A Pilgrimage to a Maine Island in the Footsteps of John Steinbeck

By Howard Fishman at the Washington Post

I found a large, black-and-white poster of John Steinbeck, advertising a Library of America collection of his work. I had no idea where this poster had come from or how long it had been there, but I had the feeling I’d stumbled upon a talisman. Impulsively, I tacked it up on my wall, right beside my writing desk. Steinbeck had been an early hero of mine, and I was now in the process of finishing my first book. It seemed right and even comforting to have him glowering down at me as I worked, challenging me to live up to the ideals he’d once modeled: simplicity, directness, an abiding love for humanity in all its imperfections.

I hadn’t thought about Steinbeck in decades, but as a young man I’d read all of his work, and now I pulled some of those dusty old friends from my bookshelves. Among them was “Travels With Charley in Search of America,” published in 1962 — a work of autofiction about the writer’s cross-country road trip in a camper, accompanied by his dog. As I started rereading, Steinbeck’s words resonated from the get-go. “I discovered that I did not know my own country,” he writes, outlining the reasons for his trip. On the road, Steinbeck despairs at the waste created by our compulsive consumerism and laments the way our natural environment is being slowly poisoned by plastics and refuse. “We have overcome all enemies but ourselves,” he writes. All of this seemed relevant today.

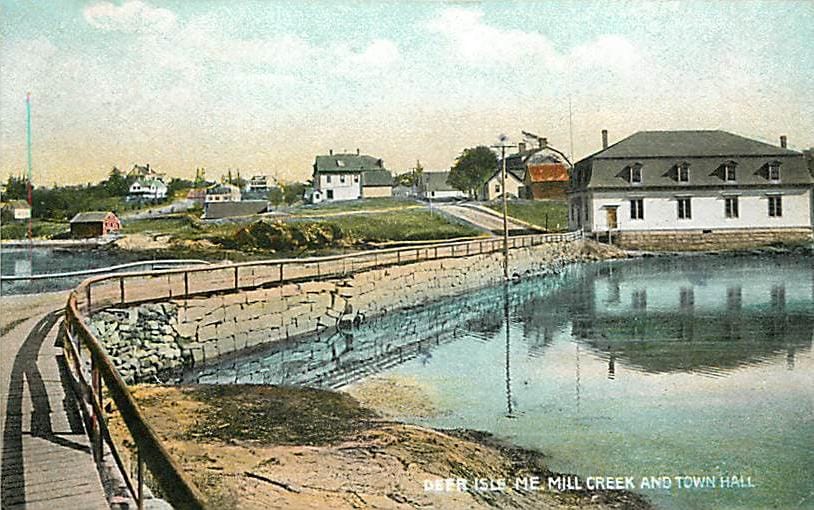

But the biggest early surprise for me was that Steinbeck’s first major stop on his trip was not someplace directly west of his then-home in Sag Harbor, N.Y., but way up on Deer Isle, Maine. That fact had vanished from my memory. He explains that his “friend and associate” Elizabeth Otis (actually his agent) was a longtime visitor there and had urged him to go: “When she speaks of it, she gets an other-world look in her eyes and becomes completely inarticulate. … All I knew about Deer Isle was that there was nothing you could say about it.”

After he’s been, he finds that he agrees with her assessment. “One doesn’t have to be sensitive to feel the strangeness of Deer Isle,” he writes, noting that the place “is like Avalon; it must disappear when you are not there.” Steinbeck had a lifelong obsession with Arthurian legend, so this was no casual reference. His book “The Acts of King Arthur and His Noble Knights” would be published posthumously in 1976, and Avalon is central to those stories — a magical island known for its healing powers, and the place where Arthur is taken after he is wounded in battle.

I wanted to see what, if any, part of Deer Isle remained from Steinbeck’s journey, though I knew I wouldn’t be the first writer to choose “Travels With Charley” as a departure point for exploration (nor even the first for The Washington Post; Rachel Dry did so in 2011, focusing on his stop in Fargo, N.D.). I, too, felt disconnected from my country. The idea of getting out to see a part I was unfamiliar with — especially one that had left Steinbeck flummoxed to describe to his satisfaction — compelled me to pack a bag.