Neil Young Never Hated the Man

He just hated THAT man

“Their job is to push back against the Man and Neil Young should know the Man isn’t Joe Rogan . . . [Y]ou’re an old rocker, you’re supposed to push back against the Man – Joe Rogan is pushing back against the Man and you’re pushing back against Joe Rogan.” Adam Carolla, speaking on Hannity

A Tale of Two Lefties

The Neil Young-Joe Rogan kerfuffle brought an embarrassing truth about the Left to the surface of our culture’s consciousness: the Left has always been polarized within itself.

For too long, we’ve thought of the 1960s as a monolithic revolution against “the Man.” Hippies hated the Man; Timothy Leary and the acid movement hated the Man; revolutionary groups like Students for a Democratic Society hated the Man; rockers hated the Man; black militants hated the Man; feminists definitely hated the Man.

That’s all true.

But there’s a huge difference in their hate.

Some 1960s Leftists hated the Man because they wanted peace and love. They wanted to live unmolested by the Man: simply to be left alone in their pursuits. Those are the old hippies who now live hard but simple lives off the grid and populate northern California, some growing great weed. Think Bob Dylan and Jack Kerouac.

On the other side of the 1960s Leftist spectrum, Leftists hated the Man because they wanted to be the Man themselves. They never really hated the Man. They hated that Man: the Man that wasn’t them. Those are the student revolutionaries who later moved into conventional politics and university positions where they influence public policy. Think Tom Hayden and Bernardine Dohrn.

The Leftists who hated the Man grow great weed for reasonable prices, but the Leftists who hated that Man control the culture.

Neil Young was a slash-against-the-Establishment rocker in the early 1970s, but he never hated the Man. He hated that Man, so when comedian Adam Carolla went on Hannity and inveighed against Neil Young, he got the noun correct but botched the adjective.

Proudhon

“Anarchy is Order.” “God is Evil.”

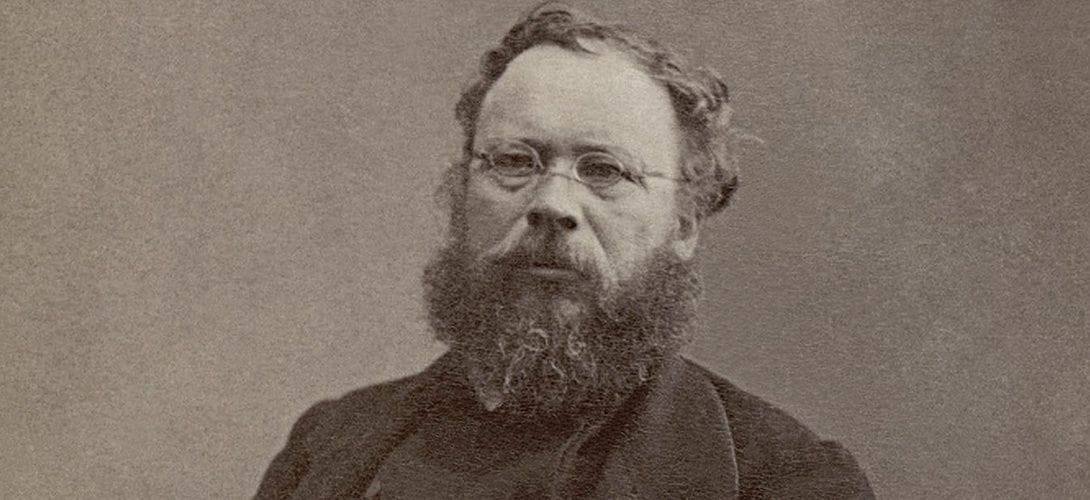

Those are Proudhonism. As in “Pierre-Joseph Proudhon” (1809-1865), the first self-styled anarchist. He was provocative and is considered one of the most contradictory thinkers in the history of political thought. He didn’t try to come up with a systematic theory and didn’t care much if he wasn’t always consistent. He was, in a sense, a metaphorical bomb-throwing anarchist: tossing bombs of passionate thoughts that were designed to obliterate targets, but due to their explosive quality, took out other things in the process.

