How to Break a Maniac

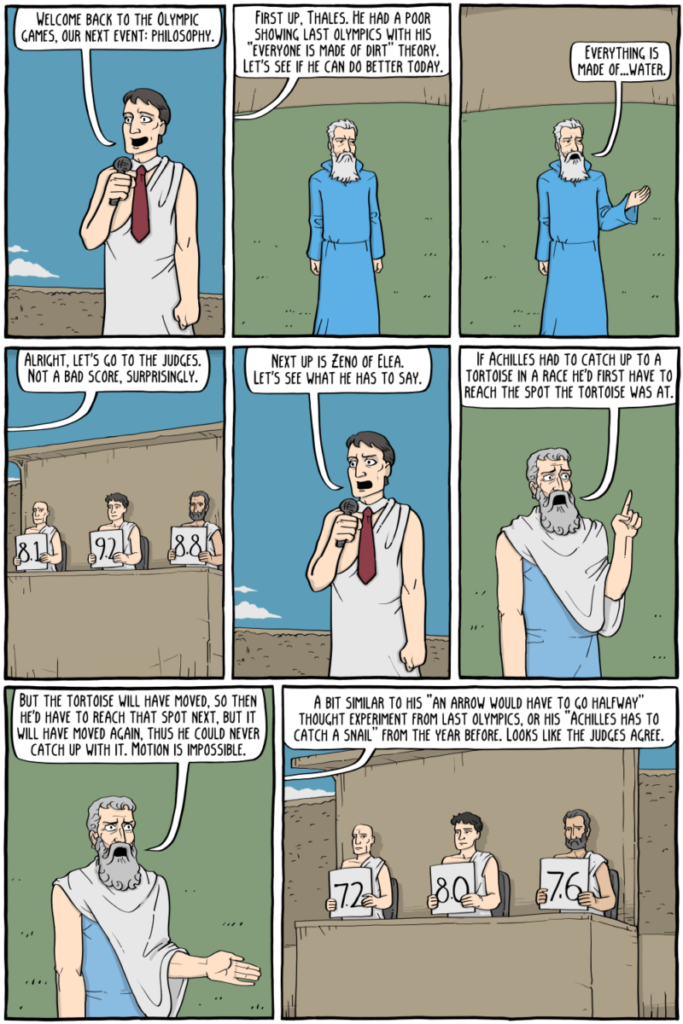

My daughter sent that comic to me. The whole thing shows three ancient philosophers competing in the Philosophy event at the Greek Olympics: Thales, who declares everything is water. Zeno, who declares motion is impossible. Socrates, who declares they’re full of bulls***.

Socrates won.

But of course, he didn’t really win: he refuted nothing.

His refutation was even worse than Samuel Johnson’s stone-kicking “refutation” of George Berkeley.

It’s a well-worn anecdote: Samuel Johnson and his companion, James Boswell, stood outside church in 1763, talking about George Berkeley’s startling philosophical conclusion that matter doesn’t exist.

Here’s how it works: We only perceive matter’s characteristics. That green thing has four legs, a flat surface, and a horizontal surface. Our mind then combines those things to declare “chair.” But we don’t perceive chair. We only perceive the things that comprise the chair and, therefore, the chair itself doesn’t really exist. Since all things are mere combinations of other things that we perceive in their relation to other things, nothing really exists. Everything is just our ideas. All is mind. There is no matter.

Boswell said, though it can’t be true, it’s impossible to refute.

“Johnson,” Boswell wrote in his famous biography, “answered, striking his foot with mighty force against a large stone . . . ‘I refute it thus.’”

That ended the discussion, but Boswell concluded the story by noting that he would’ve loved to have seen a genius like Johnson contend with Berkeley since Berkeley’s ideas could not be “answered by pure reasoning.” David Hume reached a similar conclusion about Berkeley’s ideas: “they admit of no answer and produce no conviction.”

They cannot be answered by pure reasoning

Zeno: There is no motion. Berkeley: There is no matter. We could add a few other philosophers into this tradition: Parmenides: There is no change. Derrida: There is no reality.

None of them could be refuted but none of them convinced anyone with a shred of ingenuousness or common sense. They probably didn’t even believe their own conclusions, and I can guaran-freakin’-tee to you that they didn’t live by their own conclusions.

But they couldn’t be refuted.

Why?

I think that lecher (and tosspot) Boswell hit on the answer: they could not “be answered by pure reasoning.”

There is something about reality that transcends reason: something not subject to reason, something that can’t be defined, something that defies capture by words.

Enter the realm beyond language and reason

This piece is a follow-up of sorts to last week’s post: “Are You Engaged in the Act of Existence? Then You’re a Man of the Tao.”

The “Act of Existence,” I pointed out last week, is prior to all else. The Act of Existence is prior to essence and attributes, which are prior to existence itself. Because the Act of Existence is prior to all else, it informs all else.

Importantly, all else doesn’t inform it. The part doesn’t capture the whole, the son doesn’t define the father.

So the world of essence and existence isn’t going to define the Act of Existence.

Words and reason are the tools of the world of essence. Essence is prior to existence, so essence’s tools paint existence as well.

But the Act of Existence is prior to it all.

That’s how Berkeley and Zeno and Derrida can be 100% logical and 100% wrong at the same time.

Ah, a paradox! Now we’re getting someplace

It’s a paradox.

Get used to it.

Everything informed by reality (the “Reality Spectrum,” I called it last week) is a paradox. I remember listening to an interview with Iain McGilchrist last year. He was describing a roundtable discussion with other heavyweight intellectuals that hit upon two contradictory statements that were both true. One of the participants lit up and said, “Ah, a paradox! Now we’re getting someplace.”

Exactly.

The Reality Spectrum is someplace. It’s everyplace. If you deny it, you’ll never get anyplace. You’ll reach conclusions: but nothing will be concluded. You’ll be right: but you’ll be wrong.

If you deny the Reality Spectrum, you’re playing poker without the face cards. You might draw a straight flush, 6 through 10, and reach for the pot, then the other guy will lay down four kings. You’ll see that you lost, but you won’t understand why. The full deck of the Reality Spectrum transcends your partial deck of essence/existence only. The partial deck can win hands, but in the long game, the full deck will win.

Maniacs are commonly great reasoners

In Chapter II of his classic book, Orthodoxy, G.K Chesterton describes “the maniac.”

“Maniacs,” GKC observed, “are commonly great reasoners.”

But they’re still maniacs because they reason within a very closed circle.

"The maniac’s explanation of a thing is always complete, and often in a purely rational sense satisfactory."

If the maniac says six guys have a conspiracy against him, then you tell him, “I spoke to each one of them. They assure me they don’t,” the maniac says, “That’s what conspirators would say.”

And he’d be right.

The argument itself can’t be broken. In order to get anywhere with the maniac, you have to break open his little world.

For the maniac who relies solely on reason, you have to break open his reality of essence-->existence only. You have to get him to see the Act of Existence: the Tao. You need to get him on the Reality Spectrum.

But you can’t use reason to do it.

Something else is needed.

It’s sometimes humor. When you juxtapose something next to the maniac’s stilted reality that he didn’t expect, he might laugh and inadvertently let in more reality.

But sometimes something harsher is needed. A jolt of sorts. Maybe a near-death experience. Maybe the birth of a child.

Or maybe someone wise just telling him he's full of bulls*** and kicking a rock at him.

Photo by Thiébaud Faix on Unsplash