From the Notebooks

The Hack

Most men are hacks. I think that's a fair statement. And I suspect most men fall into the category of “hacks.” Mr. X is a hack at this and that and the other thing. He does a lot of things kind of well, but nothing great.

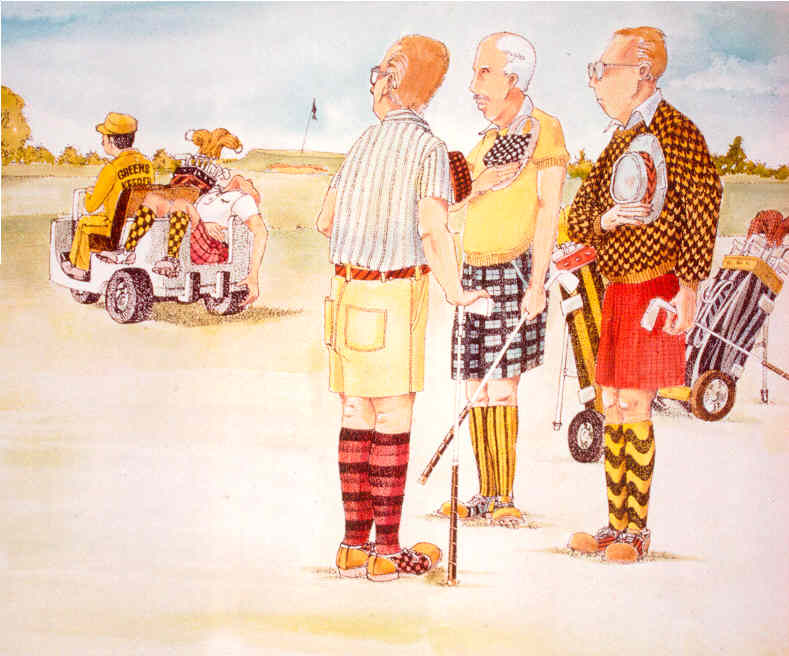

Consider the typical person. We'll call him “Mr. Hack.” Mr. Hack plays golf and has a 15 handicap, which would make him respectable at most golf clubs, but a dozen-plus strokes behind pro level. He has net assets in excess of $500,000, which puts him in the upper-middle class, but well below the Forbes Top 100. He keeps himself in shape and well-groomed, but he ain't Tom Cruise. He keeps abreast of current affairs, but he's ignorant compared to the likes of George Stephanapolous. He can write a coherent memo or maybe a competent short story, but he falls well below a Pulitzer nominee. Maybe he studies a particular area–American history, the Bible, scientific discoveries–but he knows very little next to the professor in those areas.

There's nothing wrong with this, except one: Mr. Hack would like to exceed in all those areas that interest him.

Mr. Hack wants the swing of Tiger Woods, the money of a tycoon, the body of a movie star, the knowledge of a statesman or professor, the prose of Steinbeck. Yet in all these areas–areas he cares about–he falls short. He doesn't reach the standard of excellence in any of them.

Why?

I'm reminded of a great pianist who was approached by a gushing admirer after a concert. She said to the man, “I'd give my life to play like you.” The pianist responded to her, “I did.”

Unlike that great pianist, Mr. Hack doesn't give his life for any of the things that interest him. There, I believe, rests part of the answer.

But that's just the surface answer. Subsequent “why's” follow: Why don't people give their lives for what they care about? Why are their interests so scattered? Why don't people catch fire with an area (why can't many writers, for instance, follow-through with a book idea?). And even if a person could focus on just one interest, would he also have to sacrifice those other things that make life precious, like religion and family and enjoying the outdoors? And if Mr. Hack is normal–and the observations gleaned during 40 years of living have convinced me that he is–what does that say about the person who is not a hack? Is a freak, and if so, a good freak or a bad freak? I'm also curious to know what a hack can do to excel in one area: can a middle-aged hack jettison the myriad of interests and focus on one and succeed? For that matter, should he? Perhaps “hackedness” is our natural calling that ought not be disdained, even though people, at least us Americans, have a mental habit of doing so.