Hesychasm: The largely-forgotten literary tradition that takes Stoicism to the next level

I’ve long been a fan of the Stoics. Epictetus especially, but Marcus Aurelius’ Meditations and the works of Seneca have always held a sort of mesmerizing sway over me.

And, of course, Evagrius.

Who?

“Evagrius the Solitary” or “Evagrius of Pontus.” Sometimes spelled “Evagrios.”

He lived from 345 to 399. He wrote On Asceticism and Stillness.

I’m not sure there’s ever been a more Stoic-sounding title in the history of literature.

But though Stoicism has gained a lot of popularity thanks largely to the efforts of Ryan Holiday, Evagrius hasn’t, and neither has Evagrius’ literary tradition: Hesychasm.

The Sound of Silence

Stoicism is, at bottom, all about silencing the mind. Dispassion in the face of things that otherwise arouse passion. Resignation in the face of things that disappoint. Indifference in the face of things that raise emotions.

Mental silence. It’s a good trait, but human development didn’t stop with the death of Marcus Aurelius in 180 AD, and neither did the development of Stoicism.

Stoicism, you see, had a child.

And her name was “Hesychasm.”

Whereas Stoicism is all about quieting the mind, Hesychasm is, at bottom, all about quieting the heart.

A fourth century Hesychastic writer known to us only as the “Pseudo-Macarius” says of the heart:

The heart itself is but a small vessel, yet dragons are there, and there are also lions; there are poisonous beasts and all the treasures of evil. There also are rough and uneven roads; there are precipices. But there too is God, the angels, the life and the Kingdom, the light and the apostles, the heavenly cities and the treasures of grace — all things are there.

The parallels with Victor Hugo’s portrait of the soul 1,500 years later are vivid:

[T]here is one spectacle greater than the sky: That is the interior of the soul. There, beneath the external silence, giants are doing battle as in Homer, melees of dragons and hydras, and clouds of phantoms as in Milton, ghostly spirals as in Dante.

Heart, mind, and soul. They’re synonyms. Or maybe similar. Or maybe overlapping. Or maybe symbiotic.

It depends who you ask.

You find all three in the Hesychastic tradition, but “heart” takes center place.

Put a Little Love in Your Heart

Hesychasm picks up where Stoicism leaves off. Stoicism has long been known as the “porch” of Christianity. Greek stoa means porch, a location in Athens where the Stoic school first met in the 200s BC, but it also refers to Stoicism’s status as the last great philosophical school before the advent of Christianity and, therefore, the entry into Christianity.

Stoicism taught stillness of the mind, which is a great good. It helps to slow the reel of thoughts that plagues our every day existence. Stoicism in large measure eliminates the reel altogether.

But that creates a vacuum of sorts. The mind is active. It wants thoughts. Even in its highest form of spiritual development, it craves food.

Hesychasm understood this. It, like Stoicism, counseled quieting the mind, and prescribed meditation techniques to accomplish it, but Hesychasm also appreciated that, once the mind is still and empty, a vacuum exists that needs to be filled.

Hesychasm filled it with love.

In Hesychasm, Stoicism’s silence of the mind morphs into a loving stillness of the heart. It’s Stoicism on steroids.

When you quiet the mind/heart, in reality, you’re just quelling your ego. Let’s face it: Those thoughts that hurtle through your mind are almost always self-centered . . . about you: what you’re going to do, worries about what might happen to you, unkind thoughts about people who have harmed you, imaginations about what good or bad things might happen to you.

Etcetera and self-centered etcetera.

All ego all the time.

But when you practice Stoicism, the ego is shrunk. Starved of the thoughts that feed it, it starts to atrophy. Once it atrophies enough, something is ready to take its place.

That “something,” in the Hesychastic tradition, is love.

Love is affection, concern, attraction to Other. It is, by its nature, the opposite of ego and self-centeredness.

That’s why I say Hesychasm is Stoicism on steroids. It goes into the Stoic’s ego-shrunken mind and infuses it with love, the greatest thing of all . . . and turns it into the heart.

The Book of Love

So, yes, I suggest you may want to move beyond the Stoics and read the Hesychasts. If you want to start at Hesychasm’s beginning, try Benedicta Ward’s classic Sayings of the Desert Fathers. If you want to hear what the desert mothers said, try her Harlots of the Desert.

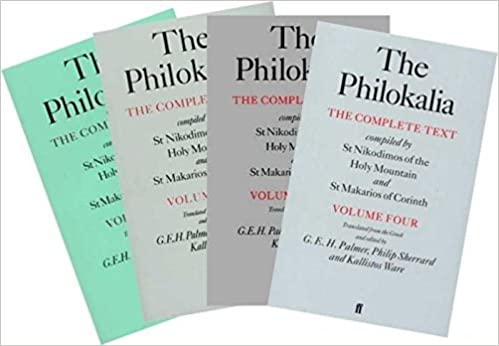

But if you want to jump into the Hesychastic literary tradition in its full flowering, dive into The Philokalia (Greek for “love of the beautiful”).

The Philokalia is a vast anthology of ascetic and mystical texts dating from the fourth to the fifteenth century. It was first published in Venice in 1782 by two leading eighteenth century spiritual lights, Macarius and Nicodemus of the Holy Mountain. Ukrainian-born Paisus Velichkovsky translated it into Slavonic and issued it under the title Dobrotolubiye (Slavonic for Philokalia), where it became a mainstay of Russian spirituality. Dostoyevsky read from it constantly, and it gave us the classic Russian tale, Way of the Pilgrim (which was central to J.D. Salinger’s Franny & Zooey).

