Bottled and Unsalivated

From The Lamp

For the simpler—and considerably more commonplace—pleasures of everyday life in most parts of the world, beer has no peer. Because it can be locally produced almost anywhere, it has a more universal reach than even the cheapest mass-produced wines. Whether you’re an African miner or farm laborer, a solid Bavarian burgher, a Japanese accountant, an English lager lout, a Brazilian gadabout, or a Middle American watching the Super Bowl with friends and family, beer is the ultimate social drink. More so than wine, it is a relatively mild, nourishing beverage that fosters a soft, slow glow of affability in most sane imbibers.

There’s nothing brooding or introspective about a typical beer buzz. Beer seems to lend a little of its own effervescence to the mood of those who drink it. It’s a sociable drink for social drinkers. This has been understood and appreciated by a broad spectrum of societies and cultures around the world that often agree on little else. You could say that beer is as old as history itself, except that it’s considerably older. There is conclusive archeological proof that it was being brewed and consumed in prehistoric times. Indeed, the earliest scientific evidence of beer was found in a cave in Israel dating from 11,000 B.C., a good four thousand years before humans had begun to grow grain domestically or developed pottery containers to carry beer from one place to another.

All of this is chronicled in Professor John W. Arthur’s Beer: A Global Journey Through the Past and Present. The author has done a pretty good job of telescoping a very big story into a rather small book: two-hundred ninety-four pages in all, but only one-hundred ninety-three pages of actual text, the rest being given over to professorial glossaries, appendices, re-imagined recipes of ancient or arcane brews, and a running river of footnotes. Aside from an introductory overview and terminal essay, Professor Arthur draws on his own scholarly research and field work, as well as the writings of numerous historians, archeologists, and anthropologists, to tell the worldwide story of beer. He divides his beer history into four regionalized chapters the titles of which hint pretty broadly at their content: “The Near East and East Asia: Funerary Stone Pits, Red-Crowned Crane Flutes, Ancient Hymns, and Bear-Hunting Rituals”; “Africa: Where Beer Feeds the Living and the Ancestors”; “Europe: Ancient Henge Rituals, Beer Beakers, Celtic Funerary Urns, Vikings and Witchcraft”; and “Meso- and South America: Beer Fuels Runners, Roads, and Feasts.”

Learned twaddle about urns, beakers, and rituals aside, however, the most obvious reason why beer has been so popular for so long all over the world is that PEOPLE LIKE TO DRINK IT. There is, however, another important factor. It is almost as easy to make beer as it is to guzzle it. All it takes is water, almost any sort of grain or grain blends, yeast, and a little patience. No terroir, no ancient vines, and a minimum of refined mumbo jumbo.

This helps to explain why, throughout the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, a universal beer norm was established throughout the western and colonial worlds. Whether you consider this civilized progress or one more crime perpetrated by imperialist-colonialist oppressors, the facts are the same. Wherever European explorers, conquerors, settlers, or immigrants went during this period, they brought their beer with them. And modern breweries soon followed, almost universally presided over by German or “Austrian” brewmasters, the latter usually Czech subjects of the old Austro-Hungarian Empire.

Wherever these brewmasters went, they produced what the Germans called lager and the Czechs called pilsner. Both were smooth, pale amber-hued, frothy beers of the sort that still outsells all of the good, bad, and just plain peculiar “craft beers” produced by trendy boutique operations today. Don’t get me wrong. Some of today’s craft brewers are true masters of their art and have produced a lot of good pale India ales, wheat beers, and the like, but there are others who approach brewing as if they were designing bizarre new ice cream flavors for Ben and Jerry’s. They sometimes remind me of the teenage girls of an earlier era who used to order cherry, chocolate, or vanilla-infused Cokes at drugstore soda fountains, in those long-gone days when most drugstores still had soda fountains. Who knows? Perhaps some future Professor Arthur will explain to readers how the rise of “flavored” craft beers in America was largely due to the disappearance of soda fountains, a phenomenon akin to modern humans replacing Neanderthal man.

Other evolutionary phenomena involving beer are less speculative and more fact based. To cite a prime example, until Prohibition, almost every American city had one or more large breweries. Their owners, along with those of local department stores, bakeries, and newspapers, were often the wealthiest and most respected members of the community. Then came Prohibition. Many of the breweries that were shut down at the time never reopened. Others diversified, producing products such as ice cream, soft drinks, and near-beer as a temporary survival strategy. Most of these lived to see the repeal of Prohibition—one of the few parts of F.D.R.’s New Deal that can qualify as a total success.

