We Need to Resist the World of Pure Action

Last week, Michael Osterholm went on the Joe Rogan Experience for the second time.

Osterholm, some might recall, went on Rogan early in the pandemic. Later Rogan guests decried him as a “chicken little” who was just trying to hawk his book. Osterholm said things that turned out to be wrong (e.g., he said COVID wouldn’t go away with warmer weather). In the COVID wars, he was on the Left.

But he went on Rogan last week and almost immediately said that the pandemic, nearly two years later, has taught him the importance of humility.

I didn’t listen to the rest of the podcast (I’m COVIDed out, to be honest), but I was impressed by the acknowledgment.

I don’t think I need to review all the problems associated with lockdowns. Alcohol abuse, mental illness, domestic violence, and obesity increased significantly. Small businesses died. Economic inequality skyrocketed, as big businesses and Wall Street gleaned profits from the lockdowns while the world’s poor suffered the most. People died because they couldn’t get their customary medical care (like my young diabetic cousin who couldn’t get his insulin pump calibrated and died of a heart attack). The lockdowns were such a debacle that the Biden administration is now saying they were a Trump-era thing, notwithstanding that the administration’s blue fellow-travelers locked down far more fiercely than their red opponents.

That’s what a debacle the lockdowns were.

But at the time, they seemed to make sense. I supported the first wave of lockdowns to flatten the curve.

There was that human urge: We have to do something! It’s an urge, de Tocqueville observed in Democracy in America, that is especially prevalent in America.

We are a culture of pure action.

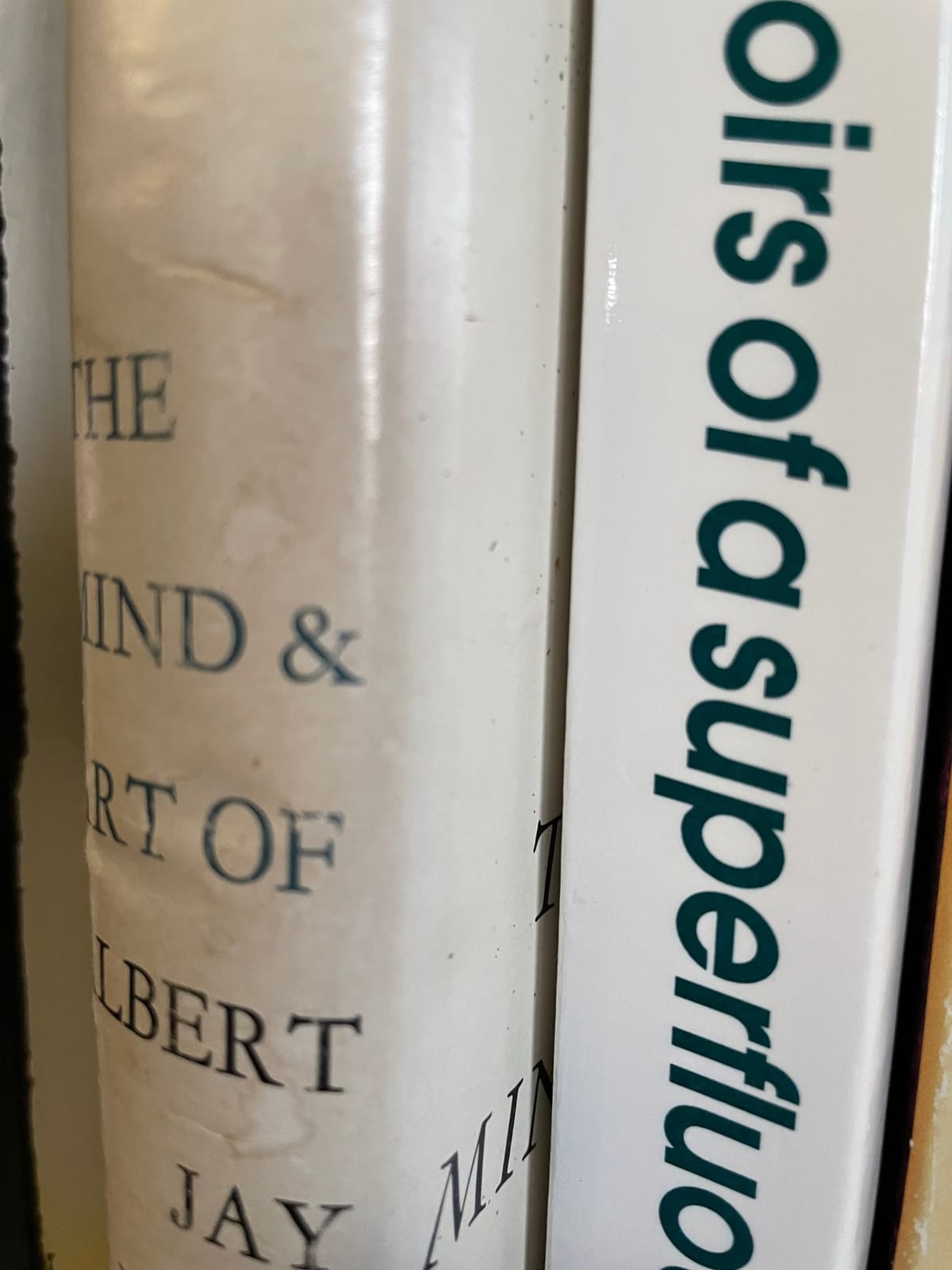

Albert Jay Nock wrote an essay that has become a classic: “Snoring as a Fine Art,” in which he recounts the great success of the Russian General Kutusov against Napoleon. Kutusov beat by Napoleon by . . . doing nothing. He fell asleep and snored loudly during important meetings. He didn’t act when people thought he should act. He screwed around on personal interests when he should’ve been working.

And he beat Napoleon.

In War and Peace, Tolstoy says Kutusov knew there is “something stronger and more important than his will” so he could “abstain from meddling, from following his own will and aiming at something else.” Nock said Kutusov did everything he could to “keep his consciousness from playing upon the sequence of events which he alone knew was going to take place.”

When it comes to public policy, the first response of our leaders should not be to act.

I know: My assertion runs 100% contrary to everyone’s immediate reaction, but I stand by it. There are many good reasons to abstain from acting, including the unintentional consequences and the limits of knowledge and acting with those limits.

But there’s more.

The world of action is one of subject-object. I, the subject, act on X, the object. Every action of the politician exists in the world of subject-object. It’s unavoidable.

What if reality is more than subject-object? What if there is a gap between subject-object that we bypass and don’t notice when we’re caught up in the frenzied world of action, one that can only be contacted by setting aside one’s ego (the subject) and one’s consciousness (another subject) and its goals (the object) and plans (another object)?

And what if there is an area of existence that stands wholly outside the reality of essence and existence (or “accidents” and “substance,” is how the classicists might put it), one that is wholly detached from our world of grasping and knowledge and even language?

If there is that area of reality, a lot can be gained by getting in touch with it. What, exactly, can be gained? I can’t say for sure. If I could, it wouldn’t be the area of reality that I’m talking about here, since this area transcends language. Philosophers have referred to it as the “act of existence.” Taoism calls it “the Tao.” Zen says it’s the first principle of Zen.

If there is such an area, we lose something when we act without spending a lot of time getting in touch with it. We lose something when we live solely in the world of pure action.