A Forgotten Catholic Novelist

Stephen Schmalhofer at First Things

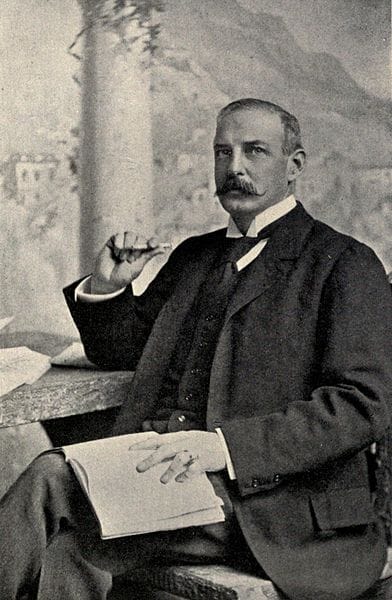

Although he is almost forgotten today, the Romantic novelist Francis Marion Crawford, a Catholic convert, outsold his friend Henry James in the early twentieth century. Undergraduates at the University of Notre Dame in the 1920s devoured his novels, ranking him alongside John Henry Newman and Robert Hugh Benson. Russell Kirk was his Romantic disciple, and he endorsed Crawford’s novels as “handsome approaches which we traverse by owl-light” in a “fresh search for the wondrous.”

His bestseller Saracinesca, soon to be available in a new edition from Cluny Media, is both art and artifact. Set in Rome, it holds in its pages the last echoes of the era when “Viva Garibaldi!” and “Viva Pio Nono!” rang out in rivalry on the streets of the Eternal City.

Elected in 1846, Pius IX had to make a quick study of politics as the great powers around the Papal States struggled to maintain the geopolitical order known as the Concert of Europe. When King Charles Albert of Sardinia-Piedmont declared war on Austria in 1848, the Romans used the crisis to demand a democratic ministry in the Papal States. Pius IX and his government were forced to flee, and General Giuseppe Garibaldi was given command over the defense of Rome. A French army, deployed by Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte, forced Garibaldi’s troops to withdraw, and Pius IX and his government was restored. This detente in the drive for Italian unification and liberalization is the setting for Saracinesca.

Crawford wrote Saracinesca with the authority of an eyewitness. Born in Italy to American parents in 1854, he was raised in Rome’s Villa Negroni. The Crawfords’ landlord was Prince Massimo, a member of the black nobility—those princely Roman families who remained loyal to the pope. It was a different time: “People crossed the Alps in carriages; the Suez Canal had not been opened; the first Atlantic cable was not laid; German unity had not been invented; Pius IX reigned in the Pontifical States.” Romantic relations between men and women were hemmed in by the social construction of formal courtship and the practical construction of Roman couture. To sin against chastity is practical only in thought, not in deed, “when a woman of most moderate dimensions occupied three or four square yards of space upon a ballroom floor.”

Saracinesca is the first novel in Crawford’s Roman tetralogy, followed by Sant’ Ilario, Don Orsino, and Corleone. It follows Giovanni Saracinesca, the only son and heir to the millennia-old Saracinesca titles and estates. Naturally, he is the most eligible bachelor in Rome. His father, Prince Saracinesca, belongs to “the old, patriarchal class, the still flourishing remnant of the last generation, who prided themselves upon good management, good morals, and ascetic living.” He prefers manly activity on his country estates to gossip in Rome. His son’s disinterest in marriage exasperates him: “Would you have Saracinesca sold, to be distributed piecemeal among a herd of dogs of starving relations you never heard of, merely because you are such a vagabond, such a Bohemian, such a breakneck, crazy good-for-nothing . . .?”