Beer was back, but there were new problems clouding the horizon. By the early 1960s a handful of nationally-marketed mega-brands (in those days Budweiser, Schlitz, and Miller at the premium level) dominated the national beer market. Many a local American brewer felt threatened rather than inspired by the sight of the legendary Budweiser Clydesdales clopping down Main Street in Fourth of July parades and promotional events. Their fears were warranted as more and more local and regional brewers either went under or barely hung on by underselling the big national brands, all too often with increasingly inferior products.

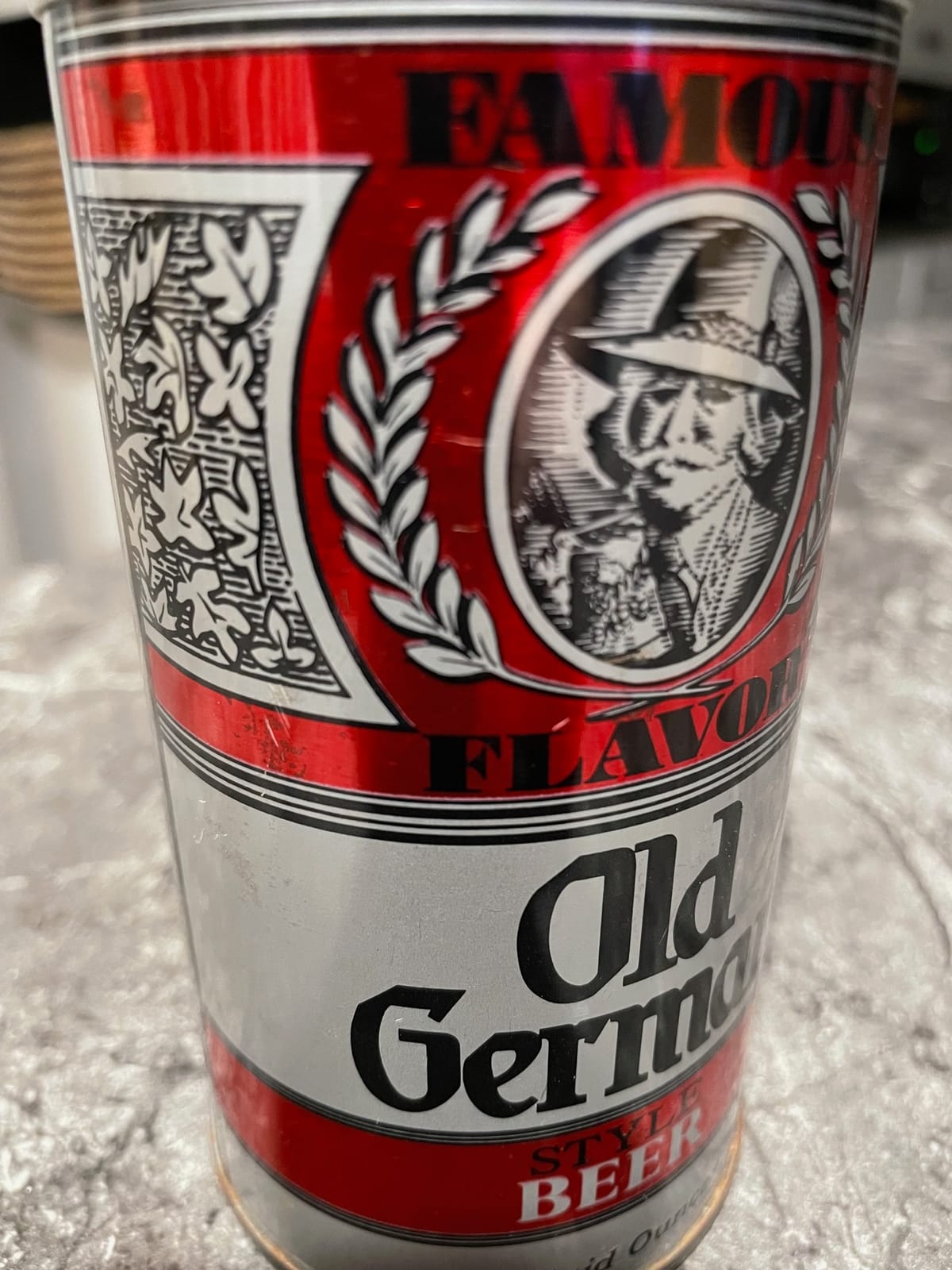

I still shudder at the recollection of a Washington-area brand during the late 1950s, Old German, brewed in Cumberland, Maryland, which sold at the incredibly low rate of eight bottles for a dollar. Unfortunately, it tasted as cheap as its price and, if you were forgetful enough to leave a not-quite-empty bottle of the stuff in a dark corner of the garage, attic, or basement recreation room, you sometimes found things growing out of it a few days later.

At least two old regional or local breweries elsewhere have bucked the trend and not only survived but thrived.