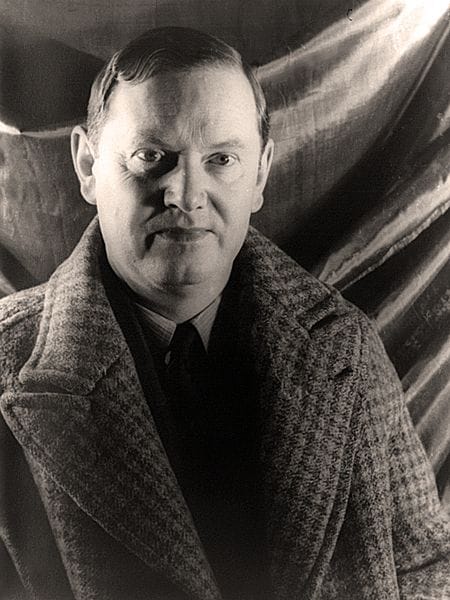

Evelyn Waugh: A Life Revisited

Paul Mankowski at First Things

Arthur Evelyn St. John Waugh was born in 1903 to upper-middle-class Anglicans who lived in a suburb of London. He attended a boarding secondary school (Lancing College), read history at Oxford, published his first book (a biography of the painter Dante Gabriel Rossetti) at age twenty-four, then his first novel a year later. Waugh married that same year (1928), divorced after two years, and converted to Catholicism. After the first marriage was declared null, he married a Catholic by whom he had seven children. He served honorably but ineffectively as an infantry officer in World War II, and was to publish thirteen novels, as well as seven travel books, three biographies, a volume of autobiography, and numerous essays and book reviews. Lionized in the 1920s as a trendy man of fashion, he became increasingly conservative in politics and churchmanship and notorious for his truculent contempt for the sham enthusiasms of modernity. He died on Easter Sunday, 1966, at his house in Somerset.

In addition to works published in his lifetime, Waugh left behind several hundred pages of diaries and thousands of letters. And in reading these we become aware that sometime between the ages of fifteen and seventeen, he acquired an almost freakishly mature mastery of English prose. For the remainder of his life, he was all but incapable of writing a boring sentence. Even in his commonplace and perfunctory communications—business correspondence, military reports, letters to agents and headmasters—Waugh wrote a clean, elegant, beautifully precise English that is appetizing in the most unpromising circumstances. Just as it’s unsettling to be reminded that Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier was a set of keyboard exercises composed “for the profit and use of musical youth desirous of learning,” it’s remarkable how much eerily flawless craftsmanship Waugh displays even when the occasion of his writing is casual or mundane.

The most outstanding characteristic of Waugh’s prose is its lucidity. Every sentence is clear. Even where his subject matter is thorny, I don’t believe I’ve ever had to read a sentence twice over to get its meaning. His friend and fellow novelist Graham Greene remarked that what struck him about Waugh’s writing was its transparency, that you could see all the way to the bottom, as with the Mediterranean in days gone by. This transparency is partly attributable to perfect syntax—grammatical solecisms are almost nonexistent—and partly to Waugh’s care in choosing the right word, the word that not only conveys but illuminates. Sometimes Waugh employs a recondite word from his compendious vocabulary, but never an obscure word for the sake of its obscurity. As a boy I learned the meaning of many words I had never before encountered from the perfect fit they were given by Waugh in a single memorable phrase. Reading Waugh, you don’t need a dictionary at your elbow; the sentence provides sufficient light on its own.

Waugh also had a genius for conveying spoken English matched only, perhaps, by James Joyce. Like Joyce, he lets us hear the speakers through their dialogue—their accents; their treble or contralto, their coughs, stammers, and lisps; their whining or their barking—and he does this with almost no departure from standard spelling. We recognize cockneys without resort to dropped aitches and Scotsmen without resort to tripled r’s; we recognize them because the speeches Waugh gives them convince us that only this cockney or only this Scotsman could utter them. Their language informs us about his characters’ class, age, education, and provenance with a certainty that makes further description superfluous. So too their brief speeches give us a glimpse into his characters’ souls that clumsier authors would require many pages of narrative to communicate.

Almost miraculous in this respect is Waugh’s first novel, titled Decline and Fall, whose minor characters, though mere props in a farce, have a kind of inevitability and immortality: Once having read the lines Waugh gives them, you can’t imagine their ever saying anything else. Something imperishable has been created out of nothing. You feel you’d know Dr. Fagan and Lady Beste-Chetwynde were you to overhear them in a bus. The quality persists in Waugh’s later works, but only sporadically and only in the minor characters.

A third characteristic of Waugh the prose stylist is the concord between the rhythm of the paragraph and its meaning—a concord that is easier to perceive than it is to analyze. By the operation of some deep poetic instinct, the rise and fall of the narrative augment and reinforce the sense of the words that underlie it. Here is one example, from the travel book When the Going Was Good, describing an encounter with a young American on a lake steamer on the way to the Congo:

I offered him a drink and he said “Oh no, thank you,” in a tone which in four monosyllables contrived to express first surprise, then pain, then reproof, and finally forgiveness. Later I found that he was a member of the Seventh Day Adventist Mission, on his way to audit accounts at Bulawayo.

As with Edward Gibbon, every sentence in Waugh has a kind of architectural perfection; as did Gibbon, Waugh knew how to maximize the blunt impact of the monosyllabic word by its well-timed departure from a stream of elegant polysyllables. Waugh strove for economy of expression, such that the structural elements of this prose would each carry as much weight as possible. He frequently compared the writer’s craft to that of a cabinetmaker or carpenter, and saw the joinery of words as an indispensable task of artisanship. In a 1949 letter to Thomas Merton—who had sent him a draft of his book The Waters of Siloe—Waugh criticizes the monk for shirking this chore:

The Seven Storey Mountain

Waugh loathed the pretense of artists as members of a secular priesthood, and insisted that exalted art did not exist apart from the humble craftsmanship that was a necessary, but not a sufficient, condition of its existence.