Books Can Shield You From Cults

Role models are great. We all oughtta have a few.

But don’t underestimate the anti-role models. These cautionary wraiths of consequence are more often the true educators in this carnival of folly called “modernity,” whispering not “be like me” but “For God’s sake, be anything but.”

That lean 60-year-old man playing robust basketball inspires, but that 60-year-old Marlboro Man wheezing up a half flight of stairs indicts. Self-immolation feels good when the consequences are 40 years down the road, but it don’t look so swift in real time.

Or consider the demure lady on her park bench, peacefully lost in the hush of printed pages amid the twittering pigeons and distant snarl of traffic.

Then contrast her with the Zizians, those spectral acolytes of deranged online oracles, their eyes glassy from marathon sessions of screen-glow, their minds sharpened to razors but unmoored from any ballast. These folks don’t merely warn us about the dangers of online reading: they embody the danger of dancing along the edge of the digital abyss.

Ziz herself1 read a lot, plucking her nom de guerre from the fever-dream bowels of Worm, that interminable 7,000-page web serial disgorged onto WordPress from 2011 to 2013 that the rationalist hordes lap up as holy fictional writ.

Before she was 25—the age when the cranium finally seals its leaky hull against the tempests of youth—Ziz had also mainlined the output of Eliezer Yudkowsky’s endless blog, those screeds later bundled into the 2,100 page Sequences that became the online summa of super-rationality.2

She devoured it, pixels and all.

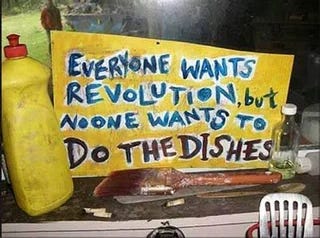

In the definitive account of the Zizians, Oliver Conroy writes that the Zizians were “smart but not always wise” and they spent “dizzying amounts of time on the Internet” and reading massive amounts “by the glow of a computer screen.” They were idealists aflame with the riddles of rogue algorithms, says Conroy, and “too fired up solving the alignment problem to do dishes.”3

We are all, Adam Lehrer pointed out, just one errant hyperlink from another cult.

Let’s be as blunt as possible without vulgarity: Online reading is the Cartesian curse incarnate. Mind yoked to mind across a sterile void, brain severed from the rude mechanics of body, information zipping from server-farm to synapse like a telegram from the void. No mediation. Heck, no mercy. Just the cold relay of ones and zeros. Impersonal as porn.

Now, a physical book? That’s a different sort of leather.

Your arms become bridges, your hands the anchors. You heft its spine, you touch the pages, you sometimes rest it on your chest like an infant. Try that with a laptop. Kinda possible, just like it’s kinda possible to have sex with a robot, but don’t porn yourself: the laptop, no matter how intimate you think you are with it, is a slab of alienation. The book, meanwhile, roots you in the soil of sensation, calms the interior mental gale, and throttles back the frantic tick of the second hand.

The screen? All contrasts: It excites, it goads, it accelerates.

Careful reading—what Albert Jay Nock referred to simply as “reading” and what our ADD-riddled age fumbles to recover with phrases like “deep literacy”—hones the discursive reason and the ability to make logical inferences and arguments, tools that equip you in the gritty areas of real life of production and survival beyond the page.

Admittedly, online reading does the same thing.

But it does it too well.

It’s hyper-rational, hyper-logical, and hyper-productive. It’s rationality of the sort that revved Chesterton’s maniac, it’s logic to the land of lunacy, it’s as productive as a Ponzi scheme.

Don’t mistake me, now. The Zizians likely arrived at the keyboard with their minds already bent, at least a little, just as the gym rat who eyes the steroid syringe for the first time is already unhealthy at some level. The screen, like the needle, merely fans the embers of instability into a bonfire; it doesn’t plant the dry tinder in the first place.

Nor would a shelf of leather-bound tomes have rescued them from the plunge. Eric Voegelin, that sage dissector of gnostic fevers, reminded us that the cult’s hallmark is the koran—the one sacred text, the ur-document that binds the faithful in ecstatic delusion. Until recently, that totem was always a physical book, that thing I’ve been celebrating in these recent essays.

And yet!

There’s an alchemy in the physical book that no algorithm can ape. I swear it by the ink stains on my fingers. Try it yourself: sit with a book, feel its weight settle like an old friend’s hand on your shoulder, and mark how the pulse steadies, the breath deepens, the skull’s relentless static fades.

Then plop your mangy selves before the screen and witness the inverse rite: the heart jackhammers, the lungs shallow out, thoughts start racing.

The contrast is subtle as a fault line, but seismic in its verdict.

Not every soul who mainlines online prose will spiral into the cultic, any more than every chain-smoker coughs up a tumor by forty. The roulette wheel spins unevenly; some dodge the bullet through sheer dumb luck or iron constitutions.

But that doesn’t change a basic fact: they’re both arsenic in the well. They’re slow poisons guzzled under the guise of progress.

Shun the Zizian path.

Ditch the digital cigarette.

And for the love of all that’s analog and alive, set down the glowing idol. Pick up a book. Let its pages remind you that the world still turns on hinges of paper and patience, not hyperlinks and hubris.

Link to same essay at Substack