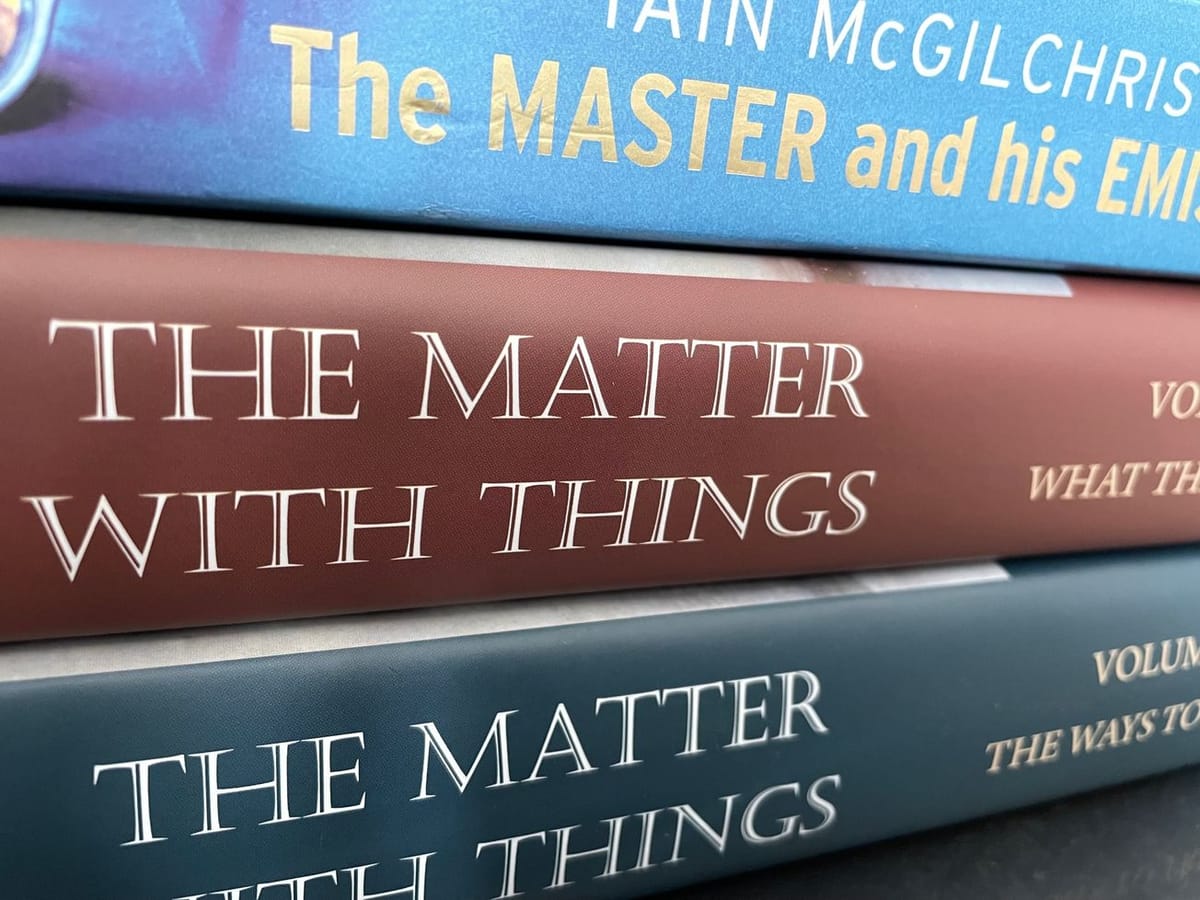

Beyond the Scientific Revolution: Ian McGilchrist’s “The Matter With Things”

Richard Cocks at VoegelinView

While the scientific revolution produced many benefits, the scientific perspective omits purpose and value, without which life is meaningless. With The Matter With Things, Iain McGilchrist makes a valuable contribution to the body of poetry, literature, psychology, and philosophy that has rebelled against scientism and sought to give a more expansive, spiritual, and humane view of us and the cosmos. His deep understanding of the way the left and right hemispheres of our brains deal with the world provides a useful framework for thinking about what gets left out of the scientific worldview. Even were the hemispheric differences to be understood as a metaphor, and they are far more than that, McGilchrist has provided a vocabulary for referring to things which are by their nature hard to express or point at. The process began with The Master and His Emissary but is taken much further with The Matter With Things. Interestingly, some of what has taken place culturally and linguistically has rather exact parallels in the realm of madness and developmentally derived mental pathologies. His fellow psychiatrist, to whom McGilchrist appeals, Louis A. Sass, author of Madness and Modernity, concurs. The cynics and skeptics, those lacking imagination, those convinced that humans are robots and nothing more, have the easy task of heaping contempt on those of us who are none of those things. This teenage mode of asserting one’s superiority; the ones who consider themselves willing to face the truth that man is “nothing but” a mechanical doll; a collection of atoms and molecules following its programming, resembles, in significant ways, the schizophrenic, the autistic, and the psychopathic. The first two, at least, have trouble recognizing the reality of both themselves and other people. The right hemisphere is responsible for our intuitive sense of the reality of the world around us, and this sense can be compromised when things go wrong and these abilities are harmed.

Majoring in analytic philosophy, for the non-autistically inclined, can indeed feel like entering a madhouse. The apparent message? Life is far less interesting than you think it is. Professors strip any meaning, significance, or interest from any subject to which they turn their minds. “Writer” in Andrei Tarkovsky’s movie Stalker, avers that UFOs, telepathy, and the Bermuda Triangle do not exist. Everything is boring. And, if it turns out that alien civilizations exist, they will be boring, too. Writer might be right about UFOs, etc. But, anything that excites the imagination and produces wonder can be good if taken in the right way. King Arthur and Atlantis might or might not be fiction, but what material they give us to ponder! To what other thoughts may they lead?

Zamyatin’s We has much the same critique of the left hemisphere preferences of certain types of people. Having initially supported the Russian revolution, three years of living under Lenin’s dictatorship enlightened him as to the error of his ways, and We was his response. It was immediately banned – indicating that it hit rather too close to home. In Zamyatin’s dystopian novel, everything is to be rational and planned. Crooked roads are to be made straight. Anything natural or wild is to be walled off and happiness is to be achieved by making it compulsory. Those parts of the brain leading to questioning the order imposed on the population, or wishing to escape from rigid thinking and regimentation, were to be surgically removed. And which part was that? The imagination.

The truly great cultural changing scientists exhibit imagination in spades. They use their intuition, insight, inspiration, and creativity – all the things the lesser scientists and their philosophical followers despise – either overtly or in practice. McGilchrist has copious quotations from those geniuses decrying their narrow-minded and less able brethren, though their chidings seem to do no good.