Albert Jay Nock, the Remnant, and Our Need to Read

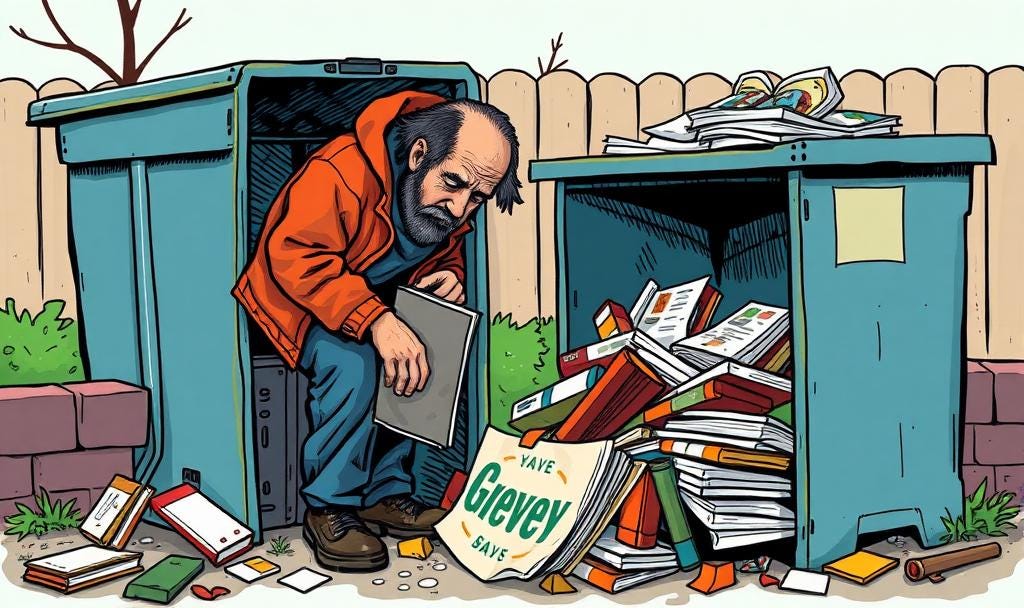

Picture a man, tattered coat flapping, rummaging through a dumpster in an alley. You wince, don’t you? That flicker of disgust ripples through your gut.

But hold on. Don’t judge him too harshly. He’s not much different from a stray dog, sniffing for scraps.

That’s not my line; it’s Albert Jay Nock’s, that old curmudgeonly godfather of the modern libertarian movement.

Nock used to gag at such sights himself, till one day it hit him: morally, that dumpster-diver is no better than a hound. No point in judging what’s just instinct wrapped in rags.

It’s a brutal thought, but Nock didn’t sugarcoat.

He put humanity into two groups: the rare few who climb toward something higher—call them Sophocles, Saladin, Shakespeare, or their kin—and then the rest, the great unwashed, still largely Neolithic, scarcely improved from a Paleolithic hunter-gatherer.

Nock pegged the first group, his “Remnant,” at maybe 10% of mankind. The rest? Stuck in 5000 BC, working with crude wooden implements and scratching in the soil.

It’s a snob’s view, no question, and it stains the later pages of Nock’s thought like spilled ink.

But he wasn’t entirely off the mark.

We’re all sitting on a spectrum—Neolithic man at one end, delighting over his first plow, and at the other, Socrates or St. Francis, gazing into transcendence.

The only question is: what drags a soul toward one pole or the other?

It ain’t brains, that’s for sure. Nock tipped his hat to clever scientists and industrial tycoons like Edison and Ford, but placed them on the Neolithic side of the spectrum. Nor is it money, status, church membership, or a fancy degree.

I’m pretty confident Nock never defined the Remnant. He simply said the Remnant aren’t the the masses. The Remnant don’t sway with the mob’s fever or swallow the propaganda that stokes it. They shun the herd’s groupthink, roll their eyes at party loyalty, and chase knowledge not for profit but for its own stubborn sake. Money, to them, is a tool, not a god. Beauty and goodness aren’t means to an end: they’re the end itself.

And the Remnant can read.

Nock’s Remnant aren’t just literate. Literacy is cheap. The masses can decode words and pass sentences through their skulls like ticker tape.

But reading? That’s reflection and wrestling with ideas till they yield something true, good, beautiful or mysterious, paradoxical, humbling.

Literacy’s a mixed bag, Nock warned. Mere literacy is a megaphone for mass manipulation, a tool for propagandists to herd the gullible. But true reading? That’s the spark of the Remnant . . . and almost certainly the spark of a healthy right hemisphere of our brains.

History’s blunt: only about 10% of any society bothers to be literate. The Western world changed that throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, achieving near universal literacy, even giving rise to a middle class that devoured books like today’s eco-politico elite devours underage children.

But now we’re sliding back to that grim 10% benchmark. Wessie du Toit, scribbling in First Things, says we’re losing “deep literacy”—Nock’s “reading”—fast. College professors are sounding alarms: their fresh-faced undergrads can’t get through the shortest of books. The vast bulk of us—90%?— are staring at screens, skimming snippets, and stripping down our synapses.

We—you and I—need to claw our way toward that 10%, to inch our way along the spectrum from “the masses” to “the Remnant,” from mere “literacy” to “reading.”

If enough of us do it, maybe by some miracle the Remnant, or at least those who are on the Remnant side of the spectrum, can swell to 25%, or hell, even 51%. Maybe we can even stave off the new Moloch of literacy: AI (which can’t even begin to read, in the Nockian sense, because it has no right hemisphere).

But don’t hold your breath. The world’s always been a mess of stragglers and a handful of strivers.

Fortunately, the world isn’t our job. Our job is simpler: just make dang sure we’re part of the Remnant and fix the only thing we can—ourselves. The rest can root through the dumpster of Tweets, texts, and digital twaddle. We can’t worry about them. We have enough work to do, just getting ourselves out of that dumpster.