Proudhon’s campaign was, in the words of anarchist historian James Joll, “a relentless critic of the whole of existing society.” He railed against private property; he advocated small communities with women in the home. He didn’t like Jews, homosexuals, or the English. If there were intellectuals he disagreed with, he went about dismantling their ideas.

One of those thinkers was the German thinker Ludwig Feuerbach (1804-1872), whose atheistic thought swept mid-nineteenth century western Europe’s intellectual and radical circles. But it didn’t sweep away Proudhon. Proudhon, an atheist like Feuerbach, said Feuerbach wasn’t denying God: he was merely flipping God upside-down.

Proudhon and Feuerbach

Feuerbach’s central idea is “alienation.”

According to Feuerbach, religion is merely an assignment of our best qualities to God. By projecting our best qualities into the transcendental, we “alienate” ourselves: we surrender our best qualities to God, who, in turn, is just a fictional construct (the being that embodies our best qualities).

If the concept of God is destroyed, Feuerbach taught, we can take these best qualities back for ourselves, end the alienation of our great qualities, and bring them to bear on immanent things, thereby triggering the great turning point in history and ushering in a new humanism.

Proudhon wasn’t having it.

Feuerbach and his disciples, Proudhon said, didn’t want to kill God; they wanted to appropriate from God and thereby set society up as an alternative to God . . . but it was still all God, all the time. By setting themselves against God, Proudhon saw, they still believed in God. If he were speaking in the postmodern deconstructionist tradition of Jacques Derrida, Proudhon might have said the Feuerbachians, while claiming to be killing the logos, were merely fabricating more logos (logocentric ideas).

Proudhon and Marx

Marx adored Feuerbach. He considered him a veritable second Luther on the road to human emancipation.

Marx wanted to be the third Luther, a Feuerbach on steroids.

Marx took Feuerbach’s idea of spiritual alienation and came up with the idea of economic alienation and its intertwined twin, social alienation. In the Marxist worldview, “alienation” is always the ultimate bugbear.

“Just as in religion man is governed by the products of his own brain, in [capitalism] he is dominated by the products of his own hands” That’s Marx’s view of the working man’s economic alienation: he makes things for someone else who owns them, who then uses them to further enslave the men who made them in the first place. That is the core of economic alienation.

Just as the notion that God exists results in men alienating their best qualities to Him, Marx taught, capitalism results in men alienating themselves from their labor. They don’t get to enjoy the fruits of their work. It’s economic self-alienation, which then works its way through the superstructure of everything else (politics, society, life), making alienation the norm in capitalist societies.

Alienation, Marx taught, must end. Whether it’s Feuerbach’s religious alienation or economic alienation which then brings social alienation, it must stop. That is what the Communist paradise would do. By establishing a world with no private property rights or God, all alienation would end. Man would become whole. A paradise would ensue.

Proudhon didn’t buy it. He saw that Feuerbach was merely replacing God with another god and that Marx was merely replacing one logocentric idea with another.

Marx and Proudhon, both Leftists, got along when they first met and then corresponded for awhile, but the correspondence ended when Proudhon sent a letter to Marx that strongly objected to any system that would fabricate more logocentric ideas (which Proudhon called “a priori dogmas”). This excerpt from that final letter is startling in light of today’s turmoil:

[F]or God’s sake, when we have demolished all a priori dogmas, do not let us think of indoctrinating the people in our turn … Let us have a good and honest polemic. Let us set the world an example of wise and farsighted tolerance, but simply because we are leaders of a movement let us not instigate a new intolerance. Let us not set ourselves up as the apostles of a new religion, even if it be the religion of logic or reason.

Marx seethed. He never responded. He had no further use for Proudhon and ignored him, except when Proudhon published something, which would prompt Marx to savage the writings and call Proudhon a “petty bourgeois.”

Feuerbach, Marx, and Young

Feuerbach wanted to replace God with another god.

Marx wanted to replace one logocentric idea with another.

The 1960s-1970s Neil Youngs of the world wanted to replace the Man with a different Man.

The Neil Youngs of the world won. And now they want their Man to stay on top, and they’ll do whatever it takes to make sure He does.

If the history of secular humanism in the 20th century is any indication, I’m afraid viewpoint intolerance, canceling, and deplatforming are modest measures for such people. They are, after all, defending their Man and their ideas.

They are defending their god.