Devil in Disguise

A word of caution: If you dive into The Philokalia, you will be reading Christian writers. In fact, they’re almost all monks, so you’re reading rigorous Christian writers, who were normally writing for rigorous Christian readers . . . other monks.

As a modern reader, you might find references to God/Jesus, devils, and prayer a distraction.

If so, a few simple suggestions:

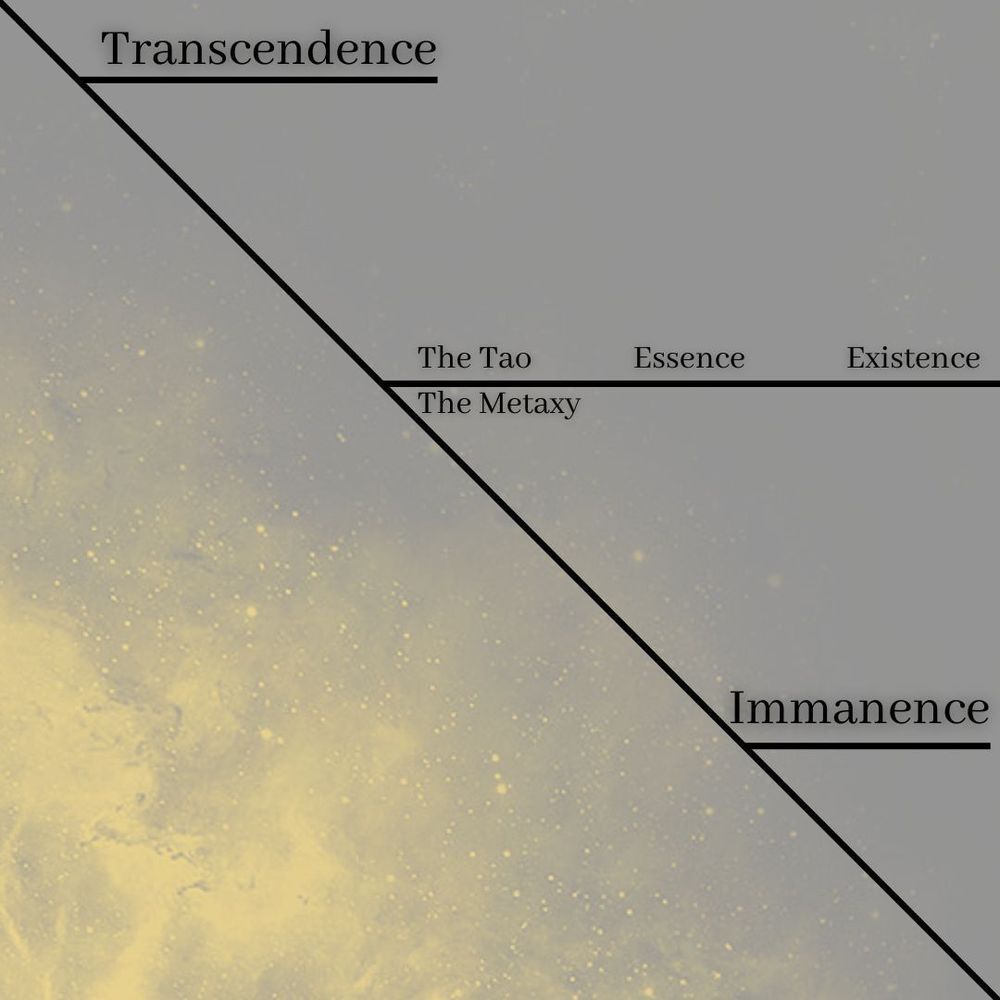

When you read “God/Jesus,” merely replace it with “Tao.” It’s an acceptable practice, as evidenced by C.S. Lewis’ The Abolition of Man’s endorsement of the Tao. If you’re acquainted with the Tao, the substitution will often resonate.

When you read “prayer,” just think “practice” or “meditation.” If you really need to situate yourself in our current cultural milieu, call it “mindfulness meditation.”

And most importantly, when you read counsels about the demons, merely replace the references with “thoughts.”

In the Hesychastic tradition, “demons” and “thoughts” tend to be synonymous. Demons are those forces that give us the thoughts that disrupt and disorder our hearts.

We enlightened moderns might scoff at the notion of demons, but if you really struggle with thoughts like these monks did, and fail repeatedly like these monks admit they did, those “thoughts” start feeling demonic. You start asking yourself, “Why can’t I stop these negative thoughts from running through my mind?”

For the monks in the Hesychastic tradition, modern psychology’s discovery of the negativity bias (negative thoughts are more powerful than positive ones, so we gravitate to them) couldn’t account for the sheer depth, complexity, and power of the relentless and negative thoughts painted by Victor Hugo in that quote above about the soul.

Only one thing could: demons.

In the pages of The Philokalia, the Hesychastic writers give volumes of advice for tackling them.

Those demons are alive and well in our modern/postmodern world. They’re just disguised better.

The Hesychastic monks will help you to start recognizing them in all their cunning depths.