Feature Essay

Slowly Learning to Live

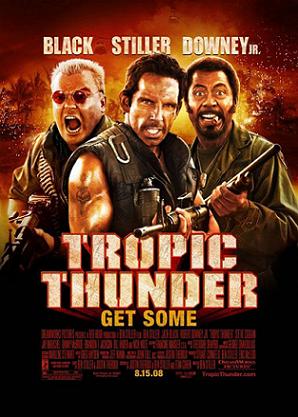

I'm not looking to join last summer's Tropic Thunder velitation, but about ten years ago I volunteered to sell Tootsie Rolls to help people with mental disabilities. I figured it was an easy way to do some good, so I stood on the steps of my church as people came out of Mass and enthused, “Help the retards! Buy a Tootsie Roll. Only a buck. Help the retards!”

The next day, I thought about the funny look on parishioners' faces. I asked my law partner: “Your sister has Down's Syndrome. Is it offensive to refer to such people as 'retards'? Because I was at church yesterday . . .”.

He stared (okay, glared) at me and said, yes, it was highly offensive and that I'd probably cost the firm a dozen clients. He also said something to imply that I was a slow learner.

It's not the first time I felt like a slow learner. I'd been at politically-correct institutions of higher learning for five years before I learned that David Allan Coe's hugely-incorrect Underground Album isn't proper casual listening with people you've just met.

There's also a litany of weightier things that I haven't penetrated facilely. I read Hayek's Road to Serfdom at age 16, but am still learning its lessons. I started reading Chesterton at age 20 and even edited Gilbert Magazine for a short spell, but I'm still a bit cloudy on the whole distributism thing. At age 24, I remember sitting down on a stairwell bench at Notre Dame Law School to ponder the idea that actual sin hinders spiritual development (something not emphasized in my Lutheran upbringing–Luther said my soul is snow-covered dung–but still one that I should've intuited earlier).

It's kind of discouraging.

Czeslaw Milosz helped me out a few months ago with this aphorism: “[T]he science of life depends on the gradual discovery of fundamental truths.”

A fundamental truth that I didn't fully absorb until my late thirties is that every pursuit has an opportunity cost. I understood the concept, of course. I understood that time, like money, is spent and once spent can't be spent on something else. But I didn't fully absorb it.

Once I started to appreciate fully the implications of the opportunity cost of time, things changed for me. I wrote less and spent more time with beer. I read less and spent more time with my children.

I still read a lot, but when I get ready to start reading something, I take a hard look at it first and ask myself questions: “Do I really need an answer to Elvis, What Happened? Do I need to understand Sun-tzu's The Art of War (given the Chinese Olympic medal count, maybe I do)? Why exactly am I reading De Quincey's Confessions of an English Opium-Eater?

My new appreciation for the opportunity cost of time has also made me more understanding of people who “waste” their time. Gone are my days of railing against golfers, fishers, hunters, Bridgers, NASCAR fans (I still indulge that one a bit), lawn care nuts, and craft fair patrons.

Who am I to judge how others spend their time? In this, I've become as morally relativistic as Jane Fonda in Hanoi.

Still, it helps to have objective standards, and some of the best are the Platonic transcendentals: the Beautiful, the Good, and the True.

The thing to understand about the transcendentals is that they are things we pursue for their own sakes. They aren't means to other ends. We don't play frisbee because it makes us cool, and we don't read because chicks dig it. Reading and playing are ends in themselves.

Not everything we do for itself is transcendental. Smoking dope and cavorting with hookers aren't done for anything but the fun of it, but they're hardly transcendental pursuits.

But if a thing is not immoral and it's a thing done for itself, you're probably dealing with a transcendental. Plato observed that we “should spend one's days playing at certain games–sacrificing, singing, and dancing.” He also approved of philosophizing and conversation. Such things are lofty because they're not done for the sake of anything else. If a person fills his earthly plate with such things, he can't go too wrong.

You can't exactly preach the transcendentals in today's Harold and Kumar market place of ideas, of course. “Beautiful” has come to mean “do-able,” “good” is what gives you a rush, and “true” is Pontius laughable.

If you want to talk about the three transcendentals, try some contemporary catchwords. Instead of “beautiful,” emphasize “inspired.” Instead of “good” and “true,” try insipidities like “volunteerism” and “self-improvement.” People might buy into them.

And if they buy into them, you can subtly suggest that time is limited and there's an opportunity cost to all activities. You might even suggest that the science of life is more like an art, an art that ought to be developed. Even if the development is often slow.