Sin and Politics

By Darrell Falconburg From The Imaginative Conservative

It has been often repeated that The Times of London once sent an inquiry to famous authors, asking them the question, “What is wrong with the world today?” When G.K. Chesterton received this inquiry, he had an interesting yet unsurprising response. He did not blame the world’s dysfunction on some external problem — not on a president, an economic program, a political party, or anything else. And, on top of that, he did not take the opportunity to put his political or economic views into the pages of the Times. He knew that the dysfunction of the world runs far deeper than politics. What is wrong with the world, he knew, is sin. Chesterton therefore responded rather simply: “I am.”[1]

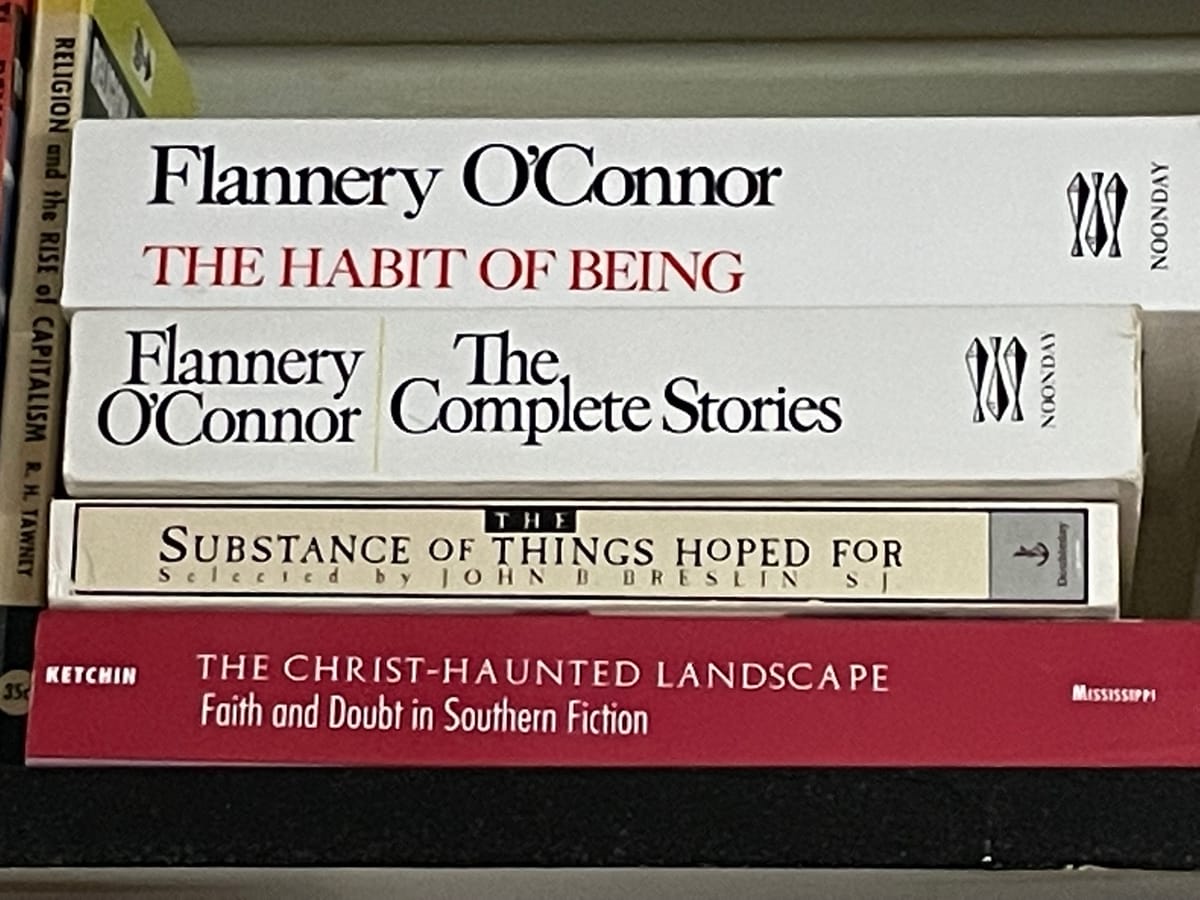

I was recently reminded of Chesterton’s response while reading my way through parts of The Complete Stories of Flannery O’Connor. Much like Chesterton, Flannery O’Connor understood that what is wrong with the world is not our failure to adhere to a certain political or economic program, as important as these may be. Instead, what is wrong with the world is sin. Therefore, if we are to reform society through politics, it is first essential to reform ourselves. O’Connor conveys this in her short story “Everything That Rises Must Converge.” The reformer must realize that he, not someone else, is the only source of evil in the world that he can control. Then, upon realizing that he is the only source of evil that he can control, the reformer must begin the journey of personal reform that must precede the reform of those around him.

Flannery O’Connor on Sin and the Human Heart

As a Roman Catholic, Flannery O’Connor did not believe in John Calvin’s doctrine of total depravity. She did, however, emphasize man’s sinfulness throughout her stories. Man is fallen, believed O’Connor, and he is capable of great wickedness. Any serious Christian writer must therefore make the reality of man’s sinfulness a bedrock of their story. O’Connor writes:

“The serious writer has always taken the flaw in human nature for his starting point, usually the flaw in an otherwise admirable character. Drama usually bases itself on the bedrock of original sin, whether the writer thinks in theological terms or not. Then, too, any character in a serious novel is supposed to carry a burden of meaning larger than himself. The novelist doesn’t write about people in a vacuum; he writes about people in a world where something is obviously lacking, where there is the general mystery of incompleteness and the particular tragedy of our own times to be demonstrated, and the novelist tries to give you, within the form of the book, the total experience of human nature at any time. For this reason, the greatest dramas naturally involve the salvation or loss of the soul. Where there is no belief in the soul, there is very little drama.”[2]

A fundamental truth about man, especially modern man, is his sinfulness. This flaw in human nature is, for O’Connor, a common theme in all of her stories. As Jessica Hooten Wilson notes, O’Connor’s characters are often confronted with the flaws of their human nature by becoming aware, however painful it might be, of what they lack. And what these characters often lack is the self-knowledge that they are prideful and self-righteous, that they are sinners. In this regard,

O’Connor conveys something true and timeless in her stories: that we humans are contaminated by sin and, as a result, must come to a self-knowledge about what we lack.[3]