Wednesday

Ride the Wave

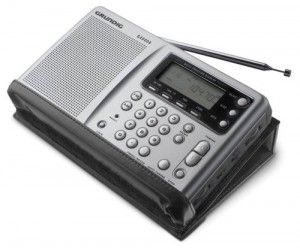

I came into an easy $80 a few weeks ago, so I splurged on something that has long intrigued me: a shortwave radio. I bought a Grundig G4000A. The model was recommended by a "survivalist" blogger as a solid less-expensive radio, and the Amazon reviews were good. Shortwave radios are a rage with the Armageddon types, and that appealed to me, and Peter Schiff got his start on shortwave. I'm also intrigued by the possibility of enhanced AM reception and listening to off-beat radio broadcasts from around the world. There's something about tuning in broadcasts from one's backyard instead of listening through your computer speakers. It's a tactile experience, as Polanyi or McLuhan might express it, or as Taleb captures it in this aphorism: "They read Gibbon's Decline and Fall on an eReader but refuse to drink Chateau Lynch-Bages in a Styrofoam cup." But the real reason I bought the radio: I've wanted one since I was a kid. A year ago, I mentioned that I really enjoyed late night radio as a kid. The lure of such radio broadcasts has lessened now that my available time has evaporated, but the enjoyment is still there. I'm hoping this shortwave radio will introduce me to a new entertainment world of off-beat stuff that would otherwise escape my notice. If you have any shortwave recommendations, please pass them along. I know virtually nothing about the medium. * * * * * * * Podcasts Still Going Strong. I'm not sure when I'll have time to listen to shortwave broadcasts. My podcast universe is filling up with more and more quality shows, and my customary shows continue to plug along. This week, Econtalk is running a delightful interview with George Will. I'm only about 25 minutes into it, but so far it's great. I'm looking forward to listening to the rest on my walk to work this morning. * * * * * * * Will, Obama, and Railing. Will, I learned on the podcast, is the most-voluminous writer in the history of Newsweek (78 years). This week's column is worth checking out: High Speed to Insolvency: Why liberals love trains. Will asks why Obama and other liberals are pushing for a high-speed rail system at a cost of billions, when the deficit obviously can't tolerate it. He offers the following theory: "The real reason for progressives' passion for trains is their goal of diminishing Americans' individualism in order to make them more amenable to collectivism. To progressives, the best thing about railroads is that people riding them are not in automobiles, which are subversive of the deference on which progressivism depends. Automobiles go hither and yon, wherever and whenever the driver desires, without timetables. Automobiles encourage people to think they–unsupervised, untutored, and unscripted–are masters of their fates." It's not a bad theory, but I suspect there's more to it. I can think of three other explanations off the top of my blogging head: high-speed rail would help reconnect and revitalize the inner-cities, where progressives' constituents dwell; environmentalism; and the simple lust for progress, whatever the stripe. But Will couldn't address all those reasons in an op-ed piece, and he's hardly trained to do so anymore. During the podcast, he half-jokingly said that his decades of opinion writing causes him to "think in 750-word chunks."