C. S. Lewis, J. R. R. Tolkien and the Inklings: Telling Stories to Save Lives

By Rachel Lu: America Magazine

Envy is a sin, but it can be hard not to feel a twinge just looking across the Atlantic, contemplating the great tradition of English storytelling. Even in childhood, I wondered why so many of my favorite books involved tuppence candy, seaside holidays and school children racing home for tea. My girlhood shelves were stuffed with volumes from Roald Dahl, Beatrix Potter, Robert Louis Stevenson, J. M. Barrie and Lewis Carroll. With my own children, I have also discovered the works of Arthur Ransome, J. K. Rowling and Hillaire Belloc. There are some fine American children’s authors too, but somehow the old country seems to have the edge.

At the center of this great pantheon, we find the Inklings. For generations now, these great Oxford storytellers have drawn the whole world to their crackling hearth. C. S. Lewis’s Chronicles of Narniahave sold more than 100 million copies worldwide. J. R. R. Tolkien’s novels, by some estimates, have sold an astonishing 600 million copies. Both authors have been translated into more than 40 languages. They continue to provide rich content for film and television, as we see in the new Amazon series based on The Lord of the Rings.

They led an immense number of souls to Jesus Christ. Passionate fans will sometimes insist that Tolkien’s work is “not Christian allegory,” which is true enough as far as it goes. Unlike, say, The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe, it was not meant to be explicitly allegorical. Nevertheless, Tolkien’s work is deeply suffused with his deeply Catholic sensibilities, and readers do absorb those, whether or not they recognize the implications. As an adult convert to the faith, I find it remarkable how often I hear both Lewis and Tolkien mentioned by fellow converts as critical influences. Neither has been canonized (and Lewis was a member of the Church of England), but as modern-day evangelists they are simply unrivaled.

How did they do it? Who were the Inklings? The second question may help us to answer the first. The Inklings is the name of an informal literary club that met at Oxford in the mid-20th century. From roughly 1933 through 1949, they gathered each Thursday night in Lewis’s rooms at Magdalen Hall to hear and critique one another’s work. Compositions were read aloud by their authors. Discussion and critique would then follow. As intimate friends, the Inklings shared many other favorite pastimes: taking long walks, giving or attending lectures, eating and drinking together at the local pub. Like hobbits and Narnians, they loved their simple pleasures. The real work got done at the Thursday night meetings, however. In those hours, their dynamic friendship flowed over into something transformative.

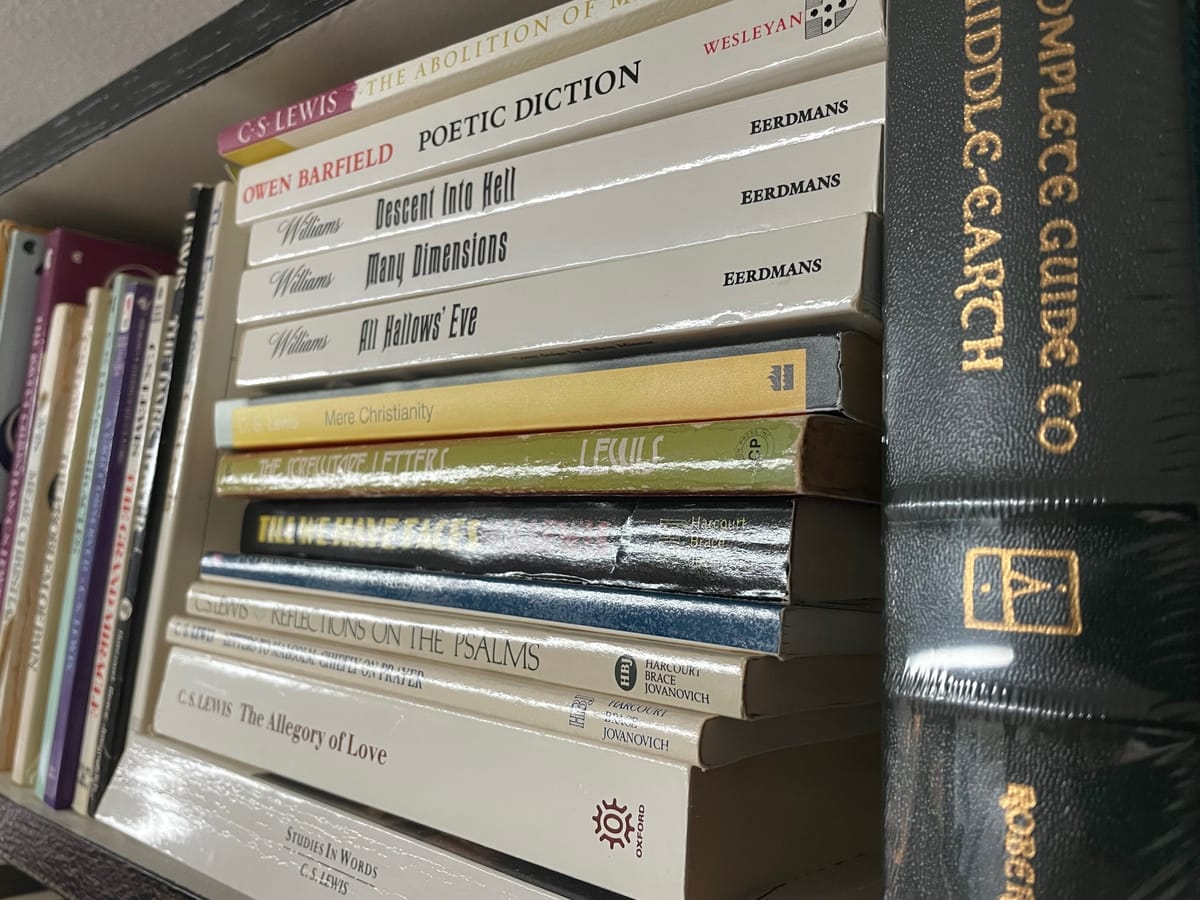

Beyond the most famous two members, a few others are worthy of mention. Charles Williams, an editor at Oxford University Press, had a sanguine temperament and a luminous mind. His death in 1945 was a particularly sore blow to the group. Warren Lewis, the elder brother of Clive Staples, was a dedicated member who played a particularly invaluable role by keeping careful notes on the Thursday meetings across the years. Owen Barfield, an old friend of C. S. Lewis, resided in London but dropped in on the club whenever he was able. Both Catholics and Protestants participated, but all were united in a quest to defend and revitalize Christian culture in a world that seemed to be abandoning it.

They were not especially well-traveled or urbane. They came from ordinary middle-class families. Except perhaps for Williams, none was particularly known for personal charisma. On some level, the Inklings were just a clique of fusty old English intellectuals, possessed of none of the savvy instincts that we associate today with “influencers.” But if the club itself was not diverse, the readership certainly has been. Somehow these men transcended their own times and circumstances, translating Christian ideas into a language that everyone wanted to hear. There are lessons here for writers and creative artists, and indeed for all Christians who would place their gifts and talents in God’s hands, to be used for building the kingdom. The Inklings had a talent for friendship, but also a particular genius for making old things new. We need to relearn this art.