I’ve Grown to Like Reprobate Leftists

I fear I picked up a lazy and stultifying mental habit in my early adult years: I habitually assumed every academic and artistic person is a reprobate leftist.

Well, not really, but I don’t think there are as many of them as I once assumed

I fear I picked up a lazy and stultifying mental habit in my early adult years: I habitually assumed every academic and artistic person is a reprobate leftist.

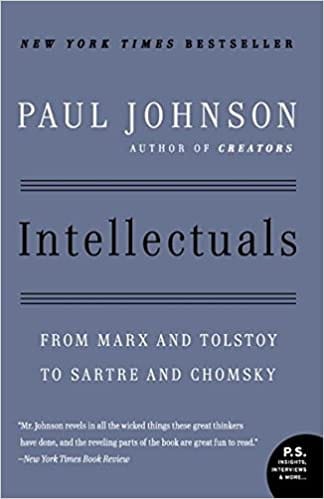

It was a habit largely inculcated in me by Paul Johnson’s Intellectuals, but there were other things. William F. Buckley’s observation that he’d rather be governed by the first 2,000 people in the Manhattan phone book than the faculty of Harvard. The degenerate leftism that largely was French intellectual life after World War II. Alfred Kinsey.

Sure, I made exceptions all the time, once I was shown that Mr. X was a solid family man or Ms. Y actually entertained a few right-leaning sensibilities or was a fairly serious Catholic. But I always had that assumption, which made me avoid them—their articles, their interviews, their ideas—in general.

Life’s short. Why waste time on reprobate leftists?

My subscription to The New Criterion has challenged that habit and, hopefully, killed it. Every month, I open it and see essays, reviews, and mini-biographies about people over the past 30 years that I’d never even heard of, probably because I’ve been in the crucible of child-rearing, with the resulting lack of reading time, sifted through the lens assumption of reprobate leftism.

I occasionally discover that the academics and artists whose work I intuitively ignored were neither leftists nor reprobates. Often, I find that people who were, indeed, leftists but not reprobates. Sometimes, I discover folks who were reprobates but not leftists.

Occasionally, I discover someone who is simply interesting, whether in his flawed biography or his work, but I have no idea whether he’s left, right, saint, or sinner.

That last category fits the last essay in the January 2022 issue: “The man who laughed in church.” It’s about the art critic, David Hickey, who said, “I do not want to be fair. I want the art I hate to go away. . . . I am not in favor of art—I’m in favor of the art I like.”

The essay opened with that quote. I was hooked immediately. I wasn’t disappointed by the rest of the essay. If you can access it (my subscription comes with online access; not sure what the unwashed shmoes can get), it’s worth reading.

A few excerpts:

Writing about Hickey’s appearance on Firing Line, during an interview with Tom Wolfe:

His outfit consisted of worn indigo jeans, polished black leather boots, and a tailored dove-gray jacket paired with a stylish black collar shirt. This sartorial choice, whether deliberate or subconscious, was Hickey’s way of straddling the fence dividing elite public intellectuals such as Buckley and Wolfe and the SoHo bohemians whom he had joined a decade and a half earlier after leaving his native Texas.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=m5NBoe5qHRE The Firing Line interview (go to minute 48:10 to hear Hickey . . . parental caution advised; Hickey is smoking (snicker))

Writing about Hickey when he became famous:

[I]t was his second nonfiction book, titled Air Guitar: Essays on Art and Democracy (Art Issues, 1997), that made him one of the most recognizable names of the art scene in the Nineties and Aughts. He had already been writing for publications including Artforum, ARTNews, the London Review of Books, Rolling Stone, and Art in America, where he served as an executive editor until, according to Dave, he was sacked for doing lines of cocaine on his desk. (He claimed that his employer objected not to the cocaine but to the scratches on the furniture.) Air Guitar, which he once referred to as “a very serious critique of abjection and institutional cowardice,” went through multiple reprints, and became popular enough to generate its own question on Jeopardy.

And finally, explaining why Hickey matters:

The author, Daniel Oppenheimer, makes a solid case for why we need to read and reread Hickey now: not only did he produce some of the best English-language essays on art and culture of the last century, but in our times those writings have proved themselves more prescient than ever. In the canonical The Invisible Dragon: Four Essays on Beauty (Art Issues Press, 1993), Hickey outlined how the “new puritans” from the progressive Left took over and transformed the new “therapeutic institutions”—museums, art schools, and fund-granting bodies.